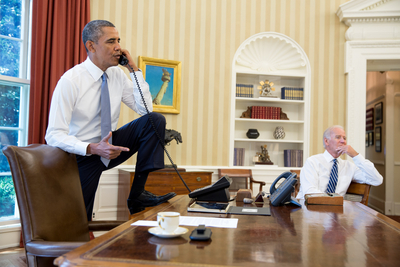

President Barack Obama talks on the phone in the Oval Office with House Speaker Boehner, Saturday, August 31, 2013. Vice President Joe Biden listens at right. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza) |

Having decided upon a military response to the latest chemical-weapons attack in Syria, President Obama should take care to calibrate the mission to suit his objective. The first question is: What would be the overall goal of a military strike? Is it to punish the regime, prevent a repeat attack, alter the balance of power in the Syrian civil war, or bring about the end of Bashar Assad’s rule as he called for two years ago? Each option necessitates a different military strategy and would shift the priority list of potential targets inside Syria.

A clear policy should guide the administration’s strategy and that, in turn, would dictate the appropriate tactics. Conversely, acting tactically rather than strategically frequently does more harm than good. According to the mission parameters delineated by the president, he now seeks congressional approval to employ an expensive and empty tactic, a gesture designed to send a message rather than alter behavior or the balance of power.

Mr. Obama’s initial public thoughts on the matter came Wednesday in a PBS interview where he suggested “limited, tailored approaches, not getting drawn into a long conflict” such as Iraq. The response would be “clear and decisive but very limited” like sending “a shot across the bow.”

In his statement delivered Saturday, Mr. Obama called the chemical weapons attack “an assault on human dignity” and rendered his decision: “I have decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets. This would not be an open-ended intervention. We would not put boots on the ground. Instead, our action would be designed to be limited in duration and scope. But I’m confident we can hold the Assad regime accountable for their use of chemical weapons, deter this kind of behavior, and degrade their capacity to carry it out.” In short, the president seeks a punitive military response designed to punish the Syrian regime and hopefully make Assad think twice before using chemical weapons again.

There are some possible benefits to pursuing the punishment option. It includes the political goals of holding the Syrian regime responsible for chemical-weapons use, bolstering deterrence against its further use, and encouraging a break within the regime itself. It may even recover some of Washington’s deterrence credibility among friends and foes that have seen White House red lines repeatedly crossed with no consequences imposed.

However, the risk is that doing something too limited and symbolic will embolden the regime and its allies instead. Engaging in this form of slap on the wrist might merely define for Mr. Assad what the acceptable parameters are for killing his people. It also could invite future challenges if the top echelons of the regime remain unaffected by the very design of the punishment.

Short of working to bring about the end of the regime, if the Obama administration aims to prevent the further use of chemical weapons and alter Mr. Assad’s behavior, something more meaningful is required beyond launching a few dozen cruise missiles. Crafting a strategy to achieve those limited objectives requires degrading the regime’s military capabilities and altering its risk calculus. Such strikes should inflict serious damage on the targets and be conducted in a manner that is seen, heard and felt by both the regime and the opposition. Targets should include military, intelligence and operational headquarters along with command-and-control facilities, barracks and facilities associated with the 4th Division and Republican Guard Armored Divisions, and any units that participated in the chemical-weapons attack.

Most importantly, in order to change Mr. Assad’s behavior, he, his family and regime leaders should be targeted. Instead of limiting the mission’s scope, Mr. Obama should make public that the United States stands ready to conduct future, asymmetrical strikes. It is the only way Mr. Assad’s risk calculus might change and it could hasten the end of the conflict. It also would reinforce the notion that there are levels of barbarity unacceptable to the international community and demonstrate that American red lines are meaningful. That message would be punishing, and it would resonate. It would boom louder than a shot across the bow.

Here, a mix of old adages rings true: If you can’t do something right, then don’t do it at all. The phrase, “a shot across the bow,” comes from the naval practice of firing a cannon shot across the front of an opponent’s ship. It is designed to stop the opponent and demonstrate one’s preparedness to do battle. Actions speak louder than words. While it is commendable that the Obama administration may finally be willing to act, the limited shot across Syria’s bow that he envisions will likely achieve none of his stated objectives and may end up damaging the American ship of state as well.