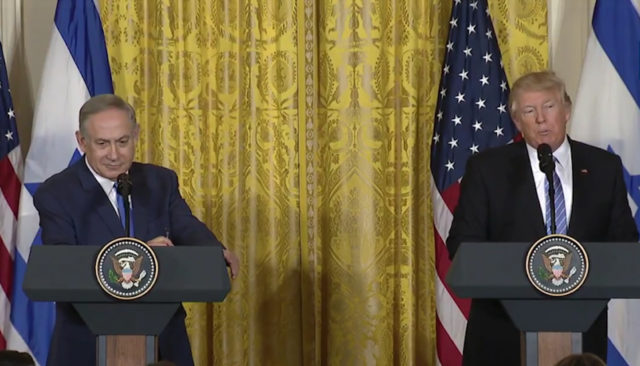

The optics, certainly, were fine. It was good to see an American president and an Israeli prime minister standing together on the podium with what appeared to be genuine good will. Most important, and promising for the future, perhaps, was how they dealt with the “two state solution” mantra. There was, for the first time in years, nuance in both the American and the Israeli position toward what has become a slogan without meaning.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reiterated the possibility of two states with caveats he noted:

• Palestinian acceptance of the legitimacy of Jewish sovereignty, echoing the words of the UN Partition Plan for Palestine for “a Jewish state.”

• Israeli security control from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River. “Israel must retain the overriding security control over the entire area west of the Jordan River. Because… otherwise we’ll get another radical Islamic terrorist state in the Palestinian areas exploding the peace, exploding the Middle East.”

President Donald Trump deferred, as befits someone who won’t live with the consequences of actions taken 6,000 miles away:

“I like the (solution) that both parties like… I can live with either one. I thought for a while that two states looked like it may be the easier of the two. To be honest, if Bibi and the Palestinians, if Israel and the Palestinians are happy, I’m happy with the one they like the best.”

Between them, it was clear that the door has been opened to other possibilities. There were references to meetings (present and possibly future) with Sunni Arab states that are increasingly willing to be seen in Israel’s company.

It should be noted here that Qatar’s representative in Gaza said last week that he had “excellent relations” with a number of Israeli officials. He told the Times of Israel that the Palestinian Authority (PA) was “standing in the way of solutions to the power shortages and other problems” in Gaza. “I am in contact with senior Israeli officials and agencies and the relationship is great,” said Muhammad al-Amadi.

It is still true that Qatar funds a variety of jihadist movements and has been Hamas’s primary funder. But the U.S. Treasury Department praised Qatar for moves to deny jihadists access to funds, and Qatar’s patronage may decline further with the secret-ballot election of Iranian ally Yahye Sinwar to head the organization in Gaza. Trading Qatar for Iran in Gaza is not a plus for Israel, but it may benefit Israel’s Gulf State relations.

Saudi relations with Israel are an open secret — they use third parties to import Israeli high-tech and water technology. Israel has had a diplomatic mission in Abu Dhabi since 2015. Through similar cutouts, Israel has sold defense equipment to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Relations with Egypt, particularly on security, are close and growing. Israel’s relations with Jordan have been key to Hashemite monarchy’s survival — and the monarch knows it.

None of this should be taken as a sign that Israel is anyone’s long-term friend or partner, but the opening for conversation other than “two states” is there. Where might that conversation go?

Back, perhaps, to the future.

What is commonly called the “Palestinian-Israeli conflict” is, in fact, the “Arab-Israel conflict.” The Arab states rejected Israel’s independence in 1948 and made war against it multiple times. UN Resolution 242 was designed to provide Israel with the security and legitimacy it had been denied by its accepting Israel’s control of territory beyond the 1949 Armistice Line until the Arabs came forward. Demonstrable Arab acceptance of UN Resolution 242 would pave the way for the “secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force” to which Israel is entitled.

It would also pave the way for a return to the 1993 Oslo Accords, which made no mention of statehood for the Palestinians, but which envisioned a “permanent settlement based on Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338.”

Jordan illegally annexed the West Bank in 1950, and from that time Palestinian nationalism has been deadly for the Kingdom. The 1970 Black September uprising against King Hussein caused thousands of casualties and resulted in the PLO being expelled from Jordan to Lebanon. King Hussein renounced Jordan’s illegal claim to the West Bank in 1988, paving the way for the Jordan-Israel peace treaty, but also trying to withdraw Jordan from a mess of its own creation. Continuing low-level violence in Jordan is the result. Without further discussion between the Palestinians and King Abdullah II, Palestinian nationalism continues to threaten an important American ally.

A settlement based on UN Resolution 242 could include a Palestinian relationship with both Israel and Jordan that is more than autonomy and less than statehood, with economic and social integration across the Jordan River.

As an adjunct, it is useful to remember that American support for the Palestinian experiment was not full-fledged support for statehood without conditions — until the Obama administration. It was President Clinton who signed the “something less than statehood” Oslo Accords, and President George W. Bush in his 2002 Rose Garden speech on Palestinian nationalism said:

I call on the Palestinian people to elect new leaders, leaders not compromised by terror… to build a practicing democracy, based on tolerance and liberty. If the Palestinian people actively pursue these goals, America and the world will actively support their efforts.

And when the Palestinian people have new leaders, new institutions and new security arrangements with their neighbors, the United States of America will support the creation of a Palestinian state whose borders and certain aspects of its sovereignty will be provisional until resolved as part of a final settlement in the Middle East.

A Palestinian state will never be created by terror — it will be built through reform. And reform must be more than cosmetic change, or veiled attempts to preserve the status quo.

This turns full circle to President Trump’s statement on the podium with Prime Minister Netanyahu:

“The Palestinians have to get rid of some of that hate that they’re taught from a very young age. They’re taught tremendous hate. I’ve seen what they’re taught. And you can talk about flexibility there too, but it starts at a very young age and it starts in the schoolroom. And they have to acknowledge Israel — they’re going to have to do that. There’s no way a deal can be made if they’re not ready to acknowledge a very, very great and important country.”

The burden, then, is on the Arab states and the Palestinians to meet obligations dating as far back as 1948 and proceeding through 1967 and 1993. When they arrive in the 21st century, a “solution” will be found for Israel, the Palestinians, and Jordan and even, perhaps, the unhappy residents of Gaza.

But not until then.