Event Date: July 29, 2020

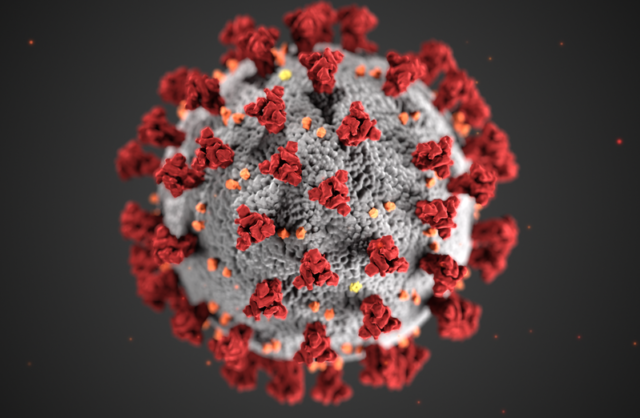

The coronavirus that caused the global COVID-19 pandemic very likely originated in a Chinese government biological weapons research laboratory. Shoshana Bryen, senior director of the Jewish Policy Center, and Charles “Sam” Faddis, a former Central Intelligence Agency operations director, agreed that though probably unintentional, the virus’ escape from the lab has revealed a great deal about the United States to its enemies.

“The Chinese have found they have the same holes” in their preparations to curb pandemic diseases as the United States, Bryen said. Hence their attempts to accelerate vaccine development by intellectual property theft.

She noted that a U.S. National Institutes of Health review this year of thousands of research grants—all made under the proviso that recipients had “no foreign involvement”—found “399 scientists of possible concern.” Of them, 133 had received “undisclosed payments” from China. Research contracts worth $154 million in 27 states were examined.

“Even for people working legally with China,” Bryen said, “the price of that collaboration is the surrender of your intellectual property.”

Bryen noted that countering the Soviet Union during the Cold War was easier than dealing with China, not to mention dispersed and multiple potential threats from biological warfare in general. “It used to be that our enemy had nuclear weapons and we had time to plan what we would do” to deter them. Today a potential threat, exemplified by COVID-19, “is everywhere—at the store, the airport” or any place people gather.

The Soviet threat was clearly recognizable, Bryen said. But the United States spent decades describing China “as ‘not as bad’, not adversarial.”

China’s initial secrecy when the coronavirus struck late last year and tardiness in sharing information contributed to the disease becoming a pandemic. This imposed heavy costs, medical and economic, on many other countries, including America, Bryen and Faddis agreed.

Hold China Accountable

Bryen said a special international committee, perhaps located in the World Health Organization or, given WHO politicization by China and its apologists, a band of democracies, should hold Beijing accountable. Such allies could include Taiwan, which was relatively successful in curbing the virus. “I’m not a big fan of the International Court of Justice,” she added, “but we might want to band together with allies” and take Beijing before the court.

Meanwhile, stronger security for research labs, suspension of cooperation with China on studies of Class A biological agents and cancellation of visas for Chinese scientists ought to be implemented, Bryen said. The United States should reinforce its military position in the Pacific, including increasing, not reducing as announced, the bomber force stationed on Guam.

Strengthening the U.S. military position vis-à-vis China in the Pacific also would include providing air defense systems for Taiwan and persuading Japan to reverse its rejection of such systems. Australia—compelled to reexamine close commercial relations with the Chinese—could be “a huge ally for us” in this regard, and even Vietnam “has been trying very hard to be on our side on this,” Bryen said.

According to Faddis, whose CIA work centered on counter-intelligence, “scientists … worldwide aren’t suspicious of everyone on an intelligence or counter-intelligence” perspective. They tend to see colleagues from other countries involved in research “for the pursuit of knowledge” at the same time “their work is being stolen from laptops” and, in the case of China, being reported to Beijing.

A Chinese researcher abroad might detest the Communist Party dictatorship, but through pressure on his family back home or other means, “he’s been made an offer he can’t refuse,” Faddis said. So, though a Chinese scientist overseas might not be a trained espionage agent, he or she will be expected to gather information, whether public or proprietary, by legal or illegal means.

Though the NIH study was admirable, not enough is being done even now by other U.S. agencies, including the Defense Department, to oversee research done by Chinese in the United States or by Americans in China, Bryen asserted.

She and Faddis agreed that if the regime of Chinese President Xi Jinping meant to use the pandemic to judge a biological warfare impact on the U.S. military, it failed. Despite the temporary withdrawal of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Roosevelt and destroyer U.S.S. Kidd from sea duty due to coronavirus infections among sailors, the Navy remained operational. Bryen said that even among National Guard members active in pandemic-related testing, the disease did not spread extensively or virulently among the military, perhaps due to the relatively young ages of service members.

Danger of Misjudgment

But China, Russia, Iran, N. Korea, and assorted terrorist movements might have judged COVID-19’s geo-political impact differently. “When the United States turns inward” and focuses on the pandemic, the economic contraction it caused and the coming presidential election, it “does not have enough bandwidth for foreign policy,” Bryen said.

“Enemies realize this and take advantage,” she added. Hence China’s persecution of its largely Muslim Uyghur population, aggression in the South China Sea “and now harassing Japan.” To which moderator Christopher Holden of the Center for Security Policy added China’s recent clashes with India, including one that left dozens of soldiers dead along the disputed Himalayan border.

Given that “biological threats have been at the top of our intelligence targets for years,” Faddis said, U.S. spy agencies failed to provide forewarning of the coronavirus spread in Wuhan. The danger should have been confirmed at the time and from multiple sources, he asserted. Though many good people are working in the intelligence services, “the job wasn’t getting done.”

When it comes to biological weapons, Faddis said, “there are no terrorist groups to my knowledge that do not have an interest in acquiring and using” them. Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State did and “when I was running CIA efforts against terrorists’ efforts” to acquire biological and chemical weapons, not a day passed without evidence of some attempt turning up. Their efforts may be relatively primitive, he noted, but sophisticated programs might not be necessary.

Al-Qaeda did have a complete biological weapons lab in Pakistan, Faddis noted. It aimed to weaponize anthrax.

But terrorists could learn from the COVID-19 pandemic that “there are many organisms capable of causing disruption.” Some are “easy to steal” and sophisticated distribution systems are unnecessary. “Just send infected people on airplanes.”

Terrorists or nation-state enemies analyzing the U.S. reaction to COVID-19 might conclude the country was slow to respond and beset with bureaucratic and political infighting, according to Faddis. If a terrorist group or hostile country obtained a biological agent that spread as rapidly as the COVID-19 coronavirus but was more lethal among people of military age and dispatched even a few infected persons to spread it, then waited until a pandemic raged to claim responsibility, even greater damage could be inflicted.

Terrorists interested in biological weapons “don’t need sophisticated equipment,” Faddis noted. “They can do it in an apartment with material you can buy on Amazon.”

Or, Bryen said, recalling plagues opposing side inflicted on each other in ancient Greece, without online purchases. Rotten food or infected dead animals worked before.

Faddis and Bryen, the latter with her husband Stephen Bryen, a former deputy undersecretary of defense, authored chapters in the Center for Security Policy’s new book, Defending Against Biological Threats: What We can Learn from the Coronavirus Pandemic to Enhance U.S. Defenses Against Pandemics and Biological Weapons.