Two Books and an Agenda

The Western temptation to view the Middle East and North Africa as part of the “Muslim World,” of which the “Arab World” is a subset, makes politics simpler but does a disservice to what has historically been a multi-cultural, religious, and ethnic region. It also provides cover for the systematic assault on minority communities by the dominant Arab and Muslim cultures. If the West doesn’t know minorities are there, it won’t notice when they disappear. And they are disappearing.

The Western temptation to view the Middle East and North Africa as part of the “Muslim World,” of which the “Arab World” is a subset, makes politics simpler but does a disservice to what has historically been a multi-cultural, religious, and ethnic region. It also provides cover for the systematic assault on minority communities by the dominant Arab and Muslim cultures. If the West doesn’t know minorities are there, it won’t notice when they disappear. And they are disappearing.

Iraq, for example, is both Arab and Muslim—but there are non-Arab Kurds, Assyrians and Turkmen, and smaller groups of Azeris, Georgians, Armenians, Roma, Chechens, Circassians, Mhallami, and Persians. There are non-Muslim Christians, Mandeans, Yazidis, Yarsan, Shabak, Zoroastrians, and Bahais. The Jewish community dated from before the Common Era. But in 2011, Wikileaks published the names of what were reported to be the last seven, in hiding while they planned to leave. Iran is considered Persian, but nearly 40% of the Iranian population consists of Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Lurs, Baloch and Turkmen, Kazakhs and Qashqai. The percentage of ethnic Persians is actually rising slightly as others leave.

The percentage of non-Muslim people is declining precipitously—as many as half of Iraq’s 1.5 million Christians have left the country since the 2003 overthrow of Saddam. The Persian Jewish community, dating from the time of the Bible, continues to shrink from 100-150,000 in 1948 to 80,000 in 1979, to 8,756 today according to a 2012 census.

The lack of official and unofficial tolerance for “the other” is part of the reason the “Arab Spring” soured so quickly. Western ignorance or complacency remains a contributing factor.

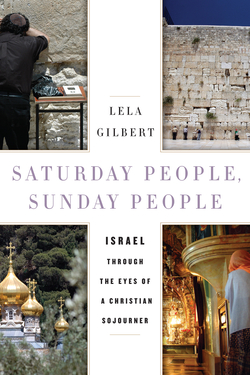

Lela Gilbert, an adjunct fellow at the Hudson Institute and a free-lance writer, brings the systematic decimation of Christian communities in the Middle East to the attention of the West in her new book, Saturday People, Sunday People: Israel Through the Eyes of a Christian Sojourner. It is actually two books and an agenda.

The first book is about Gilbert’s much-longer-than-planned visit to Jerusalem and her exploration of Israel. The second is about the decimation of Arab Christian communities, the follow-on to the expulsion of Jewish communities in the 20th Century. This explains her choice of the title, borrowed from radical Muslims who have long used the phrase, “First the Saturday people; then the Sunday people.” Gilbert examines both tragedies with great respect. The agenda is to use the Jewish history in Arab lands as a cautionary tale to sound the alarm about the increasingly monolithic Muslim Middle East, and to create a Christian-Jewish alliance to face Muslim violence against minorities.

The First Book

Gilbert came to Israel during the 2006 Lebanon war and learned that much of what she thought she knew about Israel wasn’t so. She stayed longer than planned, visiting Christian and Jewish holy sites in Jerusalem and in the North, visiting Sderot under Hamas rocket fire, Bethlehem and a “settlement.” She met and interviewed Israelis of all stripes. Her blunt and outspoken belief in the political rightness and essential humanity of Israel is refreshing and her wide-eyed astonishment with the media’s unfairness is almost shocking. A cynic might say it is rose-colored glasses—after all, Jerusalem does that to people—but it will come as a relief to those who have been talking about media and political bias for years. It is refreshing to have someone look at Israel with new eyes and see what many others have seen and write about it with such elegance. She captures sights, smells, and insights about the Jewish calendar, Jewish holidays, and her Jewish and Arab neighbors with appreciation and respect.

Aware of the persecution of European Jews, Gilbert discovers the Jewish refugees from Arab countries by accident: “So why hadn’t I heard about this ‘forgotten exodus’ before? I’d been in Israel for a few years by then. I’d read half a dozen lengthy histories of Israel or histories of the Jewish people, yet they had barely mentioned such a monstrous event. Why had nearly a million refugees fallen off the radar screen?”

She turns her attention to them and their progeny in a series of vignettes about Sephardic Jews, contrasting the relative obscurity of their stories with the exposure of Palestinian refugees and their descendants. “Hardly a day passes when the subject of the millions of Palestinians refugees seeking a ‘right of return’ to their lost properties—or compensation for them—isn’t discussed in relation to Middle East peace negotiations… the story of their losses and their controversial politicization is a familiar subject… Meanwhile, a different refugee story… is far less familiar.”

One Iraqi-born Israeli explains why: “I’ll tell you something about Iraqi Jews—in fact probably about Jews in general. We never look back. We always look forward. I’m not going to go back and claim a house, which used to be mine 40 or 50 years ago. I really couldn’t care less. I live for the future. The European Jews were the same way after the Holocaust. If you look back, you never go forward.”

