Shifting demographics are reshaping American politics, and supporters of Israel must understand how these trends stand to reshape U.S. public opinion toward Israel. Analyzing President Obama’s re-election last November, pundits of all political stripes pointed to shifting demographics as having made the critical difference. Most frequently mentioned has been the rise of Latino voters, whose numbers at the polls (12.5 million ballots cast in 2012) nearly tripled from only two decades ago. Pundits also frequently pointed to a generation gap, whereby younger voters solidly support Democrats and older Americans vote Republican. Finally, attention is increasingly paid to dramatic changes in religious affiliation in American life, or more precisely, the growing number of Americans who lack any affiliation. According to the Pew Center, in 1972, 7 percent of Americans said they had no religious affiliation. That figure grew to 15 percent by 2007, and today stands at nearly 20 percent.

Such demographic and social trends are not only set to reshape the future of American partisan politics, they will also present substantial challenges for the longstanding, solid, bipartisan support for Israel in U.S. public opinion—a critical pillar of the U.S.-Israel relationship.

This article identifies several such trends—the partisan gap and the generational gap in support for Israel, the decline in religiosity, and the rise of Latinos—and assesses how each is affecting U.S. public opinion toward Israel. While the first three look set to chip away at support for Israel in the years to come, the growth in numbers of Latinos could work to strengthen support.

The Partisan Gap in Support for Israel

Once, an American’s party affiliation said little about his attitude toward Israel, but times have changed. In a poll conducted during Israel’s November 2012 Operation Pillar of Defense, 80 percent of Republicans voiced support for Israel, as opposed to only 51 percent of Democrats. When the sample is divided into conservatives and liberals, the difference is even sharper. Some 77 percent of conservatives supported Israel, with only 6 percent opposed. For self-identified liberals, 37 percent supported Israel and 27 percent opposed.

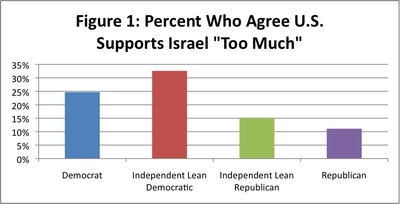

An analysis of Pew survey data reveals that those who identify with the Democratic Party were 14 percent less likely to approve of current levels of U.S. support for Israel than Republicans, and 12 percent more likely to say the U.S. supports Israel “too much.” Regardless of a respondent’s age, income, education, race, religion, and attendance at religious services (and whether controlling for these factors independently or concomitantly), this partisan gap remains unchanged.

Moreover, self-identified “independents” who lean (and thus usually vote) Democratic are even less supportive of Israel than are self-identified Democrats. Democratic-leaning independents were almost 23 percent less likely to support Israel than Republicans (and 15 percent less than the average American). As above, even when respondent age, income, education, race, and religion were taken into account, these Democratic-leaning independents were still 20 percent less likely to support Israel than Republicans (and approximately 12 percent less than the average American). Nearly identical results emerged from an analysis of those who thought the U.S. supported Israel “too much” (Figure 1).

Moreover, self-identified “independents” who lean (and thus usually vote) Democratic are even less supportive of Israel than are self-identified Democrats. Democratic-leaning independents were almost 23 percent less likely to support Israel than Republicans (and 15 percent less than the average American). As above, even when respondent age, income, education, race, and religion were taken into account, these Democratic-leaning independents were still 20 percent less likely to support Israel than Republicans (and approximately 12 percent less than the average American). Nearly identical results emerged from an analysis of those who thought the U.S. supported Israel “too much” (Figure 1).

This partisan gap in support for Israel has not escaped attention. Observers have credited a variety of theories, from growing liberal wariness toward the use of force (and connecting that to Israeli use of force) to the more fundamental trend of widening polarization in U.S. politics. Whatever the underlying cause, the basic result is clear: the partisan gap is real, and it has grown.

The Generational Gap

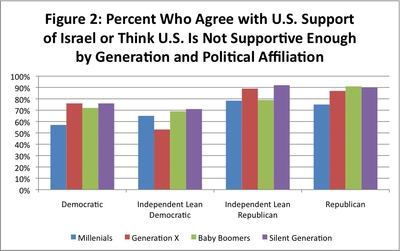

A second, highly pronounced trend is the generational gap: so-called “Millennials” (18-30 year-olds) are substantially more likely to be critical of Israel than older generations, particularly “Baby Boomers” (born 1946-1964) and the “Silent Generation” (born 1925-1945), though this is generally the case for Generation X (between the Baby Boomers and the Millenials) as well. As shown in Figure 2, this gap largely holds across political affiliation. As in the analysis of the partisanship above, controlling for a host of other factors did not change this gap at all. Republican Millennials, for example, are less supportive of Israel than Republican Baby Boomers.

