In just a few months, the United States Africa Command—USAFRICOM, or simply AFRICOM—will celebrate its fifth birthday. Officially formed on October 1, 2008, AFRICOM has come to play an increasingly important role in the defense of U.S. and allied interests on the continent of Africa and beyond. AFRICOM has achieved this not simply through conducting military operations, such as the case of Libya in 2011, but also through Theater Security Cooperation (TSC) across the entire continent of Africa. In fact, AFRICOM’s security cooperation efforts are arguably the Command’s most important contribution to U.S. national security, forming a critical enabling element in American defense, diplomatic, and development efforts across Africa. Through TSC events, activities, and programs, AFRICOM enables Africans to solve African security challenges, ultimately saving American lives and treasure in the pursuit of both vital and important U.S. interests across the continent.

The Newest Combatant Command

AFRICOM is the newest of what the Department of Defense calls its Unified Combatant Commands. These commands are both geographic—such as the European Command (EUCOM), the Pacific Command (EUCOM), and AFRICOM—as well as functional—such as Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) or Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM). They provide unified command and control of all assigned U.S. military forces, regardless of service, in their geographic or functional area of responsibility.

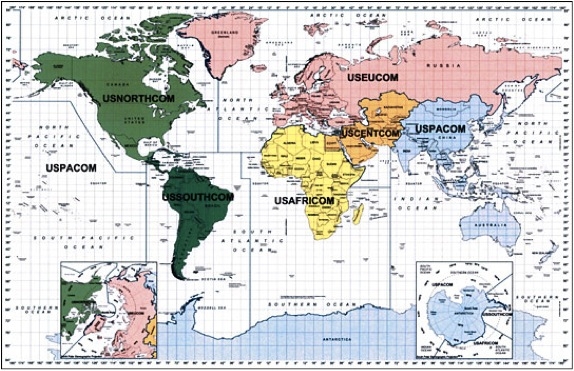

Hence, the Commander of AFRICOM—currently U.S. Army General David Rodriguez—has command and control responsibility for all assigned U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps forces in his specific area of responsibility, as depicted in Figure 1. Today, there are six geographic and three functional combatant commands.

Figure 1: Unified Command Plan. Source: U.S. Department of Defense. |

Why an Africa Command?

Prior to the establishment of AFRICOM, three separate combatant commands—EUCOM, CENTCOM, and PACOM—divided responsibility for assigned U.S. military forces, operations, and activities in Africa, resulting in a fractured approach to defense and security issues across the continent as well as an occasional lack of focus by military commands with attention devoted elsewhere in their areas of responsibility. AFRICOM’s formation enabled the United States to better address growing challenges to American and allied interests in a more focused way across Africa, particularly in the context of two phenomena. First, since at least the mid-1990s, the U.S. Government has recognized that some of the most significant risks to the security of the United States and its allies come not from conquering states but from failed or failing ones. Such states threaten their neighbors by becoming regional security headaches, exporting political conflict, economic instability, and/or religious and ethnic strife. When local conflicts become regional ones, there is a greater likelihood that U.S. interests, or those of American allies, will ultimately be affected. The case of Libya’s descent into civil war provides a recent example of this. Attacks by the Qaddafi regime against the Libyan people threatened to produce a wave of refugees that would have flooded across the Mediterranean Sea into Italy. Said Italian Foreign Minister Franco Frattini in February 2011, “…we are extremely concerned about the repercussions on the migratory situation in the southern Mediterranean.” European Union (EU) officials in Brussels estimated that up to 750,000 refugees might have attempted to make their way across the Mediterranean, adding to a major immigration challenge already existing in southern Europe, which is an important gateway for legal and illegal migrants from North and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Perhaps more importantly, failed or failing states also can ultimately threaten U.S. interests more directly and immediately by becoming incapable of fully or effectively governing their own territory. When this happens, criminals, traffickers, and terrorist organizations can fill the vacuum created by the lack of capable governance. The most obvious example of this was Afghanistan in the 1990s—years of civil war created conditions that enabled Al Qaeda to develop a safe haven, which ultimately contributed to the 9/11 attacks in the United States. Elsewhere, Somalia, Mali, and Yemen all provide recent examples of places where governance vacuums—or what some have called “alternative governance” structures—resulted in safe havens that terrorist organizations took advantage of, in some cases directly threatening the security of U.S. citizens and interests. Reducing or eliminating these safe havens reduces the likelihood of a major terrorist attack against the United States.

The second phenomenon driving the formulation of AFRICOM has been increased U.S. economic interests in Africa. Trade between the United States and the countries of Africa have risen steadily over the last several years, from just over $30 million in 1997, to over $140 million in 2008.

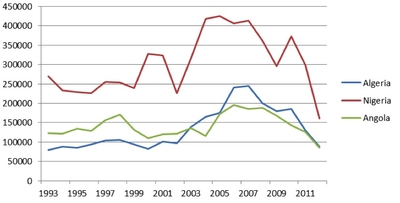

Figure 2: U.S. Petroleum Imports, 1993-2012, in thousands of barrels. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration. |

However, the most important element in the trade relationship is energy. Since the oil crises of the 1970s, the United States has sought to diversify its energy suppliers beyond the Middle East, resulting in an increasing emphasis on petroleum producers in Africa, among other regions. As Figure 2 shows, U.S. petroleum imports from Algeria, Angola, and Nigeria—Africa’s three largest petroleum producers—grew from the early 1990s until the Great Recession of the late 2000s.

