“Never Again” is a pledge of Jewish defiance; Israel is the embodiment. If one is an optimist, “Never Again” is a way for the European community to verbalize that it understood the magnitude of its crimes.

But Rwanda is proof – if proof is needed – that the world still contains a lethal mix of condescension, racism, apathy, self-righteousness, and carelessness. It is also proof that the United Nations, far from preventing a holocaust (appropriately used here) simply allowed individual countries to hide behind the edifice and worse, hide their real agendas behind an impersonal bureaucracy in a First World country.

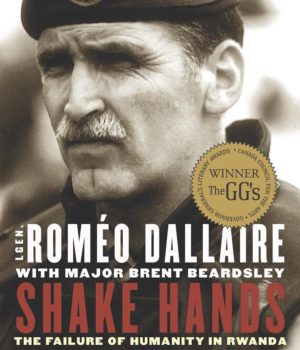

Shake Hands with the Devil is the 2003 memoir of retired Canadian LTG Romeo Dallaire, Commander of the UN peacekeeping force in Rwanda (UNAMIR). It was written years after the fact because it took that long for him to commit some of the most terrible parts to paper. Ugly as the descriptions are, one suspects there is worse still in his head. He attempted suicide four times after his return to Canada.

Dallaire was witness to the devolution of Rwanda from a tense country whose major warring factions had, in fact, signed a peace agreement, into the depths of genocide. In the early months of his deployment, Dallaire sent detailed papers to the UN about how the ceasefire was unraveling and how he thought the UN could strengthen the peacekeeping force to round up weapons and protect the population from both factions. But the UN was less than interested.

After a coup in Burundi heightened tensions in Rwanda, Dallaire asked the UN for more logistical support to keep the new violence from spreading across the border. He was denied because he hadn’t requested the support earlier – that is to say, before the coup! He was denied more men, more vehicles, more radios and even more food. His request that an informant who gave UNAMIR good information about the plans of the Rwandan government for violence against the Tutsi minority be evacuated for his safety was also denied. But it was not ignored. UN Secretary General Kofi Annan demanded that the informant’s information be given to the Rwandan government!

As the killing escalated, the UN prepared to reduce UNAMIR. The U.S. proposal was that the “Security Council should adopt a resolution providing for the ‘orderly evacuation’ of UNAMIR, since it is unlikely that a cease fire would be established in the near future.” (The U.S. later agreed to send vehicles to Rwanda, but demanded payment in advance. Needless to say, the vehicles didn’t ship.) Only New Zealand suggested that UNAMIR be expanded and have its mission changed to help protect civilians. New Zealand lost. At the end of one UN session, with thousands of Rwandans dying daily, the Security Council – seeing as it was Friday – decided further discussion could wait until after the weekend.

The UN and the West were, in fact, cavalier with the fate of a small African people, but at heart, the story of Rwanda is the story of what Rwandans did. The genocide was concocted there and executed there by Rwandans. Dallaire’s determination to mitigate the disaster is commendable – although his forays into diplomacy were sometimes clearly beyond the scope of his military training – but in the end, those who controlled the weapons and the narrative controlled the genocide.

He catalogues meeting after meeting with representatives of the Rwandan government (RGF) and the rebels (Paul Kagame’s RPF, the ultimate victor and today President of Rwanda) and even meetings with the murderous Interehamwe. The various groups working under and alongside the two main factions are hard to keep separated, but suffice it to say that among them were a few good people, a great many bad people, some very bad people and depraved people. There were, actually, a few moderates in a government full of radical “genocidaires.” Mostly they died.

The Rwandan government, through its alliance with Interehamwe, ignited the genocide. But Kagame, as leader of the rebels, took an odd path to ending the war – he deliberately moved his forces slowly and kept them away from the capital, Kigali, leaving more time for the RGF to massacre people as it lost territory. Even when the killing petered out, Kagame delayed allowing people to move to find shelter and humanitarian aid.

