An analysis of the defense budget does not fully capture the state of the U.S. military. But the numbers do tell us that the U.S. Department of Defense is the world’s largest organization. Its annual budget was $578 billion last year. It employs just under three million people. It owns or operates 557,000 facilities in the U.S. and around the world with real estate valued at more than $800 billion. To organize, train, and equip the U.S. military, this federal agency also has its own school systems, health care management system, and grocery chains. It runs its own versions of FedEx and Amazon. And it develops and purchases some of the most complex technology ever contemplated. Examining the Defense Department as a whole can be daunting.

Too often, the emphasis is on how much its efforts cost rather than what they buy the American people. To begin to determine the state of the U.S. military, policymakers should examine four areas: (1) readiness, (2) capacity, (3) capability, and (4) the health of the all-volunteer force. Readiness describes whether the armed forces are fully trained to carry out the missions they might need to perform. Since the U.S. military relies heavily on superior training in combat, the current readiness shortfall worries commanders. On a broader level, the readiness of the U.S. military also affects how seriously adversaries regard American hard power.

Capacity covers the size of the military—how much the nation can ask service members to do without imposing the undue strain of longer and more frequent deployments. When the four service chiefs discuss the size of U.S. fleets of ships and aircraft or even brigades of soldiers, they are referring to the capacity—or supply—available to meet all current and expected future demands. Capability is about not size, but what the military can do. A modern soldier or ship has far more proficiency than its predecessors, for instance. Capabilities are often connected to technological advantage—a traditional advantage of American military power that is waning. After a procurement holiday in the 1990s and a hollow buildup during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, American military capabilities have declined independently and relative to adversaries like China, Russia, and Iran. The all-volunteer force is a group of highly qualified, educated, and trained professionals. The volunteer aspect of the fighting force attracts military personnel of the highest quality—a group of citizens who count combat as their profession. However, 15 years of constant operations, combined with ill-advised budget cuts, have created cracks in the force. Further, the military faces new challenges in finding and keeping the right talent in roles like cyber personnel and drone pilots.

Capacity

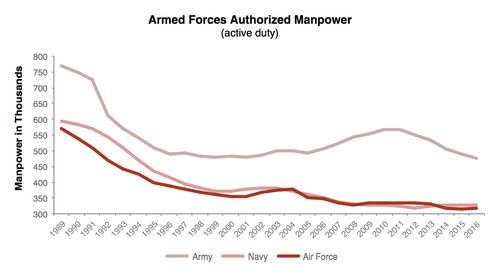

Even though the number and severity of threats to the United States continues to expand, the U.S. military is only getting smaller. In the 1990s, the U.S. prematurely dismantled the force that helped it win the Cold War. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the size of the Air Force and Navy continued to decline, while the size of the Army rose temporarily before contracting just as sharply. Only the Marine Corps, the smallest of the armed services, may remain as large as it was in the mid-1990s. Last year, the bipartisan National Defense Panel reached the conclusion that the size of the U.S. military “is inadequate given the future strategic and operational environment.”

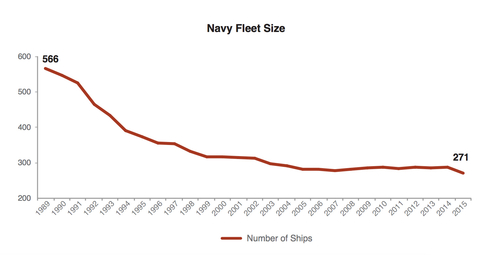

Today, the Navy battle fleet consists of roughly 280 ships, down more than 10 percent since 9/11. Whereas the National Defense Panel recommended a fleet of at least 323 ships, the actual number will fall as low as 260 if sequestration remains in effect. The panel also warned that the Army should not fall below its pre-9/11 strength of 490,000 active-duty soldiers; however, current plans forecast cutting the force down to 450,000 soldiers over the next two years, while another 30,000 would be cut if sequestration remains in effect.

As he prepared to leave office, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Raymond Odierno warned that the Army is now “dangerously close” to the point where it can no longer serve as an effective deterrent against foreign aggression. For the Air Force, the panel recommended accelerated reconstitution of the service’s core of bomber, fighter, and intelligence aircraft. At the onset of the first Gulf War, the Air Force maintained 8,510 total aircraft. Today, that number has dropped to 3,987. Some Air Force reconnaissance squadrons have been flying continuously since 1991. Their new counterparts—drone pilots—are strained to the breaking point, a small force asked to collect an ever-growing amount of intelligence.