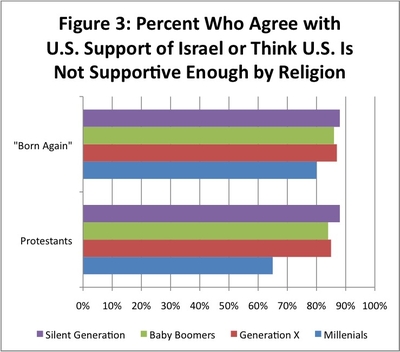

When examining religious affiliation, this generational shift is found to be particularly strong among self-identified Protestants. This said, support among self-identified “born again” Christians has been less affected (Figure 3).

When examining religious affiliation, this generational shift is found to be particularly strong among self-identified Protestants. This said, support among self-identified “born again” Christians has been less affected (Figure 3).

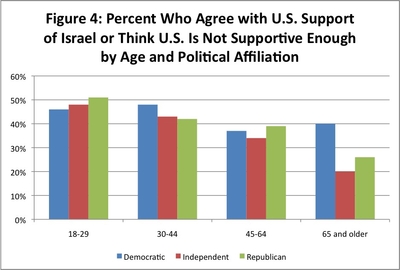

Two alternate explanations could account for the data: either a shift in public opinion is actually taking place, or younger generations are usually less supportive of Israel and become more supportive as they age. The answer emerges in comparing the findings to two joint nationwide CBS/New York Times polls from October 1977 and April 1978 (Figure 4). Interestingly, the generational gap then was the opposite of the generational gap today: retirees (65 and older) were least supportive of Israel, with 18-29 year-olds the most supportive. Again, this pattern was substantial and statistically significant regardless of other factors (i.e., race, religion, party affiliation, ideology, and education).

Two alternate explanations could account for the data: either a shift in public opinion is actually taking place, or younger generations are usually less supportive of Israel and become more supportive as they age. The answer emerges in comparing the findings to two joint nationwide CBS/New York Times polls from October 1977 and April 1978 (Figure 4). Interestingly, the generational gap then was the opposite of the generational gap today: retirees (65 and older) were least supportive of Israel, with 18-29 year-olds the most supportive. Again, this pattern was substantial and statistically significant regardless of other factors (i.e., race, religion, party affiliation, ideology, and education).

This suggests that the first explanation is correct: generations seem to develop views toward Israel that guide their opinions throughout their lifetimes. If so, the relatively less pro-Israel positions held by today’s Millennials are unlikely to fade over time, just as their elders have maintained robust support for Israel over the past 35 years.

The Decline in Religiosity

America is often thought of as a religious country, at least in comparison to a supposedly “godless” Europe. The American reality, though, is more complex. Religiosity in America is declining at a substantial rate, impacting on American public support for Israel.

White Protestants, for centuries the social and demographic backbone of America, have declined from 39 percent of the U.S. population in 2007 to 34 percent in 2012. During the same period, the percentage of so-called “Nones”—those who have no religious affiliation—rose sharply, from 15.3 percent to 19.6 percent. This category of “Nones” includes atheists and agnostics, though most are those who simply respond that they have no religious affiliation.

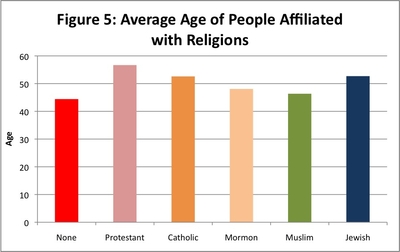

Largely, the trend is not one of individual Americans abandoning religion; rather, “generational replacement” is responsible for the change, with older, more religious Americans being replaced with younger, less affiliated individuals. Indeed, looking at data from polling respondents, “Nones” are by far the youngest of all religious groups; consequently, this trend may well accelerate in the generation to come (Figure 5).

Largely, the trend is not one of individual Americans abandoning religion; rather, “generational replacement” is responsible for the change, with older, more religious Americans being replaced with younger, less affiliated individuals. Indeed, looking at data from polling respondents, “Nones” are by far the youngest of all religious groups; consequently, this trend may well accelerate in the generation to come (Figure 5).

This stark demographic shift is a cause for concern for Israel, or at least a potential cause for change in an Israeli outreach strategy that has prioritized Evangelicals in recent decades.

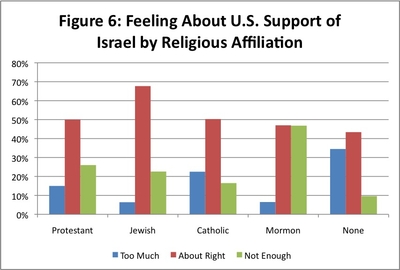

American Protestants are more likely to be pro-Israel than the average American, with “born again” Christians particularly supportive. On the other hand, in statistical analysis of the polling data (see Figure 6), compared to Protestants, “Nones” are 23 percent less likely to support Israel and 19.5 percent more likely to say the U.S. is “too supportive” of Israel. Among this group, atheists show particularly weak support (42 percent more likely respond “too supportive”), followed by agnostics (25 percent more likely), and those who identify as “nothing” (15 percent more likely).

