Egypt is now facing a complex asymmetrical war on various fronts. On November 10, 2014, the Sinai-based al-Qaeda-affiliated Ansar Beit al-Maqdis (ABM), the country’s most active jihadist group, formally declared its allegiance to the Islamic State (IS). Simultaneously, on Egypt’s western flank, Libyan fighters in the city of Derna also pledged their allegiance to the Islamic State. IS has since claimed responsibility for attacks in Cairo, and may have loyal factions in the nearby Gaza Strip.

These developments are not entirely unexpected. For the Islamic State, operating in the Arab world’s most populous nation provides both credibility and legitimacy. But IS’s intrusion has been facilitated by two trends. First, Egypt has consistently neglected its periphery. The North Sinai, for example, had slipped from the control of the central government long before the rise of IS in the country. Second, while the fascination of rejectionist radicals with the concept of a medieval-style Islamic State is not new, Egypt’s combination of vulnerable land and radical sympathies makes it a particularly enticing destination.

A Lawless Region

The Sinai has long served as a hotspot for Islamic militancy. The return of the peninsula to Egyptian sovereignty as a result of the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty, and the neglect of the area by successive Egyptian governments thereafter, made it a permissive venue for radical groups in which to organize and operate. This, coupled with its proximity to the territory of the “Zionist enemy,” made the Sinai an ideal location for jihadists.

The first jihadist group to exploit the peninsula was Tawhid wal-Jihad. Founded in 1997 by two friends from the Sinai city of Arish, Khaled Mosaad and Nasseer Khamis El-Malakhi, the group focused on attacking posh southern tourist resorts in Sinai. It is believed to be behind the 2004 attack in Taba and Nuweiba, the attack in Sharm al-Sheikh the following year, and subsequently the 2006 attack in Dahab. The group’s reign of terror was short-lived, however; Khaled Mosaad was killed by Egyptian security forces in 2005, his comrade-in-arms Nasseer Khamis El-Malakhi in 2006.

Relative calm was restored in the Sinai thereafter, but radical militancy did not vanish. On the other side of the border, in Gaza, a group called Jund Ansar Allah emerged in November 2008 and briefly proclaimed “the birth of an Islamic emirate.” The Palestinian Hamas Islamic Resistance movement, which serves as the ruler of Gaza, killed Jund’s leader, Sheikh Abdel-Latif Moussa, during fighting in the city of Rafah on the border with Egypt the following August. The incident raised the alarm about Gaza-Egypt border tunnels and the potential links between Gaza radicals and Sinai-based ones, especially after 2010’s rocket attacks fired from Egypt’s Sinai on Israel’s port of Eilat and Jordan’s adjacent Aqaba.

The year 2011 was a crucial one in the jihadi evolution of the Sinai. The anti-Mubarak uprisings that spring were followed by an almost complete collapse of security in the peninsula. In that vacuum, a new, more ruthless group called Ansar Beit al-Maqdis (ABM) was formed, and soon became the most prominent Sinai-based radical faction. ABM employed al-Qaeda’s tactics, and routinely referred to and praised its leaders in its statements.

The linkages ran deeper, too. For example, Egyptian officials have alleged that a long-time Egyptian Islamic Jihad leader named Ahmed Salama Mabrouk, a subordinate of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, has played a leading role in ABM. As well, one of its main founders, Tawfiq Mohammed Freij, a veteran of Tawhid wal-Jihad and a close companion of both Khaled Mosaad and Nasseer Khamis El-Malakhi, was later described by the group itself as “one of the unique fingerprints in the history of the jihadi work in Sinai.” It was Freij who introduced the idea of attacking pipelines that supplied gas to Israel. The first of the resulting attacks was launched in February 2011, and grew to become a major tactic utilized by ABM.

Morsi’s Rule and Beyond

During the tenure of Mohamed Morsi as Egypt’s president (July 2012 to July 2013), the security situation in the Sinai did not improve. In August 2012, gunmen there killed 15 Egyptian border guards and hijacked armored vehicles to launch an attack across the Israeli border. Egypt blamed the attack on militants from Gaza, who allegedly entered Egypt through tunnels beneath the border. Subsequently, in September 2012, ABM claimed responsibility for a cross-border attack in which an Israeli soldier was killed. The same month, the multi-national peacekeeping headquarters in Sinai was also attacked.

