Within hours of suffering chest pains in early October, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders had stents inserted to relieve the blockage in an artery. He’s lucky. Because if Sanders lived under “Medicare for All,” things likely would not have gone as well.

Sanders, along with every other Democrat pushing “Medicare for All” and its variants, constantly bleats about how the US spends far more on health care but gets worse results than countries such as Canada or the UK But the quality measures – infant mortality and longevity – are notoriously unreliable for international comparisons.

Infant mortality rates depend on how countries measure them, and longevity has more to do with things like obesity, crime, and drug abuse than health care.

What Sanders and company never do is look at how countries handle actual health care delivery. That’s because when you do that, socialized medicine starts to look more like Hell than Nirvana.

Canada and the UK are plagued with chronic shortages of doctors and nurses, shortages of hospital beds, shortages of the latest diagnostic tools.

The result is treatment delays and outright denials. This grim reality plays out daily in the newspapers of the two countries, stories that Sanders, Sen. Elizabeth Warren and other single-payer advocates pretend don’t exist.

This is as true for heart patients as anyone else.

A 1995 study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology found that no patients needing an urgent coronary angiography test – used to reveal artery blockages – received one within 24 hours in Canada or the UK, whereas 65 percent did in the United States Nearly two-thirds of Canadians and 94 percent of Brits had to wait more than three days.

The same study found that while 80 percent of urgent coronary bypass operations occurred within 24 hours in the US, only 24 percent did in Canada and 10 percent in the UK.

The situation has not improved in either country since then. A dozen cardiac patients died in Quebec in just the first four months of this year while waiting for surgery. Why the delay? According to the head of the province’s cardiac surgeons association, it’s largely because “of a shortage of operating room nurses and perfusionists – the technicians who operate the heart-lung machine during the surgery” as well as a lack of hospital beds.

Overall wait times for specialist care of any kind has more than doubled in Canada since the 1990s, according to the Fraser Institute, which has been tracking this.

The British regularly see headlines such as “Heath patients die on waiting lists,” and “Patients are dying waiting for heart surgery.” In Wales, 152 patients died waiting for heart surgery in two hospitals over five years. Last year, the NHS reported that wait times for bypass surgery doubled in Wales to 79 days.

A 2003 analysis found that the death rate for patients with congestive heart failure was three times higher in British hospitals than those in the Unted States.

Heart patients are hardly the only ones forced to wait for treatments in those countries. In the UK, shortages of doctors and nurses often force cancer patients to wait so long that their survival rates are now lower than comparable countries, and far below survival rates in the United States.

Tens of thousands of Canadians come across the border each year and pay out of pocket for health care they can’t get in a timely fashion from their country’s version of “Medicare for All.”

This could go on, and on, and on. The point is that these problems would inevitably emerge here if politicians and companies were allowed to impose “Medicare for All” on the country. Socialism always leads to shortages and lower quality.

It is good that Sanders got the care he needed in a timely fashion and hope for a speedy recovery. We just wish he’d embrace the (mostly) private health care system that provided him such excellent care, instead of trying to destroy it with “Medicare for All.”

Thinking about Health Care

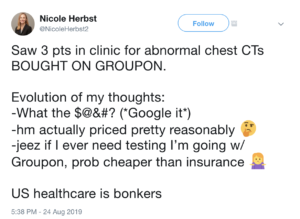

During the fall, a medical fellow at Emory University posted a tweet after three patients came in with Groupon coupons for chest CT scans.

In the space of one Twitter post, she goes from shock that anyone would use a coupon for a medical test, to realizing the patients got a really good deal, and that the cost was likely less than it would have been had they used insurance.

Bonkers is right. But not for the reason Dr. Nicole Herbst probably thinks.

Bonkers is right. But not for the reason Dr. Nicole Herbst probably thinks.

What’s bonkers about the nation’s health care system isn’t that some people are using coupons for medical tests. What’s bonkers is that the practice is so rare.

In what other corner of life – other than health care – would anyone be surprised to learn that consumers are shopping around? People shop around for other necessities, such as food, water, and shelter. Why not health care?

After her shock wears off, even Dr. Herbst realizes that the patients coming in with Groupon coupons were getting really good deals. Indeed, they are. A patient in Oklahoma City can use Groupon to get a heart scan – which would normally cost $640 – for just $54. In Atlanta, a heart scan with a consultation is just $25.

Dr. Herbst even comes to realize that using Groupon could be “cheaper than insurance.”

Yet having to pay for health care is routinely treated as a moral failing of the country – even if it’s just to see a doctor, or get an x-ray, or fill a $20 prescription.

CNBC ran a story in October bemoaning the fact that people sometimes put off seeing a doctor to save money, with the scary headline, “High medical costs have driven these people to put their health at risk.”

What was the crisis? That a third of those surveyed said they had at some point in the past “delayed seeking medical help with hopes the condition will subside.” It also found that 27 percent had “considered” not seeking care to “avoid high deductibles.”

That’s hardly a problem, let alone a crisis. A large portion of those who saved money by putting off seeing a doctor probably did see their conditions subside. And “considering” not seeking care is different from actually not seeking care.

But what apparently hasn’t occurred to Dr. Herbst, or the reporters and editors at CNBC, or most health care “experts,” is to ask the question: Why is shopping around for health care so rare? The survey cited by that CNBC article notes that only 27 percent said they’d ever shopped around for a better price on prescription drugs.

The Culture of Health Care Spending

Had any of these folks bothered to explore this question, they’d learn that massive federal subsidies created a culture in which people who willingly shell out $10 for a cup of coffee feel aggrieved about paying anything at all to get a medical test.

It wasn’t always like this. In 1960, half of the nation’s medical bills were paid out of pocket. Outside of hospital visits, insurance didn’t cover routine care. Patients paid doctors in cash for checkups and routine tests.

Today, only 10 percent of health costs are paid directly by consumers buying products or services. That share is expected to steadily decline.

Why the dramatic shift? First was the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, which now pick up most if not all medical costs for seniors and the poor. These two programs alone account for 37 percent of all health spending.

Federal tax policy accounts for much of the rest of the shift away from out-of-pocket spending. Under current law – which is an artifact of World War II-era wage and price controls – the entire cost of employee health care benefits is exempt from taxes. This amounts to a $280 billion annual subsidy for employer-provided health insurance.

As a result, health bills paid by employer plans are tax exempt. But any care paid for out of pocket had to use after-tax dollars. Is it any surprise that employer plans got increasingly generous, covering even routine bills?

Is it any surprise, either, that consumers lost interest in shopping around? Why bother, if the government or an insurance company ends up being the main beneficiary of their frugality?

It’s worth noting that at 10 percent, the out-of-pocket share of health spending is lower in the US than in almost every other country that has declared medical care a “right” and promises “universal coverage.”

In Finland, they pay 20 percent of health care costs out of pocket. The Swedes and Norwegians pay 15 percent. In Denmark, it’s 14 percent. Canadians pay 15 percent of their health costs out of pocket. Even in communist China, people have to pay more than 30 percent of health costs out of pocket.

What’s needed isn’t less out-of-pocket spending for health care, but more of it. In every other part of the market, choice and competition drive down prices and increase quality. The same would work in health care, if government policies would stop discouraging it.

When doctors’ offices are full of Groupon-wielding patients, the health care system will no longer be “bonkers.” It will be reformed.

John Merline is Editor of Issues & Insights, from which this article is adapted. He is a former Deputy Editor of Commentary and Opinion at Investor’s Business Daily, and editor of the Opinion section of AOL News.