Dallaire’s world in Rwanda was divided into three groups: the UN bureaucracy in New York, which he considered as nothing more than an impediment; the Rwandan factions themselves; and the international troops he commanded. The third is where his heart is. A military man by profession, Dallaire connected best with other military officers regardless of their origin. Troops from Senegal, Ghana, Uruguay, Tunisia, and Bangladesh were extraordinarily dedicated to the under-staffed, under-armed, and under-funded mission, and Dallaire gives them their due.

He worked with Belgian soldiers, but the government of Belgium, the former colonial power in Rwanda, proved itself racist by government decree:

[The Belgian commander] informed me that … Belgian soldiers would only be accommodated in hard buildings as per national policy… (They showed me) a national Belgian army policy directive that stated that in Africa, Belgian soldiers would never live under canvas but only in buildings… because it was imperative that they maintain a correct presence in front of the Africans.

Belgian soldiers called Rwandans a name that cannot be said in the U.S. and Rwandans, not unsurprisingly, despised the Belgians. Ten Belgian soldiers were massacred at the airport and Dallaire had trouble even having the bodies returned. Belgium removed its troops just as the genocide began.

The U.S. gets mixed reviews. In a good moment, after the U.S. had authorized the “loan” of six (yes 6) “stripped down (no guns, no radios and no tools) early Cold War era APCs,” one of his aides took a call from an NCO at the Pentagon:

[He] asked why we needed the APCs… Brent described our substantially reduced force structure, our desperate logistics state and our precarious situation on the ground, ending his explanation with: “It gives a whole new meaning to the word ‘light forces,’ doesn’t it?” The good old boy in Washington responded, “Buddy, you’ll get your APCs, good luck to you and God bless.” We got more and faster support from that one sergeant than from the rest of the United States government and armed forces combined.

So he was amazed when the Clinton administration put out a press statement after most of the killing was done, saying, “The U.S. has taken a leading role in efforts to protect the Rwandan people and ensure humanitarian assistance…provided $9 million in relief, flown about 100 Defense Department missions…strongly supported an expanded UNAMIR, airlifting 50 armoured personnel carriers to Kampala…(and is) equipping the UN’s Ghanaian peacekeeping battalion.”

“Clinton’s fibbing dumbfounded me,” Dallaire wrote. “The DPKO [Department for Peacekeeping Operations] was still fighting with the Pentagon for military cargo planes to move materiel. The Pentagon had actually refused to equip the Ghanaians as they felt the bill was too high and that Ghana was trying to gouge them.”

The most monstrous killing lasted three months, and Dallaire remained in Rwanda for a few more – in the latter chapters he becomes less patient, less tolerant, more aggressive and, frankly, less moored to reality. He sees it coming. “I was often repeating myself and becoming unrealistically demanding. I was also continuing to lose my temper.” “I realized that my manners and my sense of humor, two essentials of leadership, were fading fast.” “My dreams at night became my reality of the day and increasingly I could not distinguish between the two.” In August 1994, LTG Dallaire was reassigned.

Looking back from here and now, Dallaire’s book provides lessons for today:

- People can commit murder in horrific ways, but mass murder on the scale of Rwanda or Syria requires leadership on the inside and apathy on the outside.

- Media – radio in particular – is helpful in inciting violence.

- Moderates die first because they are dangerous.

- The UN is a perfect construct behind which to hide if you really don’t want to be involved.

- Europeans remain post-colonial with all that implies.

- PTSD is an insidious battle wound. More than 20 years after his departure from Rwanda, LTG Dallaire still takes medication and has had more than 13 years of therapy. He is a hero in Canada for his service in uniform and his post-uniformed service to struggling soldiers.

- Life continues.

A small vignette from Yosef Abramowitz, CEO of Energiya Global Capital, published in inFOCUS Magazine in 2016:

An hour outside of Kigali, Rwanda, 28,360 blue solar panels blanket a hill overlooking the Agahozo Shalom Youth Village, the home of 500 orphans from the Rwandan genocide. The field, in the shape of the African continent, not only supplies 6% of the country’s electrical generation capacity, it also is a tangible manifestation of Israeli solar know-how, Jewish ideals, and international finance.

Shoshana Bryen is Senior Director of The Jewish Policy Center and Editor of inFOCUS Quarterly.