Miami is a boom town, with not much sign of the pain of COVID other than some mask wearers. The schools have been open since August, the shops, restaurants, bars are open, albeit with some distance spacing. Both the State and the City of Miami governments are running budget surpluses. New construction is everywhere. Realtors complain about the lack of housing inventory, as a flood of people from New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, etc. flee those disasters to come to “paradise.”

Florida is benefitting from the incompetence and destructive policies of the poorly managed states. Florida has no state income tax, but despite having a larger population than New York gets along just fine on about half of the revenue. Unfortunately, not even Florida is going to be able to escape the policy disasters of the Biden Administration and the Congress.

Over the last year, many businesses have learned they do not need lots of expensive floor space in Manhattan’s luxury office buildings to operate perfectly well. Some businesses have moved, or will shortly move to Florida and elsewhere, and so it may be many years before Manhattan office space is fully occupied. The workers that filled those offices have left or will leave, so many of the apartments in the city are going to remain vacant. The restaurants and shops that catered to all of the workers and residents will see a long-term drop in demand. The financial institutions that depended on the mortgage cash flow from the offices, shops and residences will be faced with a high level of defaults, which in turn will cause them to default or scale back. These financial failures will spread outside of New York, and eventually cascade throughout the economy. The drop in New York rental income will cause prices to drop. Rents and real estate prices are rising in Florida so what appears to be inflation in the Florida market will partially offset the price drops in New York.

Most measures of human activity get better over time, but not inflation numbers – more on this below. Inflation is said to be a result of the money supply growing faster than the supply of goods and services – which is true provided the velocity (the number of times the money turns over) of money does not change. Last year the money supply grew at a record level – more than 25 percent – but it did not result in immediate inflation because most of it was not spent. Instead, people and businesses greatly increased their savings, causing a decline in the velocity of money.

Most major governments ran enormous deficits this past year, and many already had record high levels of debt, as can be seen in the accompanying table. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve bought much of the new debt from the banks, which bought it from the Treasury – but then the Fed left most of the funds from the sale with the banks, as bank reserves. The result of all these convoluted actions was to lock up the “new money” so no inflation resulted. This shell game cannot continue and as the economy recovers and the banks increase their lending, inflationary pressures will rise.

Deficits & Debt

Economists define inflation as a general increase in the price level where the purchasing power of the money declines. But as previously noted, in the real world some prices increase while others fall. The government has many measures of inflation, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) being the best known. Economists frequently use Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) in the belief that it gives a slightly better measure of real inflation.

The government tries to measure changes in prices over time for hundreds of different goods and services. Some things are easy to measure – such as the price of a bushel of wheat or corn – where the records of free-market determined prices have existed for these products for well over two centuries, and the nature of the product has changed only very slowly. And at the other end of the spectrum are totally new products that replace many other previously produced goods and services, notably the smartphone.

Only a couple of decades ago, transAtlantic phone calls could cost several dollars a minute. Now, the marginal costs of such calls, depending on the device and communication plan, can cost close to zero – a massive deflation in communications’ costs. Two decades ago, most people had film cameras which required the purchase of film and then a trip to the store to get the pictures developed – which involved significant costs. Now everyone has far better cameras in their phones, where the pictures cost zero to take and send to others. Which means that the purchasing power of dollars spent on photography has soared (huge deflation).

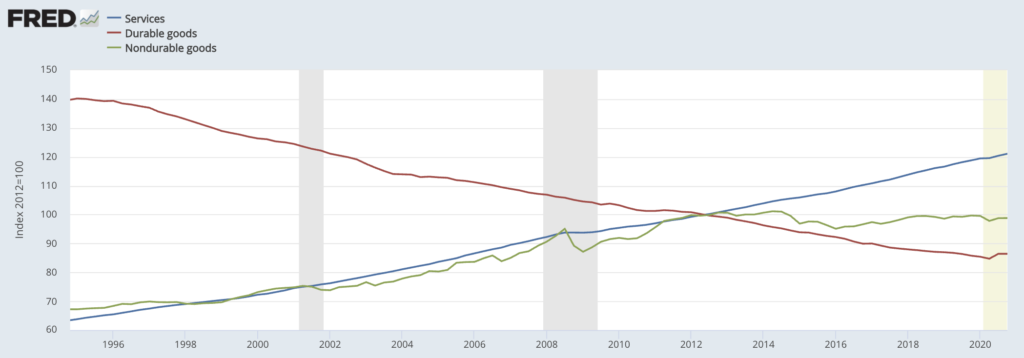

In trying to measure inflation and deflation, government statisticians attempt to determine what people spend for durable goods – those that last more than three years (such as automobiles, furniture, appliances, aircraft, etc.); non-durable goods that are consumed in less than three years (such as food, gasoline, paper, etc.); and services (such as banking and other financial services, maintenance or repair work, transportation, legal services, etc.). The above chart shows the relative price of average durables has declined for the past twenty-five years (by about 38 percent). (The statisticians attempt to factor in product improvement in their price calculations – such as new safety features in automobiles – which is a most difficult task.) The price declines have been driven by technological progress, including manufacturing efficiency improvements, and the “China effect” whereby much manufacturing was transferred to China and other low-wage countries, enabling Americans to buy many things less expensively. These goods were often sold in Walmart and other highly efficient retailers that could cut margins and prices at great benefit to consumers – making their dollars in effect worth more (deflation).

During this same 25-year period, the price of non-durable goods rose at about 46 percent. Virtually all of this price rise occurred before 2012, while in the last eight years many prices fell. The fracking revolution reduced the real price of gasoline and natural gas, and huge productivity gains in agriculture continued. Also, deregulation under the Trump Administration allowed for many production efficiencies, again reducing prices.

Unfortunately, the Biden Administration is reversing course, and its policies are likely to cause the price of energy and many other goods and services to increase. As the restrictions from the pandemic are lessened, temporary supply shortages will arise, again causing price increases. For instance, there is a shortage of cargo containers because, as ocean shipping recovers from the shutdown, the demand for containers has soared. This has led to large increases in shipping costs that are, in turn, passed along to the cost of the goods being shipped and, ultimately, higher consumer prices.

Service costs have risen most rapidly (about 86 percent in the last 25 years) – in part because productivity gains have been so much lower in the service sector than in the goods sector. Medical and educational services are major components of the services price indices. As measured by student achievement and costs per student, most education has shown negative productivity gain – that is, it costs more today in real terms to achieve reading and math proficiency in the average student than it did a quarter of a century ago.

There have been enormous gains in medical science, but these gains have been offset by the ever growing medical and paperwork bureaucracy. Tens of millions now have most of their health bills paid in part by Medicare, Medicaid, the VA, and other government health insurance and so have little or no idea of how much any given medical procedure costs – and hence are insensitive to the price. As the medical price system has broken down, the ability to measure medical cost inflation has become nearly impossible.

The result is that the house of cards that has been created is going to fall. But no one knows precisely when – next week, next month or next year. Those old enough to remember the late 1970’s will recall they were not pleasant times – with soaring inflation and after-tax incomes rising more slowly than prices.

Over the last eight years, the Greeks have gone through something similar. They engaged in more deficit spending than they could support, and finally no government or company would lend them more money. The result was they had to lower their consumption to what they were actually producing – so living standards have dropped on average by more than thirty percent. Much of the rest of the world is going to experience something similar, including the U.S. People may protest or riot, but there is no painless way out of reality.

Richard W. Rahn is chairman of the Institute for Global Economic Growth and MCon LLC.