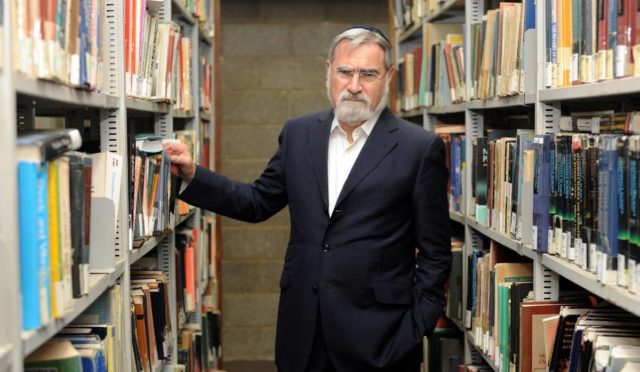

The Jewish Policy Center mourns the passing of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, chief rabbi of the UK from 1991 to 2013, and a member of the House of Lords from 2009. His academic credentials were impeccable and his intellect towering, but the respect he has been accorded in the UK, Israel, and the United States owed at least as much to his gentle personality and his ability to infuse broad knowledge with deep humanity. Rabbi Sacks was, as well, a student of the United States and had an abiding love and respect for America, its Founding Fathers, its Constitution, and its history.

May his memory be a blessing for his family, his students (which would be all of us), his country, and the Jewish people.

Below is an excerpt from his speech delivered in 2017 at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. It will, no doubt, inspire you to read more and learn more from late, and very much to be missed, Rabbi Sacks.

“We Hold These Truths to be Self-Evident”

What makes the Hebrew Bible unique and really fascinating and makes it completely different from Hobbes and Locke and Jean-Jacque Rousseau is that [the anointing of King Saul] wasn’t the first founding moment of Israel as a nation, as a political entity. It was in fact the second because the first took place centuries earlier in the days of Moses at Mount Sinai when the people made with God not a contract but a covenant. And those two things are often confused, but actually they’re quite different.

In a contract, two or more people come together to make an exchange. You pay your plumber – I have a Jewish friend in Jerusalem who calls his plumber Messiah. Why? Because we await him daily, and he never turns up. So, in a contract, you make an exchange, which is to the benefit of the self-interest of each. And so, you have the commercial contract that creates the market and the social contract that creates the state.

A covenant isn’t like that. It’s more like a marriage than an exchange. In a covenant, two or more parties each respecting the dignity and integrity of the other come together in a bond of loyalty and trust to do together what neither can do alone. A covenant isn’t about me. It’s about us. A covenant isn’t about interests. It’s about identity. A covenant isn’t about me, the voter, or me, the consumer, but about all of us together. Or in that lovely key phrase of American politics, it’s about “We, the People.”

The market is about the creation and distribution of wealth. The state is about the creation and distribution of power. But a covenant is about neither wealth nor power, but about the bonds of belonging and of collective responsibility. And to put it as simply as I can, the social contract creates a state, but the social covenant creates a society. That is the difference. They’re different things.

Biblical Israel had a society long before it had a state, before it even crossed the Jordan and enter the land, which explains why Jews were able to keep their identity for 2,000 years in exile and dispersion because although they’d lost their state, they still had their society. Although they’d lost their contract, they still had their covenant. And there is only one nation known to me that had the same dual founding as biblical Israel, and that is the United States of America which has – (applause) – which had its social covenant in the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and its social contract in the Constitution in 1787.

And the reason it did so is because the founders of this country had the Hebrew Bible engraved on their hearts. Covenant is central to the Mayflower Compact of 1620. It is central to the speech of John Winthrop aboard the Arbela in 1630. It is presupposed in the most famous line of the Declaration of Independence.

Listen to the sentence. See how odd it might sound to anyone but an American. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights.” Those truths are anything but self-evident. They would have been unintelligible to Plato, to Aristotle, or to every hierarchical society the world has ever known. They are self-evident only to people, to Jews and Christians, who have internalized the Hebrew Bible. And that is what made G. K. Chesterton call America “a nation with the soul of a church.”