If 2020 was, in the memorable words of Queen Elizabeth II, “annus horribilis,” then Supreme Disorder by Ilya Shapiro is a book for 2021. This fascinating history of the Supreme Court and its Justices, and thoughtful exposition of the current and possible future shape of the Court, and the nature of its controversies through the years, would have been a tough read in 2020. Now, take a deep breath and consider some of the basic assumptions we Americans make about our country and our institutions.

If 2020 was, in the memorable words of Queen Elizabeth II, “annus horribilis,” then Supreme Disorder by Ilya Shapiro is a book for 2021. This fascinating history of the Supreme Court and its Justices, and thoughtful exposition of the current and possible future shape of the Court, and the nature of its controversies through the years, would have been a tough read in 2020. Now, take a deep breath and consider some of the basic assumptions we Americans make about our country and our institutions.

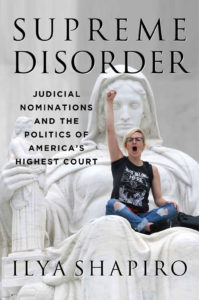

Shapiro is Director of the Robert A. Levy Center for Constitutional Studies at the Cato Institute, and publisher of the Cato Supreme Court Review, and a member of the Jewish Policy Center Board of Fellows. His affiliations tell you a lot about how he sees the Court, and his fluid writing makes a sometimes-arcane subject – Buck v. Bell or Lochner v. New York and the ever-popular Lawrence v. Texas – easily digestible. The two attributes create a thought-provoking book.

There will be a temptation to skip the history and read the chapters “What Have we Learned?” “Term Limits,” “More Radical Reforms,” “A Question of Legitimacy,” and the “Conclusion” first. A temptation to delve into the fundamental questions: “What is the Supreme Court for?” “Do we need one?” “If we do, can it be disconnected from our current politicized atmosphere?” “Should it be disconnected? Maybe the world is truly a different place in the 21st century and the old job of the Court is no longer relevant.”

But don’t give in to temptation.

History First

Precisely because 2020 has left us literally breathless, and perhaps thinking we’ve never been such a mess before, read the history. We have been. And the Court has played a key role – both positive and negative (see the section on Justice Roger Taney and Dred Scott) in the development and maturation of the United States and its federalist system.

Learn about the Founding Fathers’ intentions for the Court and the able and less able men (until the modern era) who sat on it. The size of the court changed in the first decades, but the current nine-member configuration is 150 years old, despite the hopes of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and, perhaps, modern Democrats.

The Founders weren’t certain there should be a Supreme Court (see Young Patriots, reviewed in inFOCUS Quarterly, Fall 2000), but Justices John Marshall and Joseph Story used the early Court to unite the States under a uniform system of laws based on “property rights and free interstate commerce.” They were Founding Fathers as certainly as Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. Jefferson, by the way, worried about expanding the Court for fear that it would concentrate too much power in Washington at the expense of the States. By Andrew Jackson’s administration, however, the Court was “enshrined in the Federal Government” and turned its attention to politics – for the first time, but not the last.

The section on the run up to the Civil War, and the war itself is a reminder that our country has faced not only division but deadly division over the hideous institution of slavery.

One reason so few people paid attention to who was on the Court and what the Justices believed was that, through Reconstruction up until the New Deal, legislators legislated and the Supreme Court measured legislation against the Constitution. It is also true, of course, that the advent of media – and now social media – has brought citizens across the country into the halls of power, peeking under the table and over the shoulders of powerbrokers. This creates an apparently irresistible temptation for politicians to become actors, and journalists to become “media personalities.”

Under those circumstances, the selection and vote for a nominee becomes an event in a way it never had been before. And Justices are now understood to sit on the Court to advance policy – the policy of the political party that appoints them. The politician’s temptation becomes planning on a Justice making policy for the country, instead of evaluating the constitutionality of measures enacted by the legislative branch and signed into law by the Executive.