After President Morsi’s ouster, Ansar Beit al-Maqdis intensified its attacks on the Egyptian state in a carefully crafted move to exploit the turbulent Egyptian political scene and to boost popularity among the country’s Islamist youth. In August 2013, a rocket-propelled grenade killed 25 Egyptian soldiers near Rafah, and the following month, six soldiers were killed in a double suicide bomb attack in Rafah. The same month, Egypt’s Interior Minister, Mohammed Ibrahim, survived an assassination attempt. A month later, Ansar Beit al-Maqdis released a video documenting the assassination attempt. The group was also allegedly behind the attack on security headquarters in the Sinai town of Al-Tor in October 2013, and a car bomb explosion near an Egyptian military intelligence compound in the Suez Canal city of Ismailia the same month. Later, in November, a suicide bomber rammed his explosive-laden car into a convoy of buses carrying off-duty soldiers between Rafah and Arish. In 2014, the group took a step further and shot down an Egyptian military helicopter with a surface-to-air missile, killing five soldiers.

Over the intervening years, Egyptian authorities have attempted to crack down on Ansar Beit al-Maqdis—with at least some success. In March 2014, the group announced the death of its founder, Tawfiq Mohammed Freij, and another member, Mohamed al-Sayed Mansour al-Toukhi. In April 2014, an Egyptian court formally designated Ansar Beit al-Maqdis as a terrorist group. Later, in October, the Egyptian army announced the death of another senior ABM operative, Shehata Farahan, during a raid in Rafah.

The Islamic State’s Intrusion

Following its pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State in November 2014, Ansar Beit al-Maqdis renamed itself Wilayat Sinai, or the Islamic State’s province of Sinai, to fit in with its new affiliation. Egyptian and Israeli intelligence are still in the dark about the identities of the people running Wilayat Sinai. Israel’s military admits that it doesn’t know who the military commander of the group is, and there are no indications that Egypt has better information.

The motive behind the group’s shift in loyalty was unclear. One possible cause was mobility. Prior to the announcement, ABM had been keen to prove that the killing of its senior operatives did not hamper its activities. Two weeks after Shehata Farahan was killed, the group conducted one of its deadliest attacks in North Sinai, killing at least 31 soldiers and forcing Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to declare a state of emergency in the North Sinai governorate. The edict was bad news for ABM, as it involved a curfew in North Sinai, the heavy presence of Egyptian army units, and a government decision to create a buffer zone along the Gaza border, during which it demolished thousands of homes along the border. All of these factors restricted the group’s freedom of action—and might have helped it to decide to seek more strategically advantageous support from the better funded, equipped, and increasingly popular Islamic State.

What is clear, however, is that ABM’s pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State, as Mokhtar Awad and Samuel Tadros have written, has created the specter of competition with al-Qaeda. This is because part of the organization remained loyal to al-Qaeda, and the shift to identification with IS alienated a significant number of jihadis on the Egyptian mainland. The most significant defection from the group was the loss of ex-special forces officer Hisham Ashmawy, who later formed a new group loyal to al-Qaeda called al-Mourabitoun.

This, however, did not diminish the new Wilayat Sinai’s lethality. On January 28, 2015, the group launched multiple simultaneous attacks involving car bombs and mortar rounds against several army and police positions, killing at least 26 people and causing Egyptian authorities to extend the curfew in North Sinai. The attacks did not stop, however. In March, a suicide bomber killed a civilian and wounded 30 policemen. In April, at least 14 people, mostly Egyptian policemen, were killed in separate operations when militants attacked a police station.

According to scholar Hassan Hassan, the Islamic State’s franchise in Sinai has benefited significantly from the resources and expertise of jihadists fighting in Syria and Libya. Jihadist returnees injected new life into the weakening organization and helped to professionalize it. Today, Wilayat Sinai is arguably the most developed branch of IS outside of the Syrian and Iraqi conflict zone. In terms of both its communications media output and operations, the group’s modus operandi is remarkably similar to the way IS operates at home. Its acquisition by the Islamic State has made it what it is today—a tightly organized group capable of inflicting damage in a largely lawless territory, using a logistical regional network that encompasses Libya, Sudan, Sinai, Gaza, and Syria.

Recent reports suggest increasing cooperation between Hamas and the Islamic State’s so-called Sinai Province. This cooperation culminated in a prolonged secret visit to Gaza in December 2015 by IS Sinai’s military chief Shadi al-Menai, who held talks with his counterparts in Hamas’s military wing, the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades (IDQB).

A Libyan Front?

