The Biden Administration’s national security strategy, as released to the public at the end of 2022, has some praiseworthy elements, stressing, for example, the “need for American leadership.” But it does not take its own words seriously enough. Its discussion of “leadership” is confusing, and the administration is not providing for the kind of military strength that would make US leadership effective.

A Word on Precision

A strategy should not use vague and ambiguous language (let alone mind-numbing repetition). Having said that no nation is better positioned than the United States to compete in shaping the world, as long as we work with others who share our vision, the strategy declares (the italics are mine), “This means that the foundational principles of self-determination, territorial integrity, and political independence must be respected, international institutions must be strengthened, countries must be free to determine their own foreign policy choices, information must be allowed to flow freely, universal human rights must be upheld, and the global economy must operate on a level playing field and provide opportunity for all.” The fuzziness — incoherence — of using the word “must” should be obvious.

For example: “The United States must . . . increase international cooperation on shared challenges even in an age of greater inter-state competition.” But “some in Beijing” insist that a prerequisite for cooperation is a set of “concessions on unrelated issues” that the US government has said are unacceptable. So, the strategy effectively declares that cooperation with China is a “must” even when China says we cannot have it. In other words, the word “must” doesn’t really mean “must.” In this case, it expresses no more than the administration’s impotent preference.

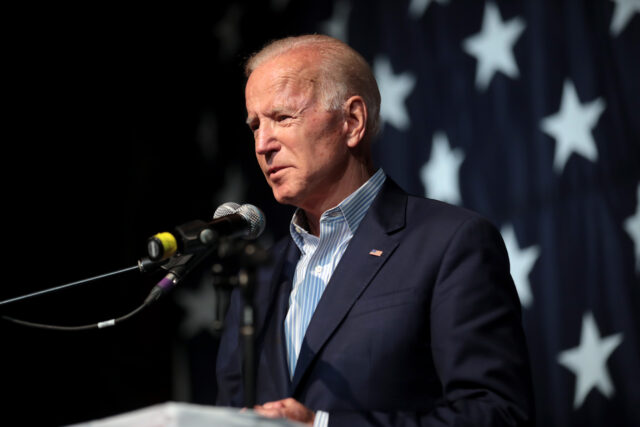

This strategy is 48 pages long. It uses the word “must” 39 times. To drive home that President Joe Biden is not his predecessor, the strategy constantly emphasizes allies and partners. It uses the word “allies” 38 times and “partner” or “partnership” an astounding 167 times. Meanwhile, it does not use “enemy” even once. Two of the three times it uses the word “adversary” it is referring to “potential” rather than actual adversaries. The third time, it says only that America’s network of allies and partners is “the envy of our adversaries.”

Enemies and Hostile Ideology

The strategy identifies, correctly in my view, America’s “most pressing challenges” as China and Russia. China is described as the only “competitor” with both the intent and power to “reshape the international order.” Russia is called “an immediate threat to the free and open international system,” while the Ukraine war is rightly characterized as “brutal and unprovoked.” The discussion of enemies, however, is euphemistic and misleading and does not give explicit guidance on confronting them. Alluding to China and Russia, it talks of “competing with major autocratic powers” as if everyone in the “competition” is playing a gentlemanly game with agreed rules. That creates a false picture of the problem.

The strategy states that China “retains common interests” with the United States “because of various interdependencies on climate, economics and public health.” In discussing “shared challenges”—such as climate change or COVID—it implies that Chinese leaders see these challenges the same way the administration does, but the well-known recent history of Chinese secretiveness about COVID, for example, refutes that assumption.

There are references to pragmatic problem-solving “based on shared interests” with countries like China and Iran. The strategy does not explain, however, what US officials should do if such cooperation is inconsistent with other US interests. Should they work with China at the expense of opposition to genocide against the Uyghurs? Should they work with Iran at the expense of that country’s pro-democracy resistance movement?

Iran and North Korea are called “autocratic powers,” but being autocratic is not the key to their hostility and danger. Rather, it is that they are ideologically hostile to the United States and the West.

There are two passing references to “violent extremism,” though no discussion whatever about anti-Western ideologies. US officials are given no direction to take action to counter such ideologies. The strategy is entirely silent on jihadism and extremist Islam.

Ties to Allies and Partners

While it properly calls attention to the value of America’s “unmatched network of alliances and partnerships,” the strategy does not deal adequately with questions of when the United States should lead rather than simply join its allies. It does not acknowledge that there may be cases when the United States is required to go it alone. President Biden is quoted as telling the United Nations, “[We] will lead. … But we will not go it alone. We will lead together with our Allies and partners.” But what if American and allied officials disagree? Sometimes the only way to lead is to show that one is willing to go it alone.

Failing to distinguish between leadership and followership is a major flaw. While asserting that America aspires to the former, the strategy declares that “we will work in lockstep with our allies.” Such lockstep would ensure that the United States is constrained by the lower-common-denominator policy of our allies. If President Biden really believes what he is saying here, he is telling his team to refrain from initiatives that any or all of our allies might reject. Instead of soliciting ideas from administration officials that would serve the US interest even if they require campaigns to try (perhaps unsuccessfully) to persuade our allies to acquiesce, his strategy discourages initiative and efforts to persuade. That is the opposite of leadership.

The strategy says that “our alliances and partnerships around the world are our most important strategic asset.” But that is not correct; our military power is. This is a dangerous mistake. Our alliances can be highly valuable, but to suggest that they are more important than our military capabilities is wrong and irresponsible.

