Social Security is the single largest program of the federal government, accounting for more than 20 percent of all federal spending in 2012. Indeed, by some measures, it could be considered the largest government program in the world, providing more than $774 billion in benefits to 58 million recipients last year. It is also a program facing significant financing problems that make it unsustainable over the long term.

Last year, Social Security spent $169 billion more on benefits than it took in through taxes. In part, this was the result of the temporary reduction in payroll taxes passed in 2011, and extended for an additional year in 2012, before being allowed to expire on January 1, 2013 as part of the deal to avert the fiscal cliff. However, even though the payroll tax has returned to its full 12.4 percent rate, Social Security is projected to run a shortfall this year of $79 billion.

This does not technically constitute a deficit because Social Security also received $109 billion in interest payments on the bonds in the trust fund and $114 billion in general revenue reimbursements as compensation for the temporary payroll tax reduction passed in 2010 and renewed in 2011. However, even considering those payments, Social Security will run a cash-flow deficit by 2022.

In theory, of course, Social Security is supposed to continue paying benefits by drawing on the Social Security Trust Fund until 2033, after which the fund will be exhausted. At that point, by law, Social Security benefits will have to be cut by approximately 23 percent.

The Trustfund Is Not an Asset

However, in reality, the Social Security Trust Fund is not an asset that can be used to pay benefits. As the Clinton administration’s Fiscal Year 2000 Budget explained it:

These [Trust Fund] balances are available to finance future benefit payments and other Trust Fund expenditures—but only in a bookkeeping sense. …They do not consist of real economic assets that can be drawn down in the future to fund benefits. Instead, they are claims on the Treasury that, when redeemed, will have to be financed by raising taxes, borrowing from the public, or reducing benefits or other expenditures. The existence of large Trust Fund balances, therefore, does not, by itself, have any impact on the Government’s ability to pay benefits.

Even if Congress can find a way to redeem the bonds, the Trust Fund surplus will be completely exhausted by 2033. At that point, Social Security will have to rely solely on revenue from the payroll tax—but that revenue will not be sufficient to pay all promised benefits. Overall, Social Security faces unfunded liabilities of $23.1 trillion ($25.7 trillion if the cost of redeeming the Trust Fund is included). Clearly, Social Security is not sustainable in its current form. That means that Congress will again be forced to resort to raising taxes and/or cutting benefits in order to enable the program to stumble along.

In fact, from 1999 until March of 2011, this benefit estimate was mailed to workers annually. During the Bush administration, the Personal Benefits Statement (PEBS) contained a disclaimer that:

Your estimated benefits are based on current law. Congress has made changes to the law in the past and can do so at any time. The law governing benefit amounts may change because, by 2040, the payroll taxes collected will be enough to pay only about 74 percent of scheduled benefits.”

This warning was discontinued when the Social Security Administration stopped mailing paper copies of the benefit statement, and it is not included in the online calculator. While the SSA website includes discussions of the program’s financial problems elsewhere on the website, someone looking for what his or her benefits will be would not be told that Social Security cannot pay the listed benefit.

And, there are very few options for dealing with the problem. As former president Bill Clinton pointed out, the only ways to keep Social Security solvent are to (a) raise taxes, (b) cut benefits, or (c) get a higher rate of return through private capital investment. Or as Henry Aaron of the Brookings Institution told Congress, “Increased funding to raise pension reserves is possible only with some combination of additional tax revenues, reduced benefits, or increased investment returns from investing in higher yield assets.”

Raise Taxes?

Supporters of the current Social Security system have long advocated the first of those options, bringing in additional tax revenue, notably by removing the cap on income subject to the Social Security payroll tax. Currently, workers pay the 12.4 percent payroll tax on just the first $113,700 of annual wage income. The bipartisan Commission on Fiscal responsibility and Reform recommended that this be increased to $190,000 by 2020. The Center for American Progress would remove the cap entirely on the employer’s portion of the Social Security tax. The National Committee for Preserving Social Security and Medicare has called for removing the cap for the entire payroll tax.

Eliminating the cap would give the United States the highest marginal tax rates in the world, higher even than countries like Sweden. Studies suggest that it would cost the United States as much as $136 billion in lost economic growth over the next 10 years, and as many as 1.1 million lost jobs. And, it is important to note that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) already raised payroll taxes on families earning more than $250,000 per year by 0.9 percent.

Eliminating the cap could also lead to the perverse result of actually providing a huge increase in benefits to the wealthiest retirees. That is because the benefit formula is partially based on the level of wages taxed. We could end up sending Bill Gates or Warren Buffet Social security checks for thousands of dollars each month.

Yet even this enormous tax increase would do relatively little to increase Social Security’s long-term cash flow solvency. A 2010 CBO report found that eliminating the cap completely while also changing the benefit formula so as not to provide any additional benefits would only extend the date at which Social Security begins to run a cash-flow shortfall to approximately 2030.

Eliminating the cap would, of course, extend the exhaustion date of the Social Security Trust Fund, but as we have seen above, that merely increases intragovernmental debt without actually improving the system’s finances. If the additional revenue was used to pay for what would otherwise be deficit-financed spending, removing the cap would be indistinguishable from any other tax increase. Thus we could see a marginal improvement to the government’s overall financial picture—not Social Security’s—but at the costs associated with any other tax hike.