Thanks to the unconventional fossil fuel revolution unfolding across North America today, the importance of Africa as an energy provider for the United States may diminish over the next few years—for instance, some reports already suggest that American imports of African crude oil this year will fall 12 percent from 2011 levels. This may reduce the salience of economic factors in the relationship between the United States and Africa. However, given the expected challenges in achieving effective sovereign governance across the continent, the potential for terrorist or other illicit activity inimical to American interests will likely remain a critical concern for AFRICOM and the U.S. Government.

Form Follows Function

Just as the security environment led to the establishment of AFRICOM, so too did it decisively shape the relatively new command’s structure and design. Cognizant of the need to work as collaboratively as possible with the State Department, given the nature of the many governance-related security challenges in Africa, the Defense Department created coequal deputy commanders within AFRICOM—one for civil-military affairs, and the other for military operations. The former—a senior State Department official usually of ambassadorial rank—presides over AFRICOM’s health-related missions, humanitarian assistance and de-mining action programs, disaster response, security sector reform, and Peace Support Operations.

Even though it has shifted toward becoming more of a traditional geographic combatant command in recent years, AFRICOM retains several unique features, such as a significant civilian staffing component that includes representatives from ten U.S. Government departments and agencies. AFRICOM’s structure is also unique in that it has no formally assigned U.S. military forces——the 2,000 or so troops assigned to the Horn of Africa task force in Djibouti are not permanently assigned to AFRICOM, despite the ongoing mission there. Hence, AFRICOM must request forces through the Defense Department’s “Request For Forces” (RFF) process, competing against myriad other Department-wide requirements and requests. With all of the military services downsizing, the defense budget under increasing pressure thanks to sequestration, and efforts to rebalance to the Pacific, it may become increasingly difficult for AFRICOM to compete for forces—even as fewer U.S. military units are deployed to Afghanistan. However, the U.S. Army’s recently unveiled initiative to regionally align military units with combatant commands may ameliorate some of this challenge, making it easier for AFRICOM to get the personnel and units necessary to fulfill its growing array of tasks.

The Security Cooperation Mission

Although AFRICOM has most recently been the focus of popular attention for its role in Libya and its support of French operations in Mali, the Command’s most significant—and arguably most important—operations and activities attract far less attention. Working closely with the State Department—and often operating with State Department funding and authority—AFRICOM engages in TSC activities to enable African countries to create a security environment that promotes stability, improved governance, and continued development. AFRICOM does this by working with security forces across the continent, all in coordination with the relevant U.S. embassy.

During his 2013 State of the Union address, President Obama spoke of the importance of enabling the security capabilities of partner and allied countries. “We don’t need to send tens of thousands of our sons and daughters abroad, or occupy other nations,” said the President, “instead, we will need to help countries like Yemen, Libya, and Somalia provide for their own security, and help allies who take the fight to terrorists, as we have in Mali.” Helping these countries to help themselves promotes U.S. interests in stability and security.

AFRICOM achieves this through TSC events and activities that are developed and calibrated for the specific challenges faced by different countries and regions across Africa. For example, in Somalia, AFRICOM has played a critical role in conducting pre-deployment training for African Union (AU) forces from Burundi, Djibouti, Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Uganda under the auspices of the State Department’s Global Peace Operations Initiative. There is increasing evidence that AFRICOM’s training effort is having a tangible benefit in helping AU forces to degrade the capabilities of al-Shabab, an al-Qaeda affiliate operating in Somalia.

Elsewhere, in South Sudan, Africa’s newest country, AFRICOM supports the ongoing State Department security assistance program through its efforts to build basic military capacity by educating key military institutional-level personnel and through small-scale civil action projects with the South Sudanese military. And in more stable African countries such as Botswana, AFRICOM builds partner country capability to participate in or lead peacekeeping operations, or assists partner countries in integrating women into their military services.

These and similar efforts across the continent—when crafted and tailored to the specific needs and requirements of individual African partner countries—enable African forces to solve African challenges, which is far cheaper and arguably more effective than handing those same missions to U.S. forces. While African militaries contribute to building security and stability across Africa, they also directly and indirectly support American and western interests, which may not be vital or clear cut enough to justify the introduction of U.S. or NATO troops on the ground but which nonetheless demand some level of attention from Washington and those that share its perspective. Assuming it can mitigate challenges posed by defense budget cuts, decreased U.S. military manpower, and a national security bureaucracy increasingly focused on the Pacific, AFRICOM will likely continue to play a critical, cost-effective role in safeguarding U.S. interests in Africa through security cooperation.

Dr. John R. Deni is a Research Professor of Joint, Interagency, Intergovernmental, and Multinational Security Studies at the U.S. Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute. You can follow him on Twitter at @JohnRDeni. The views expressed are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.