When Barack Obama was awarded the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize, the committee expected he would make “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples.” More than three years later, Mr. Obama has failed to meet expectations, but it has not been for lack of trying. His administration has consistently promoted international harmony and downplayed the root causes of global strife. And in so doing he has given an opening to adversary states and extremist movements to pursue their interests at America’s expense.

When Barack Obama was awarded the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize, the committee expected he would make “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples.” More than three years later, Mr. Obama has failed to meet expectations, but it has not been for lack of trying. His administration has consistently promoted international harmony and downplayed the root causes of global strife. And in so doing he has given an opening to adversary states and extremist movements to pursue their interests at America’s expense.

One difficulty in assessing Mr. Obama’s policies towards U.S. competitors is that the administration carefully avoids acknowledging that adversary states exist. This outlook was typified in the 2010 National Security Strategy. With the exception of the al-Qaeda terrorist network, the strategy does not identify any countries as standing threats to U.S. interests. The challenges the White House will acknowledge—such as violent non-state extremist groups, nuclear proliferation, global warming, economic contraction, and the spread of pandemic disease—come across as free-floating phenomena unconnected to state actors.

The overarching theme of the Obama strategy is “engagement,” based on a foundation of “shared interests and shared values…which serve our mutual security and the broader security and prosperity of the world.” Any challenges that arise “hold out the prospect of opportunity,” provided countries can break down “the old habits of suspicion to build upon common interests.” Unfortunately this approach fails to recognize that more often than not, global tension is the product of competing interests and clashing values. The White House claims that “power, in an interconnected world, is no longer a zero sum game,” but most countries have yet to receive that memo.

Russian Reset

Russia has never approached the world from a positive-sum perspective. Moscow has long been viewed as a natural strategic competitor to the United States, but is not by the Obama administration. The Obama National Security Strategy notes dryly that in recent years “Russia has reemerged in the international arena as a strong voice,” without detailing the ways that Moscow has sought to use its growing power to frustrate American interests in Europe and the Middle East. Critics who are concerned about Russia’s increasing boldness under the leadership of President Vladimir Putin are shrugged off as being captive of a lingering Cold War mindset. Obama’s much-heralded “reset button” approach to the Kremlin was founded on the belief that Russo-American competition was the result of past misunderstandings and poor communication rather than conflicting strategic interests. Consequently, Washington put everything on the table—particularly key sources of Russian discontent such as European missile defense and strategic nuclear arms—in hopes of generating reciprocal good will from Moscow. This has not been forthcoming.

The Obama administration points to the 2010 New START nuclear arms reduction treaty with Russia as an example of the types of agreements that are possible when old animosities give way to cooperative effort. The treaty limits each country to 1,550 operational strategic nuclear warheads—a two-thirds reduction from the original START treaty. However, it did not limit the number of stockpiled warheads, and since Russia is in the midst of a significant nuclear weapons modernization program, the net effect of the treaty was to commit the United States to weapons cuts while allowing Russia to engage in an arms buildup. That, plus a weak verification regime, made New START an easy treaty for Moscow to sign. Despite its name, New START did not herald a breakthrough in bilateral understanding; it was simply a very bad deal.

Unilateral Nuclear Disarmament

The belief that there are no permanent American enemies has led the administration to question the need for a permanent deterrent. In 2009, Mr. Obama endorsed the Global Zero concept of a world without nuclear weapons. In June 2012, the Obama administration announced it would seek to reduce operational American nuclear warheads to 1,000—a third less than the ceiling under New START. The White House strategy seeks “reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security approach,” but is in fact practicing slow-motion unilateral nuclear disarmament.

The administration claims that U.S. nuclear strength will not be reduced below the amount needed for effective deterrence, yet it is unclear what that level may be. A glaring gap in administration strategic thinking is the People’s Republic of China, which is not a party to any nuclear arms limitations treaties and has never revealed how many warheads it possesses. Like Russia, China is modernizing its nuclear forces and pursuing aggressive maritime and space strategies that directly threaten U.S. interests. Furthermore the Obama administration has promised to extend the U.S. nuclear umbrella to states concerned about regional nuclear proliferation even as it seeks to reduce the size of the force. The net effect of this confused approach is to shift the strategic balance away from the United States and reduce the credibility of what deterrent forces remain.

Even rogue state nuclear proliferators are treated with kid gloves in the Obama worldview. The 2010 strategy pledges the U.S. to “pursue the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula and work to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon.” But it quickly cautioned that “this is not about singling out nations—it is about the responsibilities of all nations and the success of the nonproliferation regime.” However, without singling out and dealing with problem states there is no practical way to stop proliferation. The administration’s knee-jerk instinct not to offend even countries engaged in the worst sort of destabilizing behavior sends a signal of weakness that makes correcting the problem that much harder.

Olive Branch to Iran

The most proximate threat comes from the Islamic Republic of Iran. In his first week in office Mr. Obama adopted an olive branch posture, and announced to Tehran that the United States would “extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist.” At the time there was heady talk of a “grand bargain” with Iran and other regional powers that would resolve all the outstanding issues of the Mideast region. But this approach was highly unrealistic and quickly foundered. A popular uprising in Iran in the summer of 2009 took the administration by surprise, and while Mr. Obama dithered the revolt was brutally suppressed. Afterwards Tehran’s fist was clenched as tightly as ever.