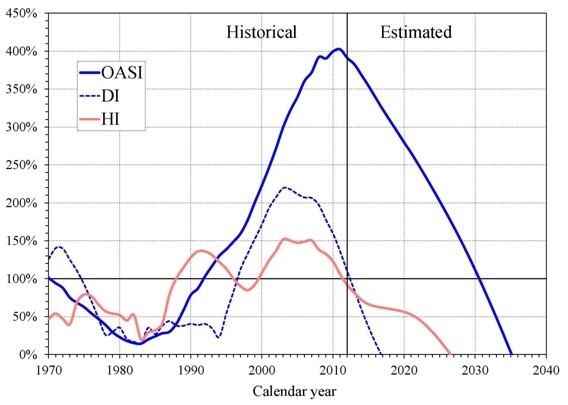

Chart: OASI, DI, and HI Trust Fund Ratios

[Asset reserves as a percentage of annual cost]

Source: Social Security Administration

OASI: Old-Age and Survivors Insurance; DI: Disability Insurance; HI: Medicare Hospital Insurance

Cut Benefits?

Cutting Social Security benefits, however, would have a positive impact on both the system’s finances and the government’s general balance sheet. Of course, there are many different ways to reduce future Social Security payments with very different impacts on recipients. The bipartisan Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, for instance, has recommended a broad array of benefit changes, including raising the retirement age to 69 by 2075, with the early retirement age rising to 64 over the same period, reforming the formula for annual cost of living adjustments (COLA’s), and trimming benefits for high-income recipients.

A better approach would be to change the formula used to calculate the accrual of benefits so that they are indexed to price inflation rather than national wage growth. Since wages tend to grow at a rate roughly one-percentage point faster than prices, such a change would hold future Social Security benefits constant in real terms, but eliminate the benefit escalation that is built into the current formula. Estimates suggest that making this change alone would result in a 35 percent reduction in Social Security’s currently scheduled level of benefits, bringing the system into balance by 2050. Variations on this approach would apply the formula change only to higher income seniors, preserving the current wage-indexed formula for low-income seniors.

Other benefit reductions that have been discussed at one time or another include: increasing the number of years included in income averaging as part of the benefit formula from 35 to 38 years, restructuring spousal benefits, and various means/asset-testing schemes. But, Social Security taxes are already so high, relative to benefits, that Social Security has quite simply become a bad deal for younger workers, providing a low, below-market rate-of-return.

Save and Invest

It makes sense, therefore, to combine any reduction in government-provided benefits with an option for younger workers to save and invest a portion of their Social Security taxes through individual accounts. A proposal by scholars from the Cato Institute that combines the wage-price indexing proposal described above with personal accounts equal to 6.2 percent of wages, was scored by actuaries with the Social Security Administration in 2005 as reducing Social Security’s unfunded liabilities by $6.3 trillion, roughly half the system’s predicted shortfall at that time. If the Cato plan had been adopted in 2005, the system would have begun running surpluses by 2046. Indeed, by the end of the 75-year actuarial window, the system would have been running surpluses in excess of $1.8 trillion. At the same time, SSA actuaries concluded that average-wage workers who were age 45 or younger could expect higher benefits under the Cato proposal than Social Security would otherwise be able to pay. While there is no more current scoring available, there is no reason to presume that savings or benefits would be substantially different today.

Personal accounts would also solve some of the other problems with the current Social Security system. Under the current system, workers have no ownership of their benefits; they are left totally dependent on the good will of 535 politicians to determine what they will receive in retirement. Moreover, benefits are not inheritable, and the program is a barrier to wealth accumulation. Finally, the current program unfairly penalizes African Americans, working women, and others. In short, it is a program crying out for reform. By giving workers ownership and control over a portion of their retirement funds, personal accounts are the only reform measure that deals with those issues.

Of course opponents of personal accounts have pointed to the recent struggles of the stock market to suggest that they are too risky to be relied on for retirement. The reality, however, is that despite recent volatility in the market, long-term investment represents a remarkably safe retirement strategy.

The failure of President Bush’s disastrous campaign for personal accounts is widely believed to have taken the idea off the table for the foreseeable future. None of the recent deficit commissions included personal accounts in their recommendations. However Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) included a proposal for personal accounts in his Roadmap for America’s Future, although this proposal did not make it into later iterations of the Ryan budget plans. This proposal would allow workers under age 55 the option of privately investing slightly more than one third of their Social Security taxes through personal retirement accounts. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that Ryan’s proposal would gradually reduce Social Security’s budget shortfall and, ultimately, restore the program to cash-flow solvency by 2083.

Several new representatives and senators elected in the 2010 and 2012 appear sympathetic to personal accounts, meaning that a combination of benefit reductions and personal accounts remains not only the best policy option for Social Security reform, but also a viable political option.

Social Security is not sustainable without reform. Simply put, it cannot pay promised future benefits with current levels of taxation. Yet, raising taxes or cutting benefits will only make a bad deal worse. At the same time, workers have no ownership of their benefits, and Social Security benefits are not inheritable. This is particularly problematic for low-wage workers and minorities. Perhaps most importantly, the current Social Security system gives workers no choice or control over their financial future.

It is long past time for Congress to act.

Michael Tanner is a senior fellow with the Cato Institute, where he directs research on a variety of issues, including healthcare, social welfare policy, and Social Security.