The Unlikely Imperialists

The transformation over the past decade of the intellectual framework in which U.S. power and influence are understood by some of our leading thinkers has been nothing short of astonishing. Shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall, for example, Yale’s Professor Paul Kennedy was warning against American “imperial overstretch” in his bestseller, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (Vintage, 1989). More recently, and especially in the aftermath of 9-11, Kennedy has been pushing for a Pax Americana. “Nothing has ever existed like this disparity of power,” Kennedy wrote in London’s Financial Times. “The Pax Britannica was run on the cheap . . . right now all the other navies in the world combined could not dent American maritime supremacy.” Indeed, for Kennedy, no empire has ever even been in the same league: “Napoleon’s France and Philip ii’s Spain had powerful foes and were part of a multipolar system. Charlemagne’s empire was merely Western European in its stretch. The Roman Empire stretched further afield, but there was another great empire in Persia and a larger one in China. There is no comparison.”

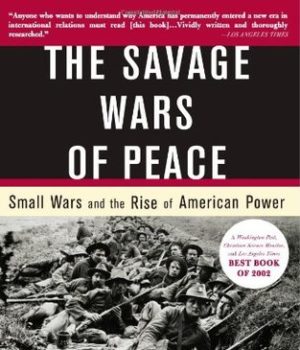

Kennedy is really more the norm than the exception. Increasingly, on both sides of the political spectrum, imperialism has been acquiring a new intellectual legitimacy. Enter Max Boot and his exhortation to imperialism: The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. It is an entertaining, provocative, and often insightful history of America’s “small wars” or low-intensity conflicts — i.e., military operations and engagements other than war. Boot takes his title from Kipling’s famous, indeed notorious, February 1899 imperial exhortation to the United States, “The White Man’s Burden,”

The savage wars of peace —

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) is probably the most significant literary advocate of imperialism in the English language. He was far and away the biggest icon of the British Empire, promoting the imperial prerogative of bettering the “lesser breeds without the Law.” And although Kipling was less a racist than is generally thought, Boot’s casting himself in with the poet is no less courageous in this era of political correctness.

Boot, the editorial features editor of the Wall Street Journal, has sounded this imperial note before and loudly. So it is no surprise that he has crafted a thumping good, rock’em-sock’em sort of narrative. Heroics, adventure, graphic battles, gory details, etc. — it is almost enough to rouse even a dyed-in-the-wool pacifist to chase imperial glory in jodhpurs and a pith helmet. The book is both scholarly and effective, and it would certainly have met with Kipling’s approval.

When I first picked up Max Boot’s book, however, the first Kipling poem that came to mind, oddly enough, was not “The White Man’s Burden,” but his lesser known “Danegeld,”

To puff and look important and to say: —

“Though we know we should defeat you, we have not the time to meet you,

We will therefore pay you cash to go away.”

And that is called paying the Dane-geld;

But we’ve proved it again and again,

That if once you have paid him the Dane-geld

You never get rid of the Dane.

Which nicely captures the way the West has treated Islamist thug states, particularly during the United Nations World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa — just one week before the hijacked airliners slammed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Kipling’s little ditty also pretty well enuppercaseulates the dangers of not properly taking care of a festering problem. If the Treasury were to be tapped, it would be better to chastise the thugs through a show of force than to pay them off. Force is older and generally more eloquent than cash, and self-preservation usually trumps economic gain. Indeed, sometimes there is nothing like a small war to set things right.

And as Max Boot’s book makes clear, our most recent small war in Afghanistan is closer to our historical norm than the Civil War, Korea, or either of the world wars. The U.S. has patrolled and fought undeclared wars and engaged in military interventions in the Marquesas Islands, Samoa, Korea, China, the Philippines, Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Russia, Grenada, Somalia, the former Yugoslavia, and across North Africa. (In 1882 in Alexandria, Egypt, “American sailors and marines . . . [became] the first foreign troops to enter the city center.”) Indeed, “between 1800 and 1934,” Boot informs us, “us Marines staged 180 landings abroad. The army and navy added a few small-scale engagements of their own. Some of these excursions resulted in heavy casualties; others involved almost no fighting. Some were concluded in a day or two; others dragged on for decades. Some were successful, others not.” What ties them all together, however, is their largely imperial nature, and through them Boot tries to chronicle the political course of American Empire.