American Protestants are more likely to be pro-Israel than the average American, with “born again” Christians particularly supportive. On the other hand, in statistical analysis of the polling data (see Figure 6), compared to Protestants, “Nones” are 23 percent less likely to support Israel and 19.5 percent more likely to say the U.S. is “too supportive” of Israel. Among this group, atheists show particularly weak support (42 percent more likely respond “too supportive”), followed by agnostics (25 percent more likely), and those who identify as “nothing” (15 percent more likely).

Demographic movement away from Protestantism and toward those with no religious affiliation could lead to a weakening of support for Israel over time. Given that “Nones” are the fastest-growing religious cohort in America, and that they account for more than a quarter of Democrats (27 percent), Israel and its supporters must learn how to engage them.

The Rise of Latinos

Of the emerging demographic trends in the United States, none has received more attention than the rise of Latinos. An estimated 52 million Latinos live in the U.S., of which, nearly half were born abroad. With an estimated 800,000 Latino children reaching voting age every year, this sector is expected to account for 40 percent of the growth in the number of eligible voters by 2030. Despite relatively low rates of voting—50 percent versus approximately 65 percent for whites or blacks—the sheer overall growth of Latinos will continue to impact greatly on U.S. elections.

At first blush, American Latinos appear almost identical to the average American in their support of Israel. Yet, Latinos are on average younger and more Democratic-leaning than the average American. In other words, given Latinos’ other demographic characteristics, one would expect them to be less supportive of Israel than average. In fact, when taking into account the three factors discussed previously, Latinos are actually 7 percent more likely to support of Israel than the average American; and the figure rises to nearly 9 percent when taking into account income, education, and church attendance.

The growing presence and electoral power of Latinos, then, is likely a positive trend for Israel, especially as they are now identifying or leaning Democratic by large margins. Consequently, this group could become a new component of the future pro-Israel coalition among the Democratic base. Many pro-Israel organizations have already begun outreach efforts for Latinos, but efforts to solidify support must be expanded as this community gets its footing and begins to take a greater interest in foreign affairs.

A Targeted Approach

Overall polling numbers on U.S. pro-Israel sentiment—with their near-record high of 63 percent support (according to Gallup)—could induce a false sense of security. Looking behind the numbers, the composite of the social and demographic trends paints a starker picture. Importantly, the three main trends working against Israel (partisan, generational, and religious) are not simply describing the same people. Each factor has an impact (~13-17 percentage points) almost entirely independent of the others. So, for example, an older (Silent Generation), Protestant Republican would most likely (79 percent) say he or she supports the U.S. stance on Israel. However, a Millennial, Democratic “None” would be unlikely (33 percent) to support the present U.S. stance on Israel.

If Israel and its supporters must take American demographics as they find them, how can these challenges be met? In particular, how can Israel and its supporters maintain grassroots support among Democrats? Part of this effort will include stepping up engagement with segments of the population that are on the rise. Continued focus on university campuses seems justified as a key tool for closing the generation gap. With Latinos, engagement efforts are well underway, especially by American Jewish organizations.

Far more challenging will be the engagement of “Nones.” The rising disaffiliation from religion may be part of a growing disaffiliation from social institutions writ large, a trend made famous by scholar Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone. “Nones,” therefore, might not only be unreachable through churches, they might be less affiliated with all manner of community groups as well. If so, pro-Israel forces must allocate more resources toward improving their understanding regarding where this cohort gets its information and, most importantly, from whom it takes its political cues. Perhaps, for instance, this sector might best be engaged by shifting part of pro-Israel groups’ efforts from mass media to niche media, reaching a smaller target audience but with more precision and effect. While outreach efforts toward Latinos seem better developed, strategies for reaching “Nones” are perhaps even more important—and more challenging.

Winning the support of liberals and “Nones” will require working with and through organizations that are ideologically inclined to the left, and indeed, many American Jews have argued that a single organization can no longer speak for all supporters of Israel. In an era of increased polarization and social fragmentation in American society, no single organization can effectively influence opinion in all segments of the American public. While this may disconcert Jewish community leaders who prize solidarity, the trend may in fact prove a blessing.

Over the course of the next several decades, American public opinion regarding Israel will likely become more divided. Israel’s policymakers should consider the strategic implications. The challenge is to maximize U.S. public support, where much can be done, and then to identify other political and geopolitical strategies to compensate for any incremental decline in public support. A targeted approach that focuses on these growing demographic segments in American society is the best path forward.

Cameron S. Brown is a Neubauer research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS). Owen Alterman is a research fellow at INSS. The authors thank Rachel Beerman and Tamar Levkovich for their research assistance. A more detailed version of this article was published in Strategic Assessment.