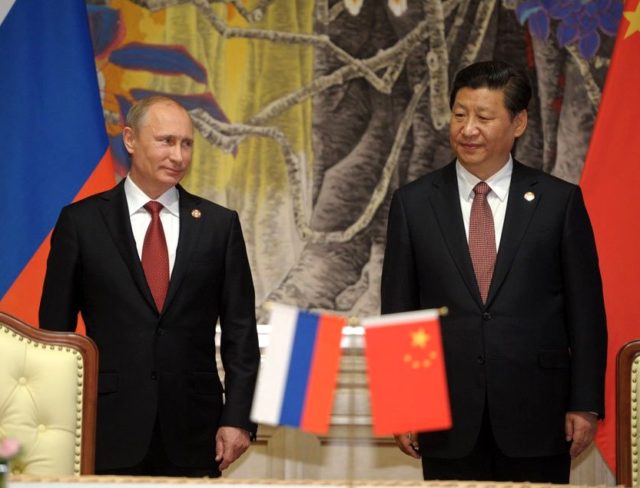

Western observers inexplicably dismiss all signs of a Russo-Chinese alliance with the argument that underlying incompatibilities between Russia and China will prevent any real cooperation. Yet while disappointments and tensions exist between them, all the evidence points to the formation of an alliance, or what the Russian analyst Alexander Gabuev calls “an asymmetric interdependence,” where Moscow depends more on Beijing than vice versa. Indeed, Russian officials have, since 2014, spoken openly in terms of an alliance and used that word.

Russian President Vladimir Putin most recently stated that:

As we had never reached this level of relations before, our experts have had trouble defining today’s general state of our common affairs. It turns out that to say we have strategic cooperation is not enough anymore. This is why we have started talking about a comprehensive partnership and strategic collaboration. “Comprehensive” means that we work virtually on all major avenues; “strategic” means that we attach enormous inter-governmental importance to this work.

This is too close to advocacy of an alliance to be coincidental. Putin has also spoken of Russia catching the wind of China’s growth in its sails and derided the China threat theory. He also indicated that Russia and China would begin discussing a vast “Eurasia project,” presumably comprising both China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). Presumably these talks are based upon China’s earlier assent to the idea of linking Russia’s plans for integrating Eurasia through the EEU to the OBOR project.

China’s Victory over Russia

This sequence actually displays China’s victory over Russia and Russia’s inability to compete with China. Russia now is merely a “junior brother” in such endeavors. Typically, China graciously but decisively punctured Russia’s grandiloquent Eurasian and great power pretensions. And Russia’s recklessness and failure to reform greatly assisted in the process. Given the expansive geostrategic benefits that China will obtain while realizing its OBOR vision, the evolving bilateral relationship on this issue portends a massive and decisive Russian strategic defeat in Eurasia rendering it here, as in energy, China’s raw materials appendage. Furthermore because the EEU’s original vision included restricting Chinese trade in Central Asia, China’s integration of Russia’s project to its own subordinates Russia’s program to China’s vision.

Second, China has not invested in Russia to the degree that Russians had expected or hoped for, because of the Chinese economic downturn and because Chinese investment agencies will not provoke U.S. banking sanctions and are quite disenchanted with Russia’s failure to fulfill the terms of previous economic agreements such as those from 2009. Consequently many Russian analysts have admitted that the so-called pivot to Asia is more talk than action and this pivot actually is a rather ungratifying pivot only to China. Moscow depends more on Beijing than is good for it. Although some analysts still extol China’s willingness to participate with Russia in this vast yet unfocused plan for a Eurasian bloc, nobody can overcome the fact that Eurasian countries’ trade with Russia, including China’s, has steadily fallen along with Russian investment. Similarly there are those analysts who, following Putin, proclaimed the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) a paradigm of successful cooperation when it has still done nothing visible or tangible to promote regional security and its achievements (whatever they may be) remain obscure.

Consolidating Former Soviet Republics

Importantly, if Russia cannot compete practically with China in organizing a genuine Eurasian economic community, Russia cannot compete as a truly independent and great Asian power. For a precondition of achieving that latter goal is consolidating a continental bloc of former Soviet republics around Russia. Since China, but not Russia is doing this, the chances for any success in Russia’s “grand strategy” regarding Asia diminish commensurately. Yet Russian policymakers still openly advocate alliance with China. In 2014 Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said:

I can’t fail to mention Russia’s comprehensive partnership with China. Important bilateral decisions have been taken, paving the way to an energy alliance between Russia and China. But there’s more to it. We can now even talk about the emerging technology alliance between the two countries.

Lavrov immediately followed by observing, “Russia’s tandem with Beijing is a crucial factor for ensuring international stability and at least some balance in international affairs.” Simultaneously, Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu and his deputy, Anatoly Antonov, speaking in Beijing, openly advocated a military alliance with China. Shoigu argued that Russia and China confront not only U.S. threats in the Asia-Pacific but also U.S.-orchestrated “color revolutions” [Ed. Political movements that emerged in several former Soviet Republics and formerly Russian-dominated societies.] and Islamic terrorism. Therefore, “The issue of stepping up this cooperation [between Russia and China] has never been as relevant as it is today.”