He presents a basic taxonomy of these small imperial wars: punitive (to punish the bad guys), protective (to protect U.S. citizens and interests in a foreign land), pacification (the occupation of foreign territory to bring peace and order to rebellious and unlawful masses), and profiteering (the demand for trade or territorial concessions). “The primary characteristic of small wars,” says Boot, “is that there is no obvious field of battle; there are only areas to be controlled, civilians to be protected, hidden foes to be subdued.” For Boot, the term “small wars” refers strictly to tactics, not the scale of conflict. So the Spanish-American War is out — but Vietnam is in, and how.

Probably his two most interesting and crucial chapters are on Vietnam: its history and its legacy. In telling Vietnam’s history, Boot asserts that by the time the U.S. was embroiled in the conflict, the military establishment had forgotten all about the incisive Small Wars Manual the Marine Corps had developed during the 1930s (the Marines having long embraced these imperial missions as part of their reason for being). A rather hefty claim, though Boot makes it a plausible one. He then “reinterprets the Vietnam War through the prism of small wars,” persuasively arguing that Gen. William Westmoreland’s decision to fight a conventional war played directly into North Vietnamese Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap’s hands and ensured a U.S. defeat.

Boot also tells the history of the U.S.’s “other war” in Vietnam — “the pacification struggle,” also known as “nation building.” Most important of these efforts was the Combined Action Program, a Marine initiative modeled after the constabularies they had previously set up in Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua. In concert with South Vietnam’s Popular Forces militia, the cap created villages and hamlets that helped consolidate support for the American forces and for the South Vietnamese government. These pacified villages also helped to stave off Vietcong infiltration. Boot rather convincingly argues that this pacification program was a tremendous success.

When it comes to Vietnam’s legacy, however, Boot really takes the gloves off, especially laying into Gen. Colin Powell’s eponymous doctrine articulated during his tenure as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the first Bush administration: “that America should unsheathe its sword only when its vital interests are threatened, and then only if it is prepared to use overwhelming force with total public support to achieve a fast victory and then go home.” Boot elucidates how ill-suited this doctrine is for the real world and especially for the post-Vietnam conflicts that America has been involved in: Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, and Kosovo. Boot also quickly disproves the “body bag syndrome,” according to which support for a military excursion wanes with the first U.S. casualties, as well as the idea that most soldiers are averse to fighting small wars.

All of which leads to Boot’s final chapter, “In Defense of the Pax Americana.” Here, Boot reiterates a few of the lessons he takes from American history: There is absolutely nothing novel about “wars without a declaration of war,” “wars without exit strategies,” “wars that are fought less than ‘wholeheartedly,'” “wars in which us soldiers act as ‘social workers,'” “wars in which America gets involved in other countries’ internal affairs,” “wars without a ‘vital national interest,'” “wars without significant popular support,” or “wars in which us troops serve under foreign command.” Boot establishes all of these lessons very firmly. What is missing, however, is a larger normative argument. Fine, yes, these sorts of conflicts pepper our nation’s history, but so what? Why does that mean we should embrace them now?

Boot does not quite get around to arguing for a coherent ideology or a historical narrative gloss linking these small wars. He does not posit a liberty doctrine or a variant of manifest destiny or some such vision that might reasonably demonstrate the quest for empire. He merely highlights a continuity of small war engagements — each of them has an imperial tinge, but together they do not make up a broad, overarching imperialism.

He makes several attempts to ground Pax Americana, but, frankly, they are not so compelling. “A world of liberal democracies would be a world much more amenable to American interests than any conceivable alternative”; “without a benevolent hegemon to guarantee order, the international scene can degenerate quickly into chaos and worse”; “why not use some of the awesome power of the us government to help the downtrodden of the world, just as it is used to help the needy at home?” Yes, again, these all sound well and good. But is the world truly yearning for an imperial lawgiver? Does America truly wish to unilaterally be that lawgiver? Would America wish to be part of a multilateral effort to better the world?

Since around 1945, the U.S. has played the imperial role very indirectly: exercising economic leverage through multinational corporations and international agencies like the International Monetary Fund and political power through “friendly” indigenous regimes. But as Britain discovered in the nineteenth century, there are limits to what can be achieved through informal imperialism. Puppet rulers can be overthrown by revolution, or simply through a tribal power grab. As a practical matter, foreign aid has often served mainly as an enabler for corruption among ruling elites when it has not been misdirected into prestige projects inimical to sound development or used as a backdoor way to subsidize arms sales or engineering projects. Also, new regimes can default on their debts, disrupt trade, and go to war with their neighbors — even sponsor terrorism.