The document says, “Our strategy is rooted in our national interests.” This assertion is at odds with the insistence that America will not act abroad except in concert with our allies and partners. The strategy claims that “Most nations around the world define their interests in ways that are compatible with ours.” That, however, is either banal or untrue. Our European allies have important differences with us regarding China, Iran, Israel, trade, and other issues. Before the Ukraine war, they had major differences with us regarding Russia.

The strategy says, “As we modernize our military and work to strengthen our democracy at home, we will call on our allies to do the same.” What if they do not heed the call? For decades, US officials complained vainly that NATO allies underinvested in defense, confident that the United States would cover any shortfalls—what economists call a free-riding problem. Along similar lines, the strategy declares that America’s alliances “must be deepened and modernized.” But how should US officials deal with allies who act adversely to US interests, as Turkey has so often done under Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan—in buying Russian air-defense systems, for example—and as the Germans did, before the Ukraine war, in increasing their dependence on Russian natural gas?

Interestingly, on strengthening the US military, the strategy does not say that US allies have to agree or cooperate. It says, “America will not hesitate to use force when necessary to defend our national interests.” This part of the document reads as if it had different authors from the rest.

Nuclear Deterrence

The strategy makes an important point about nuclear deterrence as “a top priority” and highlights that America faces an unprecedented challenge in now having to deter two major nuclear powers. It makes a commitment to “modernizing the nuclear Triad, nuclear command, control, and communications, and our nuclear weapons infrastructure, as well as strengthening our extended deterrence commitments to our Allies.” But the administration has not allocated resources to fulfill its words on deterrence and Triad modernization.

Promoting Democracy and Human Rights

“Autocrats are working overtime to undermine democracy and export a model of governance marked by repression at home and coercion abroad,” the strategy accurately notes, adding that, around the world, America will work to strengthen democracy and promote human rights. It would be helpful if it also explained why other countries’ respect for democracy tends to serve the US national interest. This is not obvious and many Americans, including members of Congress, show no understanding of how democracy promotion abroad can help the United States bolster security, freedom and prosperity at home.

The strategy does not explain how its championing of democracy and human-rights promotion can be squared with its emphasis on respecting the culture and sovereignty of other countries and not interfering in their internal affairs. Nor does it explain how officials should make trade-offs between support for the rights of foreigners and practical interests in dealing with non-democratic countries. Officials need guidance on such matters. The public also would benefit from explanations.

The administration just announced that Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, who is also prime minister, has immunity from civil liability for the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi journalist who worked for The Washington Post. The strategy does not shed light on how the relevant considerations were weighed. It says the United States will make use of partnerships with non-democratic countries that support our interests, “while we continue to press all partners to respect and advance democracy and human rights.” That’s fine as far as it goes, but it does not acknowledge, for example, that we sometimes have to subordinate human rights concerns for national security purposes, as when President Franklin Roosevelt allied with Josef Stalin against Adolf Hitler. A strategy document should be an aid in resolving complexities, not a simplistic list of all the noble things we desire or wish to be associated with.

Refugees

Regarding refugees, it is sensible that the strategy reaffirms the US interest in working with other countries “to achieve sustainable, long-term solutions to what is the most severe refugee crisis since World War Two—including through resettlement.” But there is no mention of why US officials should press Persian Gulf states to accept more refugees from the Middle East, given that those states share language, culture, and religion with those refugees.

Willing Ends Without Providing Means

The strategy does a lot of willing the end but not specifying or providing the means. As noted, the administration is not funding defense as it should to accomplish its stated goals. On Iran, the strategy says, “[W]e have worked to enhance deterrence,” but US officials have been trying to revive the nuclear deal that would give Iran huge financial resources in return for limited and unreliable promises.

The strategy says, “We will support the European aspirations of Georgia and Moldova . . . . We will assist partners in strengthening democratic institutions, the rule of law, and economic development in the Western Balkans. We will back diplomatic efforts to resolve conflict in the South Caucasus. We will continue to engage with Turkey to reinforce its strategic, political, economic, and institutional ties to the West. We will work with allies and partners to manage the refugee crisis created by Russia’s war in Ukraine. And we will work to forestall terrorist threats to Europe.” But these items are presented simply as a wish list, without explanation of the means we will use, the costs involved, or the way we will handle obvious pitfalls along the way.

Setting Priorities

A strategy paper should establish priorities, but this one simply says we have to do this and that, when the actions are inconsistent with each other. It is, line with the quip attributed to Yogi Berra, “When you get to a fork in the road, take it.” It says we should act in the US national interest, but we should also always act with allies and partners. We should oppose Chinese threats, but always cooperate with China on climate issues. We should pursue the nuclear deal with Iran even when Iran is threatening its neighbors and aiding Russia in Ukraine (and, as noted, crushing its domestic critics). We should insist on a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestinian conflict while the Palestinian Authority remains unreasonable, corrupt, inflexible and hostile.

A strategy should not set up choices that involve trade-offs and then give no guidance on how to resolve the trade-offs. If it promotes arms control and other types of cooperation (on COVID, for example) with Russia and China, it should forthrightly address problems of treaty violations and specify ways to obtain cooperation when it is denied.

Such a document cannot specifically identify all possible trade-offs and resolve them, but it can set priorities and do a better job than this strategy does in informing officials on how to handle easily anticipated dilemmas.

Strategic Guidance or Campaign Flyer

The administration’s strategy combines valid points and unreality. It is unclear whether it is a serious effort to provide guidance, directed at officials, or a boastful campaign document, directed at the public. Mixing the genres is not useful.

Douglas J. Feith is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute. He served as Under Secretary of Defense for Policy in 2001-2005.