Specifically, Shoigu advocated enhanced but unspecified bilateral Sino-Russian security cooperation and within the SCO. Shoigu and Antonov included Central and East Asia. Both men decried U.S. policies that allegedly fomented “color revolutions” and support for Islamic terrorism in Southeast and Central Asia. Shoigu further stated that, “In the context of an unstable international situation, the strengthening of good-neighborly relations between our countries acquires particular significance. This is not only a significant factor in the states’ security but also a contribution to ensuring peace throughout the Eurasian continent and beyond.”

Security Cooperation?

This overture fundamentally reversed past Russian policy to exclude China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) from Central Asia and retain the option of military intervention there solely for itself. This gambit signifies Russia’s growing dependence on China under mounting Western political and economic pressure. Such an alliance would also reverse Chinese policy that has heretofore shunned military involvement in Central Asia and characteristically sought to foist those responsibilities onto Russia.

This alliance would mark a revision of past Chinese policies and presage movement toward a genuine Sino-Russian military-political alliance in Central Asia against terrorism and Islamism in all its forms. Chinese President Xi Jinping, for his part, clearly seeks Russian support for Chinese policy in East Asia, and Russia now supports solving the South China Sea issue without U.S. participation and has an identity of views with China regarding Korea. So here China is gaining on Russia.

Moreover, Russia’s new defense doctrine proposes to “coordinate efforts to deal with military risks” in the SCO’s common space and provides for the creation of joint missile defense systems. While Moscow has previously pursued this with the West, this could also be a warning or offer to go with China in the creation of such systems. Thus Shoigu stated that, “During talks with Comrade Chang Wanquan, we discussed the state and prospects of Russian-Chinese relations in the military field, exchanged opinions on the military-political situation in general and the APR [Asia-Pacific Region] in particular…We also expressed concern over U.S. attempts to strengthen its military and political clout in the APR.” He added, “We believe that the main goal of pooling our effort is to shape a collective regional security system.”

If this is not an offer for an alliance then we need to redefine the term.

Russia as the Junior Partner

Even though Putin, in 2014, reiterated that joining an alliance subordinates Russia to the other parties and undermines its sovereignty, Russia clearly called for a more formalized alliance. China sidestepped the issue but is clearly prepared to upgrade cooperation with Russia, especially since Moscow’s rising dependence upon its largesse and support can be turned to China’s account. Indeed, in their book about the Russian Far East, Artem Lukin and Renssalear Lee explicitly say that Putin has offered China an alliance. If this accurately states the situation, then even analysts who write about Russian foreign relations generally – and not just experts on China – understand that this means Russia is becoming not just a junior partner to China but also losing a place of primacy on the overall international agenda given the dynamism of Asia’s economies and the many arenas of geopolitical strife there.

Nevertheless, and despite this risk, there clearly are Russian champions of closer ties to China if not an alliance. Apparently the military and the Ministry of Defense are among them even though these particular elites fully understand that China, by virtue of its rising power and capability, as well as the increasing reach of its capabilities and interests, e.g. in the Arctic, could constitute a military threat to Russia.

Military Sales and Cooperation

By 2014 Shoigu and Antonov were advocating an alliance, Moscow was selling China the crown jewels of Russian defense production such as the S-400 air defense system, and SU-35 fighter plane, and the Amur-class submarine. Moreover, regular joint naval exercises have taken place, not only in the Far East but also in the Mediterranean, signifying Russian acceptance of China’s interests there and desire to lean on Chinese power in the Levant. Indeed, as a result of these exercises, including the most recent ones, “Aerospace Security-2016,” Russia may now sell China the nuclear-capable Kalibr’ cruise missile to be installed for use on Russian-made Kilo class diesel-electric submarines, even as Russia, for its own purposes, continues the ongoing combined arms build up of its Far Eastern Military District (FEMD) and overall military expansion.

The Russian Pacific Fleet also joined with China’s Navy recently to sail into the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands provoking a significant Japanese response, an action that appears senseless unless the military and the government are trying to intimidate Japan into an agreement with Russia. Although Russia backed out of selling highly capable rocket engines to China, something that had hitherto not been the case, a recent Russo-Chinese aerospace simulation of a joint response to a ballistic missile attack drill, clearly intended against the U.S., indicated “a new level of trust” between these governments. Sharing such highly sensitive information as missile launch warning systems and ballistic missile defense that “indicates something beyond simple cooperation,” according to Vasily Kashin.

Consequently Moscow’s pivot to Asia has essentially been a pivot to China, leading to a loss of maneuverability and freedom of movement in Asia and weakening the bilateral relationship, a declining reputation among erstwhile friends, and growing subordination to Chinese designs in Central, South, Southeast, or Northeast Asia.

The partnership will continue as long as a shared anti-American ideological-political discourse dominates strategic thinking. But Russia will not benefit very much and China may chafe at being attached to a reckless, declining power. Russia may not relish being subordinated to China and thereby be unable to be an Asian power any time soon. Indeed, subordination to a Chinese ally represents the ultimate irony if not crowning indignity since the entire purpose of Russian foreign policy is to assert and gain acknowledgement for Russia’s sovereign independence and greatness as a foreign policy actor across Eurasia, and the tie to China’s original purposes was to achieve those goals by relying on China.

Therefore, we should look beyond the professions of amity to realize that alliance, Putin’s apparent current default option, possesses an inherently explosive quality, not least for Russia.

Stephen Blank, Ph.D. is a Senior Fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.