The Lebanese parliament passed a bill yesterday granting the country’s 400,000 Palestinian refugees the right to work in the same professions as other foreigners, lifting a ban dating back to 1946 that relegated the refugees to below foreigner status and the most menial of jobs. Indeed, unlike in Jordan, where Palestinians enjoy more rights – albeit not by much, Lebanon’s refugees live mostly on UN handouts and payments from Palestinian factions. Those who do work are generally either employed by the UN or are laborers in jobs such as construction.

While many, including Fatah, welcomed the new bill, it is hardly a step in the right direction. Refugees remain barred from working as engineers, lawyers and doctors, as those occupations are regulated by professional syndicates limited to Lebanese citizens. Moreover, Palestinian refugees are still not allowed to attend public schools, own property, or pass on inheritances.

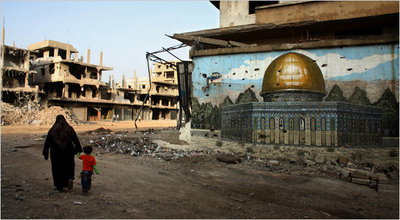

The Nahr al-Bared camp near Tripoli is seen here with damages from fighting between the Lebanese Army and Islamic extremists in 2007. |

|

Palestinians in Lebanon are largely discriminated against for two major reasons. First, unlike other countries in the region, Beirut’s government was established on a tenuous system of power sharing among Christians, Sunni Muslims, Shiite Muslims, and Druze. Since most of the refugees are Sunni, the remaining Lebanese sects fear that providing the Palestinians with citizenship would give more power to Lebanon’s Sunnis.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, just as in Syria, Beirut’s failure to resettle the Palestinian refugees is a political issue. Lebanon has exploited the Palestinian refugee problem by adopting binding restrictions on Palestinians’ rights in order to aggravate tensions in the region and undermine Israel. Indeed, by refusing to resettle the refugees, Lebanon has perpetuated the misery of some 400,000 Palestinians, keeping the refugees’ desire to return to Israel and parts of Mandate Palestine as a key and red line issue in peace negotiations. As such, for political purposes, Fatah would like Palestinian refugees to be granted more rights in the countries they reside in, without being offered citizenship. As Fatah party spokesman Ahmad Assaf put it, the refugee issue will be concluded once Palestinians are afforded the right of return.

Lebanon’s move to further incorporate Palestinians into the Lebanese work force should be taken with a grain of salt as the new bill is hardly a panacea for Lebanon’s Palestinian refugees. After all, now more than 60 years after Israel’s war for independence, Palestinians are finally having their status upgraded to that of a foreigner. In the Middle East, however, progress is often measured by inches rather than miles.