The National Defense Panel rightly warns that the quality of military platforms is no substitute for sufficient quantity. Potential U.S. adversaries are also improving the quality of their forces, in some cases more rapidly than we are. The U.S. also plays a unique leadership role, which means it must be prepared to deter and defeat aggression across the globe, possibly in more than one theater at a time. No matter how advanced it is, no ship, plane, or soldier can be in more than one place at a time. Therefore, as the U.S. military continues to shrink, the risk of strategic failure grows.

Capability

In 2014, the bipartisan National Defense Panel warned that the “erosion of America’s military-technological advantage is accelerating.” Both during the Cold War and since the fall of the Soviet Union, the U.S. has relied on this advantage to offset the numerical superiority of its principal adversaries. Yet now, the availability of “smart” bombs, drones, and other advanced weapon systems is growing while their cost is falling. Therefore, it is not just China, but also Russia and even Iran, closing the technology gap. One of the clearest indicators of the U.S. military’s technological difficulties is the increasing age of its most important systems. Since 2001, the Pentagon has canceled dozens of major replacement programs. The exception is the F-22 stealth fighter, intended as a replacement for the venerable F-15. Despite initial plans to procure 750 F-22s, funding was available for only 187. Meanwhile, more than 450 F-15s remain in the fleet, with an average age of 27.1 years—meaning that some of the planes are older than their pilots. These older planes are already vulnerable when operating against advanced adversary aircraft and air defense systems such as the Chinese J-20 stealth fighter and the Russian S-400 surface-to-air missile system.

Similarly, the age of the country’s nuclear delivery systems has risen substantially. The average Minuteman III missile is now 34 years old, while the average age of the Navy’s Ohio-class submarines is 25. In his final days as secretary of defense, Chuck Hagel told CBS News that maintenance crews at three separate bases had to share—via FedEx—a single specialized wrench for tightening bolts on 450 Minuteman IIIs. Although the Pentagon purchased additional wrenches after discovering the problem, its emergence in the first place illustrates the perils of failing to modernize essential systems. Alongside technology, another critical component of the nation’s military capabilities is the positioning (or “posture”) of its forces around the globe.

Graph: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Fiscal Year ’16 Green Book. |

Graph: U.S. Department of the Navy |

To address threats rapidly, the military must deploy its forces forward, far from the U.S. homeland. Today, however, the percentage of forces stationed forward has almost fallen back to the lowest level of the post–Cold War era. In 2001, 118,000 US military personnel were in Europe, a reduction of more than 200,000 since the Berlin Wall came down. Today, only 65,000 remain. Not a single Army combat brigade is stationed permanently in Eastern Europe despite Russian threats and our treaty commitments to the countries of that region. To face the growing challenges there and around the globe, the U.S. military will have to invest in the technologies and posture required to preserve the peace and maintain American leadership.

Readiness

Since 2011 in particular, the Pentagon has prioritized readiness at the expense of modernization. While the tip of the spear is sharp, the bulk of the American military is not receiving sufficiently challenging or large-scale training. Without high-level joint training, the U.S. military cannot achieve the type of dominance it demonstrated during the 1991 Gulf War. Worse yet, achieving the current levels of readiness to meet global mission requirements has meant cutting investment in modernization, personnel, and new construction. Without a significant change in the budgetary environment, the services do not anticipate returning to adequate levels of readiness until the early 2020s.

In the Army, training for nearly two-thirds of the force is being curtailed to the level of squads and platoons. Put another way, our enlisted soldiers will have insufficient opportunity to train, and the majority of our company commanders and higher-ranking officers may see little or no field time while actually in command. The Air Force has repeatedly noted that its munitions stores are dangerously low, and it is straining to simply meet the limited requirements of the current air war against ISIS. The Navy compensated for its shrinking fleet with longer and more frequent deployments, which leave necessary maintenance undone. Currently, the Navy is maintaining one aircraft carrier forward, but has very limited surge capacity ready to respond to unexpected or emergency contingencies. Deployed Marine Corps units are adequately prepared, but more than half of U.S.-based Marine Corps units are reporting significant readiness shortfalls, and 19 percent of Marine aircraft remain out of commission.

