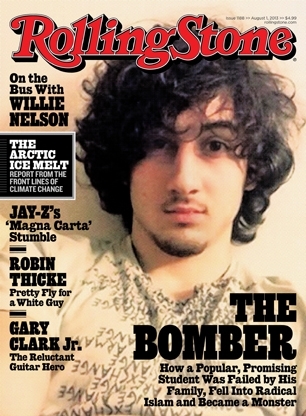

The fallout continues from the Rolling Stone‘s decision to put the accused Boston Marathon bomber, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, on the cover of the August 1st, 2013 edition. The glamour shot of the younger, 19-year-old Tsarnaev brother shows him in an Armani shirt, scruffy, unsmiling, and has drawn visual comparisons to the pictures of legendary musicians Jim Morrison of The Doors and Bob Dylan who previously graced the iconic magazine’s cover. Most news coverage focuses on the cover photo: Is this elevating Dzhokhar to rock star status? Is it too glamorous? Likewise, much of the public’s anger has been directed at the magazine’s decision seemingly to create a controversy and sell more copies at the expense of the three people killed and the 260 injured during the Boston attack.

The fallout continues from the Rolling Stone‘s decision to put the accused Boston Marathon bomber, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, on the cover of the August 1st, 2013 edition. The glamour shot of the younger, 19-year-old Tsarnaev brother shows him in an Armani shirt, scruffy, unsmiling, and has drawn visual comparisons to the pictures of legendary musicians Jim Morrison of The Doors and Bob Dylan who previously graced the iconic magazine’s cover. Most news coverage focuses on the cover photo: Is this elevating Dzhokhar to rock star status? Is it too glamorous? Likewise, much of the public’s anger has been directed at the magazine’s decision seemingly to create a controversy and sell more copies at the expense of the three people killed and the 260 injured during the Boston attack.

Is a picture really worth a thousand words? Perhaps. But the outcry over the photo misses the larger point: Today, a radical terrorist could look like our neighbor, our kids—like every day Westernized people. The Fort Hood shooter, Maj. Nidal Hasan, and the Times Square bomber, Faisal Shahzad, both looked like average Joes before becoming infamous for their actions. The uncomfortable truth is that the new face of jihad can be anyone—and that is a fresh realization for many Americans.

When America awoke on September 11, 2001, that evil had a specific look; it resembled Osama Bin Laden or Khalid Sheikh Muhammad. But looking deeper, the truth is that any Muslim who believes in Islam’s political (not merely religious) supremacy and is loyal to the more radical strains of political Islamic ideology is susceptible to radicalization, whether it is in U.S. communities, across the ocean, or on the Web. And that is where the story—not the picture—in the Rolling Stone fails. It misses an opportunity to go beyond interviews with Dzhokhar’s surprised friends and look at the root causes of Islamist radicalization.

In the more than 11,000-word article, Janet Reitman weaves a narrative that pins the blame for Dzhokhar’s actions on his mentally ill older brother and even suggests that America may have failed the two brothers. Ms. Reitman explains, “what emerges is a portrait of a boy who glided through life, showing virtually no signs of anger, let alone radical political ideology or any kind of deeply felt religious beliefs.”Demonstrating how Dzhokhar was a reflection of his Cambridge, Massachusetts surroundings, she explains:

There were many, many Jahars [Dzhokhars] in Cambridge: children of immigrants with only the haziest, if idealized, notions of their ethnic homelands. One of the most liberal and intellectually sophisticated cities in the U.S., Cambridge is also one of the most ethnically and economically diverse.

So Cambridge is as American as apple pie? A friend of Dzhokhar’s described their high school:

“But that’s the kind of high school we went to,” Jackson says. “It’s the type of thing where someone could say, ‘I converted to Islam,’ and you’re like, ‘OK, cool.'” And in fact, a number of kids they knew did convert, he adds. “It was kind of like a thing for a while.”

Another of Dzhokhar’s friends, Theo, notes that his perspective on U.S. foreign policy wasn’t all that dissimilar from a lot of other people they knew. “In terms of politics, I’d say he’s just as anti-American as the next guy in Cambridge,” says Theo.

And then there is the rampant denial in American colleges that 9/11 was an attack carried out by radical Islamist terrorists. Reitman explains:

This is not an uncommon belief. Payack, who also teaches writing at the Berklee College of Music, says that a fair amount of his students, notably those born in other countries, believe 9/11 was an “inside job.” Aaronson tells me he’s shocked by the number of kids he knows who believe the Jews were behind 9/11. “The problem with this demographic is that they do not know the basic narratives of their histories—or really any narratives,” he says. “They’re blazed on pot and searching the Internet for any ‘factoids’ that they believe fit their highly de-historicized and decontextualized ideologies.

All of this should set off alarm bells. Surely an early sign in the process of Islamic radicalization would be students born in other countries who believe that 9/11 was either an inside job or carried out by the Jews. It should raise a red flag if they are in high school—under eighteen years old—and converting to Islam because it is “a thing.” All that is missing is a radical Islamist preacher to mold those young minds, whether he preaches overseas, on the Internet, or at a local mosque. It is the role of political Islam that makes this kind of terrorism unique.

We do ourselves a disservice by failing to focus on the roots of this form of radicalization. It is at our peril that the Obama administration refuses to use the term, “violent Islamist extremism” because it ignores reality. It pushes the bounds of the English language to call the Fort Hood massacre “workplace violence” rather than a terrorist act of a violent Islamist extremist. This steady march toward political correctness creates a climate where people who may see the signs of Islamist radicalization are hesitant to say anything for fear of causing trouble or being labeled “anti-Muslim.” And as Reitman’s article unwittingly reveals, the signs were there that the Tsarnaev brothers were becoming radicalized.

The Rolling Stone picture may well have angered many for adding to the aura of “jihadi cool” but it is beside the point. The larger issue is the ideology, not the look. The editors claim in an italicized explanation in the beginning of the article that it is important to “examine the complexities of this issue and gain a more complete understanding of how a tragedy like this happens.” Unfortunately, by failing to grapple with the ideology and opting for a soft narrative of the brothers, the article falls well short of that goal.