It also allows Congress to evade its responsibilities by writing broad outlines of law, then commanding the Executive Branch to write policy rules and regulations, when Congress should write laws, not hopes and dreams.

Therein lies the problem, according to Shapiro.

Where is the Court Going?

The inflection point for our legal culture, as for our social and political culture, was 1968, which ended that seventy-year-near-perfect run of nominations. Until that point, most justices were confirmed by voice vote, without having to take a roll call. Since then, there hasn’t been a single voice vote, not even for the five justices confirmed unanimously or the four whose no votes were in the single digits.

The Court is now “part of the same toxic cloud that has enveloped all of the nation’s public discourse.”

While Democrats during the recent election have talked about “court packing,” there have been a number of suggestions proffered by the left and the right – and even a few by people who claim non-partisanship and wish the Court could claim as much for itself – in an effort to “save the Court.”

Posited changes to the Court include term limits for justices (noting that as longevity has increased, Justices who are nominated in their 40s could expect to serve for 40 years); adding more justices; restructuring the court through the use of a “lottery” system that would move more justices through the system; and “a “balanced court” that would have 15 members – Five Democratic and five Republican-affiliated justices , plus 5 others who would have to be “selected unanimously by the partisan justices.”

But all of these responses appear to address the current unhappiness with the Court – which is the unhappiness of liberal lawyers and politicians. Shapiro writes,

Underlying both the ‘judicial lottery’ and ‘balanced court’ proposal is a problem with the proponents’ premise, that the Court needs saving in the first place. The Court isn’t in crisis, but liberals – and especially legal elites, who have relied on it to solve social ills they can’t remedy at the ballot box – are very unhappy with its nascent conservative majority. For (certain legal voices) the court’s legitimacy means the sociological acceptance of the Court’s role, but…the Court is more popular than other government institutions.

And that was before Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the court.

The question of the court’s legitimacy is primarily one posed by progressives – who have seen the addition of Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh (and ACB, although Shapiro didn’t know it then).

The background insinuation is clear: if the justices rule in ways that disagree with progressive orthodoxy, there will be hell to pay. The morning of last term’s big abortion case, June Medical Services v. Russo, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said before a cheering crowd on the courthouse steps, “I want to tell you Gorsuch. I want to tell you, Kavanaugh. You have released the whirlwind, and you will pay the price.” The NY Democrat added, “You won’t know what hit you if you go forward with these awful decisions.”

The threat was so direct that Chief Justice John Robert issued a press release, decrying “threatening statements of this sort from the highest levels of government are not only inappropriate, they are dangerous.”

The irony of Schumer’s polemic, which Shapiro likens to a mafia threat, “nice little Court you have there… shame if something happened to it,” – is that it isn’t the Court that has failed the American people. The problem is that the Court is presently filling in for the inability of Congress to legislate.

Congress and the presidency have gradually taken more power for themselves and the Supreme Court has allowed them to get away with it, aggrandizing itself in the process. As the Court has let both the legislative and executive branches swell beyond their constitutionally authorized powers, so have the law and regulations that it now interprets.”

Competing theories battle for control of both the U.S. Code and Federal Register, as well as determine – often at the whim of one ‘swing vote’ – what rights will be recognized.

The Cure

President Abraham Lincoln was both timely and prescient in 1861, when he said, “If the policy of the government upon vital questions…is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court… the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.”

Shapiro concurs:

The only lasting solution…is to return to the Founders’ Constitution by rebalancing and devolving power, so Washington isn’t making so many big decisions for the whole country. Depoliticizing the judiciary and toning down our confirmation process is a laudable goal, but that’ll happen only when judges go back to judging rather than bending over backwards to ratify the constitutional abuses of the other branches.

Which makes a very good opening to 2021. Shapiro doesn’t tell us how to restore bipartisanship or depoliticize the judiciary; that is for We the People to demand of those we place in the Executive and Legislative Branches, and thus allow the Judiciary to return to its former, quieter, but no less vital role.