The comprehensive readiness of the U.S. military remains subpar despite targeted investment since the imposition of sequestration in 2013. Readiness is a difficult military virtue to argue for because it cannot necessarily be seen; fully trained units look no different than untrained units until they are called into combat. Yet military readiness signifies more than simply being able to fight and win. Military readiness is a key determinant of the credibility of American conventional deterrence.

Health

A number of recent developments indicate that continually asking the military to do more with less is causing serious damage that has only just begun to show, particularly in the morale and retention of key service members. Wanton budget cuts have broken faith with those who serve, leaving military personnel unable to train for the jobs they signed up for. Combined with an improving economy and a decreasing percentage of Americans qualified for recruitment, the military faces the imposing challenge of finding and keeping the talent needed for 21st-century challenges.

The four military service chiefs have, in concert, been ringing the bell about the health of the all-volunteer force since a January 2015 hearing. The chiefs continue to warn that a decade of combat followed by a high pace of operations amid deep budget cuts is leaving their soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines all skeptical of continued service. A 2014 Military Times survey captured this feeling well, finding that military personnel are deeply unhappy for reasons ranging from inadequate training and compensation to poor management and distaste about two inconclusive wars. A 2014 study by Navy officer Guy Snodgrass found disturbingly low levels of retention for SEALs, naval aviators, and nuclear personnel. And as the Air Force struggles to adequately man its fighter jets while civilian airlines begin a new hiring spree, it has found hiring and keeping drone pilots uniquely difficult.

Even as the military struggles to keep its top talent, it faces the equally daunting task of replacing the talent that leaves. Most drastically, the Army announced that it might miss even its sharply reduced recruitment goals by 14 percent in 2015, further challenging a service currently forcing perfectly good soldiers to retire as a result of reduced funding. The problem goes beyond the fact that a decreasing percentage of American youth qualify for military service based on poor physical fitness, inadequate education, or mental health problems. In the next decade, the military will have to recruit far different types of personnel for challenges in cyberspace. As Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness Brad Carson has noted, the military is failing to recruit the “quantity or quality” of cyber operators since civilian-sector opportunities are often much more attractive. The American all-volunteer force has been exceedingly successful in defending the nation and deterring would-be adversaries. But the health of the all-volunteer force is not static, nor is it a given. Without changes in personnel management, real compensation and health care reform, and the restoration of a functional political system in Washington, the U.S. military will find it difficult to find and keep the next generation of American service members.

Conclusion

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, American power has slowly but surely atrophied relative to the burgeoning threats that confront the United States. Seemingly attractive short-term defense cuts carried long-term costs, not only in monetary terms, but also in proliferating risk to American national interests. Military spending has fallen since 1991 by every metric—as a percentage of GDP, as a percentage of the federal budget, and in real terms—even as a declining share of the Pentagon budget funds combat-related activities.

Although the political worldviews of America’s last four presidents differed, none seriously considered abandoning America’s traditional commitments or the role the United States has played since 1945 as the chief guarantor of a rules-based liberal international order. Rather, American political leadership has consistently asked the military to do more with less. Without sufficient military credibility to deter or contain conflict, an ever-smaller American military has been sent abroad far more frequently than in the Cold War.

If the rosy assumptions about threats to American interests had proved true, none of this would matter. But the past decade has seen drastic and widespread negative developments for American interests, from the direct threat of radical Islamist terrorism to China’s unwillingness to cooperate instead of compete, and Russia’s delusions of grandeur. These threats to stability might each be soluble in isolation, but together they require sustained application of American economic, diplomatic, and cultural power, each buttressed by credible U.S. military power.

If American political leadership continues to underfund and overuse the military, it will not result in a less ambitious foreign policy. It will result only in greater risk to American national interests. A weaker military has resulted in less credible American security guarantees and increased likelihood of conflict. A strong American military will rebuild the trust of our allies and ensure stability for a new American century.

Mackenzie Eaglen is Resident Fellow at the Marilyn Ware Center for Security Studies at the American Enterprise Institute. David Adesnik is Policy Director at the Foreign Policy Initiative. This article was published previously by The American Enterprise Institute.