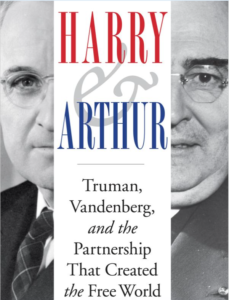

If you think World War II ended in 1945, Harry & Arthur: Truman, Vandenberg and the Partnership that Created the Free World is a book for you.

Taking readers through the politically, economically, socially, and militarily difficult wars that continued after VE Day, Harry & Arthur is also a well-crafted, sympathetic look at a time when ideas mattered more than politics. Mostly.

The post-war wreckage of Europe was exacerbated by two unusually cold winters – people starved to death in 1947. Not only were crops destroyed, but the trade and banking systems that allowed countries to finance sales and purchases were gone as well. Stalin moved quickly from wartime ally to opportunist who saw in the possibility of extending Russia’s borders beyond the quick political annexation to Central and Eastern Europe well into Western Europe – Greece and Italy as well as Eurasian Turkey being immediate targets. It is easy to forget now how close Italy and Greece came to communist takeover.

The United States, living, breathing and prosperous – but war weary in the most literal sense, and traditionally isolationist – had to decide how involved it wanted to be in the post-war reordering of economics and politics. It turned out that for two crucial players – Democratic President-mostly-by-accident Harry Truman and Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg – the answer was “very.”

Lawrence J. Haas of the American Foreign Policy Council covers their cooperation on the (often overlooked) Rio Pact that set parameters for American participation in the United Nations; the Truman Doctrine pledging American defense against Communism virtually around the globe; the reconstruction of European economic institutions through the Marshall Plan; and the establishment of NATO.

All were accomplished through what seems at first to be an odd partnership. Truman was, by nature, an internationalist. Vandenberg moved in that direction slowly until 1941:. “My convictions regarding international cooperation and collective security for peace took firm form on the afternoon of the Pearl Harbor attack. That day ended isolationism for any realist.”

As the story progresses, the partnership appears less odd. There was fundamental agreement on the movement of Russian dictator Josef Stalin away from wartime collaboration with the West to the belief that Russia could capitalize on European weakness and American distance from the problem after 1945. According to Haas:

They shared a guiding vision for what the United States must do on the world stage at a perilous time. They recognized that America must shed its isolationist tendencies, assume global leadership, help rebuild Europe’s economy and lead the fight against aggressive Soviet expansionism.

And so, beginning with the negotiations over the establishment of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945, they worked to make it happen.

Greatly influenced by Wilson’s failure to have the U.S. participate in the League of Nations, Truman, ever an honest man, acknowledged that Wilson’s dismissal of Senate Republicans – the majority – was a mistake, and possibly the undoing of the whole mission: “It was my opinion that if President Wilson had had the leaders of the Congress in his confidence all the time and had trusted them, he would not have been defeated on the League of Nations.”

Truman sent the Republican Vandenberg to the preliminary meetings of the UN in San Francisco. It was there that Vandenberg saw first-hand the possibility of Russian obstructionism. Without instant communications, or even reliable telephones, Truman was trusting Vandenberg to work with Cabinet members and foreign dignitaries a long way from home.

1946 was a crucial year. From George Kennan’s “Long Telegram” to Vandenberg’s “What is Russia up to now?” speech in late February, the anti-communist stage was being set. Vandenberg asked on the Senate floor:

We ask it in Manchuria. We ask it in Eastern Europe and the Dardanelles. We ask it in Italy where Russia, speaking for Yugoslavia, has already initiated attention to the Polish Legions. We ask it in Iran. We ask it in Tripolitania. We ask it in the Baltic and the Balkans. We ask it in Poland. We ask it in the capital of Canada. We ask it in Japan. We ask it sometimes even in connection with events in our own United States. What is Russia up to now?”

Truman’s answer was, “Nothing good.”

The 1946 election – which Truman was expected to lose – complicated their relationship, but Vandenberg proved entirely committed to the association, going so far as to eschew national campaigning. They were rewarded in November with Vandenberg taking 67% of the Michigan vote for reelection and Truman slipping back into office.

The next collaboration was for the often-misunderstood Marshall Plan. Contrary to popular opinion (most recently by international do-gooder Bono) the Marshall Plan was not about money. By 1947, the U.S. had already been giving enormous sums of money (and food aid) to Western European countries, but it was short-term relief, “like skippers on a leaky boat, plugging holes to ensure that it didn’t sink, but leaving it ill-equipped to make its way to shore through increasingly turbulent waters.” A comprehensive strategy was needed and Marshall provided the crucial intellectual point:

There must be some agreement among the countries of Europe as to the requirements of the situation and the part those countries themselves will take in order to give proper effect to whatever action might be undertaken by this government. It would be neither fitting nor efficacious for this government to undertake to draw up unilaterally a program designed to place Europe on its feet economically. This is the business of the Europeans. This initiative, I think, must come from Europe. The role of this country should consist of friendly aid in the drafting of a European program and of later support of such as program so far as it may be practical for us to do so.

“With isolationist sentiment running high in the isolationist Midwest, Vandenberg received lots of mail from unhappy constituents,” Haas noted.

Haas puts useful and interesting emphasis on Vandenberg, the lesser known of the principals, who emerges as something of a hero, habitually using questions in the Senate to evoke answers from Administration officials that would respond to Republican concerns and make the points Republicans were most interested in hearing. He fed the press and took to the Senate floor to expound upon the virtues of various Truman-instigated, and very expensive, plans.

At the same time, it should be said that he was considered pompous and touchy about his privileges. But he periodically swallowed his pride and overlooked slights – intentional and not – from the administration. There were exceptions, and the announcement of the Marshall Plan by Secretary of State Dean Acheson in a speech at Delta State Teacher’s College in rural Mississippi, complete with the understanding that it would be expensive, infuriated Vandenberg, who was having trouble with isolationist and budget-cutting Republicans on the Hill. He demanded a meeting with Truman and – with Marshall and Acheson in the room – Vandenberg unloaded. “I want you to understand from now on, that I’m not going to help you with crash landings unless I’m in on the takeoff.”

But committed to the security of Europe, he shepherded the Marshall Plan though an unhappy Senate.

Acheson may have provided the highest political compliment in history when he described Vandenberg as, “born to lead a reluctant opposition into support of governmental proposals that he came to believe were in the national interest.” But he also teasingly referred to an incident with Vandenberg as, “Without warning a hurricane struck. Its center was filled with a large mass of cumulonimbus cloud, often called Arthur Vandenberg, producing heavy word fall, “before adding, “I have come to have great respect and considerable admiration” for the Republican Senator.

Harry & Arthur is an important, well-written, well-researched, authoritative, and fascinating look at a crucial four years in American and world history. It is a snapshot taken with a Kodak Brownie camera, a perfect capture of its time and place.

Unfortunately, after 273 well-disciplined pages, Haas goes for a national security selfie, giving in to the impulse to look at us now. He compares that time with this; that crisis with this; that enemy with this. He makes no direct comparison of that President with this, but does quote President Obama on his view of current threats. In Chapter 23, he tries to bring NATO up to date, walking it through the collapse of the Soviet Union and wondering, “Whether in 2015 and beyond, NATO would muster the military forces and political will to stop Putin was open to question.” The Epilogue is the world in 2015 as Haas sees it – a personal rumination, diverging from what had up to that point been an illuminating dip into our country’s recent past.

He should have left it as a Kodak moment.