In the years since, the Obama administration has repeatedly renewed its call for a thaw in the cold war with Iran, while simultaneously maintaining pressure on Tehran’s growing nuclear program. Yet the White House has failed to take adequate steps to dissuade Iran from its nuclear course. Possessing nuclear weapons is a vital national interest to the Islamic Republic, and its leaders are not convinced that Mr. Obama is seriously committed to stopping its program.

Iran’s model is North Korea, one of the poorest, most economically and diplomatically isolated countries in the world, which nevertheless became a nuclear power. Pyongyang faced the same threats from previous American administrations that Tehran does now. When the communist regime tested its first nuclear device in 2006, the George W. Bush administration blinked. Washington shifted from saying North Korea would not be permitted to have nuclear weapons to saying they would not be permitted to have any more such weapons. This precedent, and a general sense that Mr. Obama is even less willing to take the steps necessary to back up U.S. policy than Mr. Bush was, has created a large enough credibility gap for Iran to keep its nuclear program running.

The failure of the diplomatic, economic, and intelligence elements of national power to dissuade Iran points towards the need for a more vigorous and sharply defined use of military force. But the Obama administration has sent mixed signals. Simply repeating the mantra that “all options are on the table” is insufficient, especially when administration actions show that some options are not available. Ongoing public disputes with Israel over future courses of action have fed a sense of ambiguity and encouraged Iran to move ahead. Paradoxically, Mr. Obama’s unwillingness to say definitively when force will be used has made a sudden preemptive strike by Israel more likely.

Supporting Political Islam

The most significant gap in Mr. Obama’s strategic thinking concerns the challenge posed by the increasing political power of radical Islamists. The administration points with pride to the comprehensive counterterrorism strategy it has pursued against the al-Qaeda network, and the 2011 raid that killed Osama bin Laden. However this effort is limited to the threat posed by “violent extremism,” not extremism per se. In fact the White House does not even recognize that the rise of political Islam poses a significant challenge to American interests.

This conceptual blindness has been vividly on display in the wake of the Arab uprising. The State Department praised the 2012 electoral victories of the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafist political parties in Egypt. It noted that the increasing influence of such radical groups was helpful because “people who once might have gone into al-Qaeda see an opportunity for a legitimate Islamism.” The White House even maintained triumphantly that the Islamist electoral victory discredited al-Qaeda’s model of violent change. But this betrayed a serious intellectual confusion between means and ends. Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri soon put matters into perspective, noting that his group was happy to see the downfall of the old regime in Egypt by any means. Zawahiri affirmed that his group seeks the implementation of Sharia law and would be satisfied whether it arrived by the ballot or the bullet.

Mr. Obama seems unable to differentiate between Muslim religious faith and Islamist political ideology. His respect, or reverence, for the religion he grew up around has become a roadblock for a sober appreciation of the strategic challenge posed by political Islam. U.S. policymakers refuse to address the implications of the rise of governments that specifically reject the purportedly universal values on which Mr. Obama has sought to base his engagement strategy. The White House shows no signs of planning for a future in which this clash of civilizations will be the central strategic question in the region. In fact, they stubbornly deny it is even happening.

This state of denial was evident in the aftermath of the violence and demonstrations that swept the Muslim world starting on the 11th anniversary of the September 11 terrorist attacks. The administration blamed the protests on a YouTube video that insulted the Muslim faith. But it has avoided addressing the deeper issue of discontent over U.S. policies and declining regard for Mr. Obama in particular. In his September 25 speech before the United Nations, Mr. Obama repeated his standard pleas for understanding and cooperation. But the same well-worn platitudes will not bring peace and stability. The president has shown no inclination to take the hard stands necessary to prevent the Middle East from devolving into oppressive Islamist orthodoxy. Meanwhile anti-American sentiment continues to grow, and non-Muslim religious minorities face increasing persecution. Most importantly the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, which has been the lynchpin of regional stability for three decades, may soon be a thing of the past.

The Obama Doctrine Meets Reality

The Obama administration’s failure to stand up to America’s adversaries is rooted in a flawed belief that all countries share a common vision of global peace and harmony. It is based on an idealistic vision of a world in which events need not be dictated by the competition over interests. This has lent a generally passive and non-confrontational tone to U.S. messaging. And lurking behind this approach is a mistaken confidence in the power of Mr. Obama’s charisma to help usher in this new world. Unfortunately for this approach, world leaders have had no difficulty saying no to Mr. Obama when their interests demanded it.

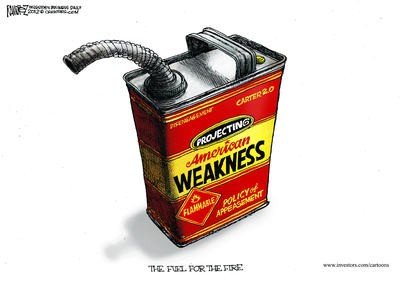

The results of the Obama doctrine are greater global instability and a general sense of drift in world affairs. U.S. interests are not advancing in any region in the world. America’s friends have lost confidence, and its adversaries have been emboldened. Mr. Obama apparently believed that if the United States stopped rigorously pursuing its national interests, other countries would follow suit. Instead he has created an expanding power vacuum, which other countries and non-state actors are rushing to fill. It is safe to say these forces do not have American best interests at heart. As former U.N. Ambassador John R. Bolton said, “American weakness [is] provocative, and we have a very provocative president in the White House.” Mr. Obama has decided that the United States has no enemies. If only America’s enemies agreed.

Dr. James S. Robbins is senior fellow in national security affairs at the American Foreign Policy Council, and senior editorial writer for foreign affairs at The Washington Times.