The stories of Muslim persecution of Jews in Morocco, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and Syria segue seamlessly into tales of Muslim persecution of Christians in the same places.

The Second Book

The stories in the second book are ugly. Described in detail is the almost unreported 2010 massacre in the Assyrian Catholic Church of Our Lady of Salvation in Baghdad, in which 57 people including two priests and many children were killed during Mass. There is the 2012 incident in Mosul in which, “motorcycle-riding killers struck a Catholic priest’s family, breaking into the residence through a back entrance. They murdered Fr. Mazin Eshoo’s father and his two brothers, and raped his mother and his sister.” She describes the 2011 rampage in Cairo’s Maspero District in which at least 27 Copts were killed, and the harassment of converts in Morocco. The quiet decimation of the Bethlehem Christian community through intimidation by the PA government, Hamas, and assorted Muslim gangs gets a chapter of its own.

As she did with Jewish refugees, Gilbert provides historical background and then lets individual stories speak for themselves, either through persecuted individuals or through surviving family members. It was not necessary to juxtapose their tribulations against the horrific massacre of the Fogel parents and three of their six children 2011 in Itamar, but that is the segue to the third, and most uncomfortable, part of the book.

The Agenda

The last chapter, “Natural Allies in a Dangerous World,” postulates that Jews and Christians, as minorities, have to stand together to defend Israel and defend the remaining Christian communities of the Middle East. It is hard to argue against the proposition.

Gilbert has a sharp tongue for Muslim radicals and the politics of the Catholic Church. But she slides a little too lightly over the history of Christian-Jewish relations.

“Muslim hatred of Jews,” she writes, “is linked to hatred of Christians.” Radical Islamists, “demonstrate that, in their view, human life is of less value than the Islamic religion itself. Human beings—and their God-given breath of life—are found wanting in comparison to the sanctity of Islam’s holy book, the Quran. And the revered reputation of its prophet Mohammed. And calls to jihad—holy war—from radical leaders against non-Muslims.”

She calls out the Catholic Church’s political bias against Israel: “The Vatican’s Special Assembly for the Middle East of the Synod of Bishops… chose to focus on the ‘Israeli occupation’ of Palestinian territories rather than naming the actual perpetrators of ongoing violence against Christians; radical Islamic terrorists,” adding, “The Vatican’s focus on Israel, rather than on radical Islam, as the root cause of abuses against Christians, is both disingenuous and destructive.”

But she engages in a bit of disingenuousness herself when she discovers that Bethlehem’s Christians have anti-Jewish attitudes no different from those of radical Muslims, and place blame on Israel no differently than does the Catholic Church. She lets them duck: “As the leaders of the Arab Christian churches place the blame for the dangers facing Arab Christians squarely on the shoulders of Israel, they never hint that the radical religious jihadis or ‘Islamic Mafia’…are extorting, threatening, falsely accusing and sometimes murdering Christian Arabs.”

Gilbert appears not to consider that the Catholic Church may blame Israel precisely because it fears that Islamic violence against local Christians might be exacerbated by taking Israel’s side. Nor does she consider that Arab Christians may really share Arab Muslim anti-Jewish attitudes. It can’t go all one way for the Catholic Church and all the other way for the Arab Christians.

Selective Lessons from History

Of Christian persecution of Jews she writes, “It has been true that Jews and Christians have hotly disputed religious disparities… A number of our differences cannot and should not be compromised for the sake of mutual understanding, and we will continue to agree to disagree.” What she posits as mutual antagonism historically led to Jewish—not Christian—persecution. The Spanish Inquisition, for example.

“[I]t cannot be overlooked that the bloodshed suffered by Jews at the hands of so-called Christians over many centuries is a matter of historical record.” So, even where Gilbert acknowledges who was on which end of the persecution, she won’t call the bad guys Christians; they are only “so-called.” That dodge—her apparent belief that “real” Christians wouldn’t kill Jews for theological reasons, but “real” Muslims would—is actually the reason that “bitter mistrust continues to this day.”

It would have been better to say outright that the Christian ecclesiastical hierarchy and many practitioners treated Jews and Muslims precisely the way the Muslim ecclesiastical hierarchy and many practitioners treat Jews and Christians today—as people minimally in need of conversion and maximally doomed to die.

If that sounds churlish, it is only because Gilbert doesn’t then acknowledge the great efforts by various strong Church leaders over time who worked prodigiously to come to terms with and overcome the history of Christian persecution of Jews. Christians did not always appreciate them, but it is on the foundation of their work that Gilbert’s appreciation of Israel and the Jewish people stands.

A Natural Alliance

Saturday People, Sunday People is elegantly written, historically important, and politically relevant. Gilbert is correct that there is an immediate and deadly problem for Christian communities of the Middle East and that most of the world is ignorant of or unmoved by their plight.

Jews should be calling for the protection of minorities in the Middle East. Not because Jews were victims first, but because it is morally right, and because the growing intolerance of modern Muslims majorities will make it harder, if not impossible, for Arab and Muslim countries to find political openness and consensual government in the 21st century. The natural alliance is among people, individuals or groups of any religion or no religion, who understand that exclusionary and reactionary governments bode ill for their majorities and minorities alike.

Shoshana Bryen is Senior Director of the Jewish Policy Center.