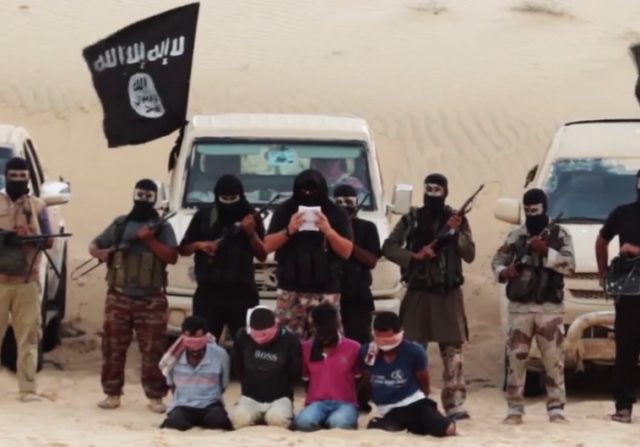

In February 2015, the Islamic State, having established itself in Derna, eastern Libya, in late 2014, released a disturbing video showing the beheading of 21 Egyptian Coptic Christian workers who had been kidnapped from Sirte, Libya, a year earlier. In retaliation, Egypt’s military carried out a series of air strikes against Islamic State militants in Libya. Other reports alleged that Egyptian Special Forces launched a ground attack in Derna, capturing dozens of Islamist militants. However, Egypt’s response to the IS threat near its western border was rather restrained, at least publicly.

Apart from Derna, the presence of IS on the Libya-Egypt border has not been proven. According to Mohamed Eljarh, a Libyan analyst and a nonresident fellow of the Atlantic Council, there is no evidence of the Islamic State’s presence on the Libya-Egypt border. However, there have been incidents in which IS militants were arrested in the desert areas south and east of Tobruk as they were heading toward Derna. As such, it would be safe to say that the ISIS story in eastern Libya is clearly far from over.

Further complicating matters for Egypt, in September 2015 the Islamic State announced its presence in Egypt’s Western Desert, and admitted its cadres clashed with the Egyptian army. A day after this alarming announcement, Egyptian Army aircraft hunting for militants in the desert accidentally bombed a convoy of Mexican tourists, killing 12 and wounding 10. The incident highlighted the inability of Egypt’s military establishment to protect its vulnerable 1,200-kilometer border with Libya.

Trade between the Western Egyptian Matrouh governorate and Libya has fallen by 80 percent due to unrest in the neighboring country and the frequent closure of the Salloum crossing, according to Matrouh tribal chief Beshir al-Obaidy. This, in turn, lays the foundation for further disorder, since economic depression has always helped militant groups both to survive and recruit.

Indeed, Libya has become Egypt’s new Achilles’ heel. The country’s failure to form a unified government, and the ongoing rivalry between various Libyan factions, makes Egypt’s task of securing its border much harder. While it is true that the Tobruk government in eastern Libya has allowed the Egyptian army to operate occasionally inside its territories, those operations are not sufficient to secure the common border. Egypt needs more sophisticated surveillance equipment and intelligence. The Mexican tourist incident not only highlighted the pitfalls of tackling the Western Desert, but also showed how tense and agitated the Egyptian army units are operating in the relatively new Western border theater.

Brotherhood under fire

These conditions to Egypt’s east and west have put increasing strain on the country’s now-ousted Islamist movement. The tenure of Mohamed Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated government saw a generally lax official approach to counterterrorism, raising questions about whether it had concluded some sort of deal with local militants. Even if it did, however, there were limits to this collusion, both then and now—in large part because the Islamic State and the Brotherhood are fundamentally at odds with one another. As Michael Horowitz of the Levantine Group explains, the Islamic State has dismissed the Brotherhood as a “secular project,” likely because the group accepted the “Western concept” of democracy.

The Muslim Brotherhood has historically maintained that it is a moderate, non-violent Islamist group, although Morsi’s ouster tested this proposition. Since its fall from political grace, the Brotherhood has been riven by widespread anger and deep political divisions. As a whole, the Brotherhood is now sharply divided and lacks a cohesive strategy to counter the government and stop young elements from joining more radical Islamist groups. According to Ahmed Rami, a spokesman for the Brotherhood-connected Freedom and Justice Party, since July 2013 the movement has been facing one of the deepest crises in its history—one that is both organizational and tactical.

This disorder has played into the hands of other Islamist groups. While Eric Trager of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy argues that there has been little evidence of younger Muslim Brotherhood members joining the Islamic State, at least so far, some Sinai tribal leaders fear that the death sentences issued against former President Mohamed Morsi and other Brotherhood members will push disaffected youth toward extremist groups now operating in the Sinai. Furthermore, al-Qaeda has tried to attract disenchanted Muslim Brotherhood members. Thus, in October 2015, Hisham Ashmawy, leader of the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Mourabitoun, released a video message calling on the youth of the Rabaa and Nahda Brotherhood camps, who had been forcibly evicted by Egyptian security forces, to join his group. He called on them to attack police and army ranks, but—unlike the tactics of the Islamic State—to do so within the boundaries of sharia (Islamic religious law).

