Iraqis went to the polls on Saturday to pick new parliamentary representatives from a list of 7,376 candidates for 328 seats. Preliminary results suggest that a movement led by Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, a long time critic of the U.S. presence in the Middle East, will win 55 seats. Sadr’s gains come at the expense of two pro-Iranian establishment parties currently in power, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s Victory Alliance and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki State of Law coalition.

Of the more than 22 million registered voters in Iraq, only about 45 percent participated, down substantially since elections in 2014 and 2010. Interviews with local Iraqi voters indicated that some felt contempt for what they perceived as a tired pool of political leaders and rampant government corruption. Meanwhile, other Iraqis displaced during the war with Islamic State, such as those living in Mosul and U.N. camps in Anbar province, expressed other priorities. Many outside of central Iraq feel isolated from a political system centered in Baghdad and that politicians are indifferent to their struggles.

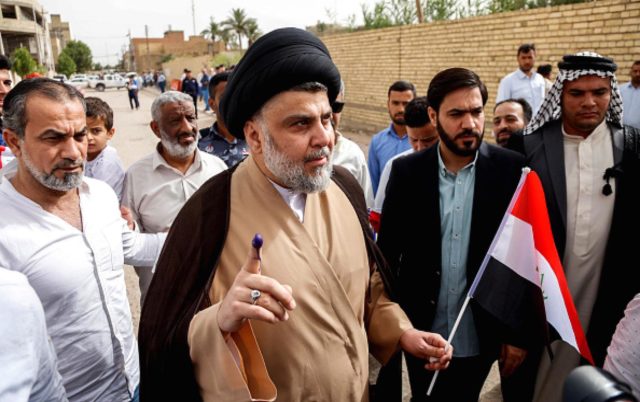

Even though he was not a candidate himself, Moqtada al-Sadr’s political movement, known as the Alliance of Revolutionaries for Reform, took advantage of this discontent and launched a multi-sectarian campaign based on anti-corruption. Some Sunni businessmen and local small communist groups even voiced support for his movement. According to a spokesman for Sadr’s party cited in The New York Times, the group is now looking for partners to achieve three main objectives, “ending the practice of awarding ministries on sectarian quotas, fighting corruption and allowing independent technocrats to manage key government agencies.”

While Sadr’s movement might advocate responsible government, the cleric has long opposed U.S. interests in Iraq. Between 2004-2008 U.S. troops fought Sadr’s Mahdi Army, with a standing order to kill or capture him. The Pentagon considered the militia “the most dangerous accelerant” for fomenting sectarian violence. Eventually, Iraq’s top Shiite cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani helped broker a deal whereby Sadr would temporarily relocate to Iran.

In 2011, Sadr returned to Najaf, Iraq and attempted to recast his image. The cleric has selectively voiced support for some Sunni activists who opposed then-Prime Minister Maliki. Since then, he has threatened U.S. troops in Iraq fighting IS but has also distanced himself from Iran, which he also complained about meddled in Iraq’s affairs. As Iraq enters post-IS politics, Sadr’s nationalism provides new vigor to counter corruption and Iranian-backed militias, if it does not revert to sectarianism first.