Indeed, this sort of indirect imperialism may illuminate the fundamental problems of the Arab states. Unlike Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas, the Arabs have never come under direct European colonial rule. Instead, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Arabian Peninsula was carved up into “spheres of influence.” So, rather than occupy the country, establish the rule of law, introduce a mandarin class, and set up other features of a civil society, the British, French, and, later, the Americans simply looked for some pliable sheik and installed him in the palace. Indeed, this is very much the problem that the Western world, particularly the U.S., still faces.

During the Clinton years, the United States, slowly and rather unreflectively, responded to crises of this sort by intervening directly in the internal affairs of faraway countries. True, it tried to do so with a veneer of multilateralism, acting in the name of the United Nations or nato. But the precedents set in Bosnia and Kosovo were significant. Such territories became a new kind of colony: international protectorates underwritten by U.S. military and monetary might. Essentially, it is the imperialism that evolved in the 1920s when League of Nations mandates were the polite word for what were the post-Versailles treaty colonies. Does any of this quite reach the level of empire? Perhaps — but only indirectly.

This indirect international influence is not the same as global hegemony. Nor does a Pax Americana seem likely, given the higgledy-piggledy nature of American “imperial” efforts. In this respect, Boot’s take-your-pick approach to persuasion bespeaks the fact that Americans are unlikely imperialists. After all, despite our rich history of small war engagements, Americans remain mostly unaware that these conflicts ever happened; even our armed services, according to Boot, have only very recently become aware of this tradition and are still not yet of the right frame of mind about it. Indeed, this is largely why Boot decided to write this delightfully absorbing history to begin with.

As our nation was born in a war for independence from imperial rule, it should not be so surprising that Americans have not been eager to rule others in that way. Further, Americans — if electoral and civic participation is anything to go by — are generally not so interested in politics and government-directed social-engineering projects. If we don’t care for it at home, why should we wish to ship it abroad? (Though it is most assuredly better out than in.) Besides, our nation is currently a net importer of capital and talent, and we are still considered prime relocation potential for immigrants and asylum seekers around the globe. The U.S. is simply not the premier producer of would-be colonial emigrants.

Seen from a more global and long-term historical perspective, however, the ultimate problem for Pax Americana is simply that Americans do not have the stomach to pursue a proper imperialism. Nor have we any longer a national sense of honor that might compel us to conquer others.

In very rough terms, empire-building has always been first and foremost about national gain — fortune, power, and security. Of secondary, though not insignificant, importance is the moral self-justification: acting as a stabilizing and, more important, a controlling force for good in the world. In this respect, the best case for direct and formal Pax Americana is hinted at in Boot’s title. It is Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden,” the moral imperative to better the lot of the benighted, bemused, and besotted of the world. It is rooted in what are now considered archaic, if not evil, notions of the moral superiority of one’s way of life and the rightness of forcing it upon others for their own sake. Either you believe that might makes right and God is backing you to the hilt, or you don’t. That is the point of global hegemony and has been from time immemorial. It is, to be sure, a religious and missionary frame of mind and one that is almost entirely foreign to the American experience.

Though Pax Americana seems entirely unlikely, America does find itself, more or less by default, as the lone superpower. And thus Boot is on much stronger ground when he elaborates his basic theme: Small wars, a regular feature of our past, are an inevitable feature of our present and future. We should embrace them and fight them well. Such conflicts are an unavoidable outgrowth of the global reach of America’s power and interests, as they have been since our independence. America can’t be the big boy on the Western block and also avoid small wars.

If, further, we are to fight these small wars, it is necessary to be “bloody-minded” about it — we need to stop being squeamish about exercising our power and flexing our muscles. The specter of Vietnam is just a lot of nonsense wedded to very specific, historical, tractable, and avoidable mistakes. While this might seem like meager justification for the pursuit of empire, it all happens to be quite true. Further, Boot’s book helps establish that historical continuity implies a certain commonality. More important, his argument does not in any way entail some idealized virtue about the power and efficacy of man’s ability to reshape the world around him to his liking, nor does it rely upon some vision of the world as it ought to be.

Which brings Kipling back to mind:

They denied that the Moon was Stilton; they denied she was even Dutch.

They denied that Wishes were Horses; they denied that a Pig had Wings.

So we worshipped the Gods of the Market Who promised these beautiful things.

They swore, if we gave them our weapons, that the wars of the tribes would cease.

But when we disarmed They sold us and delivered us bound to our foe,

And the Gods of the Copybook Headings said: “Stick to the Devil you know.”

Fortunately for us, Boot elucidates very nicely the devil our country knows best and helps establish what should have been obvious to students of our nation’s history: Small wars are not going away.

Josh London is the policy director of the Jewish Policy Center, a think tank based in Washington, D.C.