Generalizing about blacks and anti-Semitism is a mistake.

The presence of African-American community leaders and politicians at the January 5, 2020 New York City march against anti-Semitism was heartening. So, too, are the many testimonies that have come forward from individuals about acts of caring and kindness towards the ultra-Orthodox community that has been targeted for violence from many of their African-American neighbors. Those who would treat this as a conflict between two communities that are locked in an existential struggle are wrong.

Yet the history of black-Jewish relations, especially in New York City over the last half century, is complicated. While they might have once seemed like two minority communities that were natural allies in the struggle for civil rights, blacks and Jews also found themselves on the opposite sides of many issues in the 1960s and its aftermath. And the anti-Semitism of many leading black activists in the 1960s during conflicts over housing, the education system and other disputes was a distressing development.

The tensions between poor blacks and the ultra-Orthodox Jews who remained in Brooklyn neighborhoods that other Jews fled might have created misunderstandings on both sides. But the Crown Heights riots of 1991 that activists such as the Rev. Al Sharpton helped incite, in which a 29-year-old Orthodox Jewish student from Australia was murdered and many others injured, was part of this legacy. The fact remains that surveys over the last quarter century have consistently shown that African-Americans hold anti-Semitic views at a rate far higher than the rest of the population. Twenty years after Crown Heights, an Anti-Defamation League survey showed that 29 percent expressed “strongly anti-Semitic views.”

That problem has grown worse as black activists have embraced false intersectional theories that view Jews and Israel on the other side of an intractable divide between oppressors and “people of color” even though the majority of Israelis can be described by the same phrase. There is nothing remotely in common between the struggle for civil rights in this country and the Palestinian war to destroy the only Jewish state on the planet.

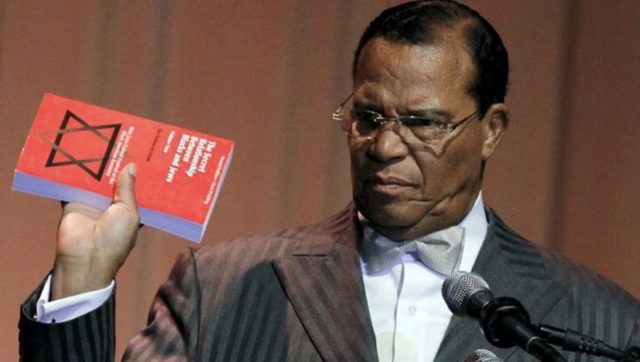

Nor can the influence of hate-mongers like Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, a group that has far more active followers and sympathizers than any white-supremacist group, be denied.

Many in the Jewish community prefer to downplay these factors because they don’t fit into their preferred narrative about anti-Semitism. Others, like the Reform movement of Judaism, think the problem is Jewish racism, as Rabbi Jonah Pesner stated when successfully urging the denomination to support reparations for the descendants of African-American slaves. Such sentiments meld with those who prefer to blame the victims of the violence and see attacks on Jews as a natural reaction to gentrification or economic exploitation of blacks.

These fallacious arguments are sometimes rooted in the prejudicial attitudes many secular and non-Orthodox Jews have about the ultra-Orthodox. Nor is it out of line or racist to ask more African-American leaders to be outspoken in denouncing anti-Semitism in their communities and encourage programs, such as those promoted by the ADL, which will help young blacks see through the lies told by the Jew-haters.

Yet as much as we must resist the impulse to avoid criticizing black anti-Semitism because of black’s long history of oppression, the opposite is also true. It is equally important for those calling attention to black anti-Semitism to realize that Jews and blacks are not competing for victim status. Nor is it helpful or accurate to assume that minority communities are invariably hostile, or that common ground can’t still be found. This discussion can be derailed by insensitive or needlessly inflammatory rhetoric, even if the motives of those speaking out on the issue are not racist. How we discuss the reality of black anti-Semitism is as important as our willingness to acknowledge it.

Jonathan S. Tobin is editor in chief of JNS—Jewish News Syndicate.