An evolving response

Egypt’s government – and specifically its military, which serves as the principal instrument of official counterterrorism policy – has struggled to keep pace with this changing geopolitical landscape.

This is in part because the structure of Egypt’s armed forces has not changed significantly since 1968. The late Gamal Abdel Nasser formed the Second and Third Field Armies following Egypt’s defeat by Israel in 1967. The Second Field Army is based in Ismailia and is responsible for the northern part of the Suez Canal region. The Third Field Army is based in Suez and is responsible for the southern part of the Suez Canal region. Responsibility for Sinai, after its return to Egyptian sovereignty following the peace deal with Israel, was allocated to both the Second and Third Field Armies, with North Sinai under the former and the South under the latter. This geographical distribution has never been ideal for dealing with militants, who are not confined to a single location and have to use Sinai’s mountains and little villages as hideaway bases. Moreover, Sinai’s position as a buffer zone between Egypt and Israel, with its attendant restrictions on Egypt’s military presence in the Peninsula, has compounded the problem.

Egypt’s military solution to the increased jihadist activity in North Sinai was largely limited to setting larger and more numerous checkpoints along the narrow northern coastal highway. However, instead of quelling militancy, this tactic exposed army ranks in those checkpoints to ambushes. In addition, militants regularly planted roadside bombs targeting army patrols and reinforcements from Cairo.

The military establishment then opted to launch massive military operations to restore order in North Sinai and confront Islamist militants, For example, in 2011, the army launched a large-scale hunt for militants under the name Operation Eagle. In 2012, a similar operation, Operation Sinai, was launched, during which the army started to destroy tunnels under the border with Gaza, with the aim of cutting weapons smuggling and the movement of jihadis across the border. Since then, the systematic destruction of tunnels and the hunting down and killing of senior ABM militant cadres has continued. However, all of the above measures have had little impact on the group’s ability to launch deadly attacks.

Things are beginning to change, though. In early 2015, major attacks by militants killed at least 27 people, mostly soldiers. In response, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi made two important decisions. He established a unified military command east of the Suez Canal, tasked with fighting radical groups in the Sinai Peninsula. He also pledged $1.3 billion to develop the impoverished area. Both decisions indicated a major shift in Egypt’s military leadership away from its de facto mind-set of fighting conventional wars. It also showed Egypt’s readjustment to the evolving reality of a growing insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula.

This military reshuffle has been matched by other measures. Since taking office, President Sisi has approved a stringent anti-terrorism law that sets special courts and details sentences for various terrorism crimes, ranging from five years to the death penalty. He has also tried to address the ideological background of jihadism, most prominently in a January 2015 address to Islamic scholars at al-Azhar University in which Sisi called for a “revolution” in Islam to reform interpretations of the faith.

The outcome of these steps, however, is far from certain. Despite recent losses, the Islamic State is still keen to prove its viability. In October 2015, militants kidnapped three pro-government tribal fighters manning a checkpoint in Sinai. Eleven police conscripts were injured in a blast that targeted a tank in North Sinai’s Arish. In Cairo, IS claimed it had planted a car bomb at an intersection near the pyramids. In response, Egypt has extended by three months a state of emergency imposed on parts of Northern Sinai.

Ideologically, meanwhile, the government has encountered significant resistance among al-Azhar scholars to the reform of Islamic thought, despite Sisi’s repeated entreaties to tackle the issue. al-Azhar even pressed charges against reformist Islamic researcher Islam Beheiry, accusing him of insulting religion. Later, a Cairo court sentenced Beheiry to five years in prison for insulting Islam.

More to come

Neither terrorism nor the dream of a medieval-style Islamic state is new to Egypt. What is new today, however, are the changes in both local and regional conditions that have complicated and in many case frustrated Egypt’s counterterrorism efforts. The terrorist groups active against the Egyptian state today are fueled by a lethal triangle of factors: a disenfranchised periphery, divided (and divisive) national politics, and increasingly angry Islamist youth. This trio of causes virtually guarantees that Egypt’s cycle of terror will continue for the foreseeable future.

Nervana Mahmoud, MD, is a British-Egyptian doctor and commentator on Middle East issues. A version of this article appeared in the Journal of International Security Affairs and is reprinted with the permission of JINSA.