September 1, 2021, marked the official start of operations at Haifa Bayport by SIPG Bayport Terminal, registered in Israel and owned by the Chinese company Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG). The occasion, described by the CEO of the Israel Port Authority as “a historic event unmatched in several decades,” was celebrated with a modest ceremony under COVID-19 restrictions. In recent years, the port has become a symbol of American displeasure and concern to some in Israel over Chinese investments in the country. Supporters of the venture highlight its contribution to the Israeli economy, while opponents emphasize the security risks inherent in a port operated by a company from China, claiming that the security authorities have not examined these risks in depth. The official opening of the port is an opportunity to revisit the issue.

The report by the Trajtenberg Committee on the cost of living and competition in Israel (2011) stated that the productivity of work teams at Israeli ports handling containers was 15-25 percent lower than that of their competitors elsewhere in the Mediterranean, and that this inefficiency imposes on foreign traders, and subsequently on the Israeli consumer, unnecessary annual costs of hundreds of millions of shekels. The report also stated that the main failure in the industry was the lack of competition, as labor unions had a decisive impact on the ports’ operations. In December 2011, the Israeli government adopted the Committee’s conclusions and instructed various ministries to accelerate the ports reform that was announced back in 2005. Its goals: open Israeli ports to competition, increase government revenues, and reduce the cost of living.

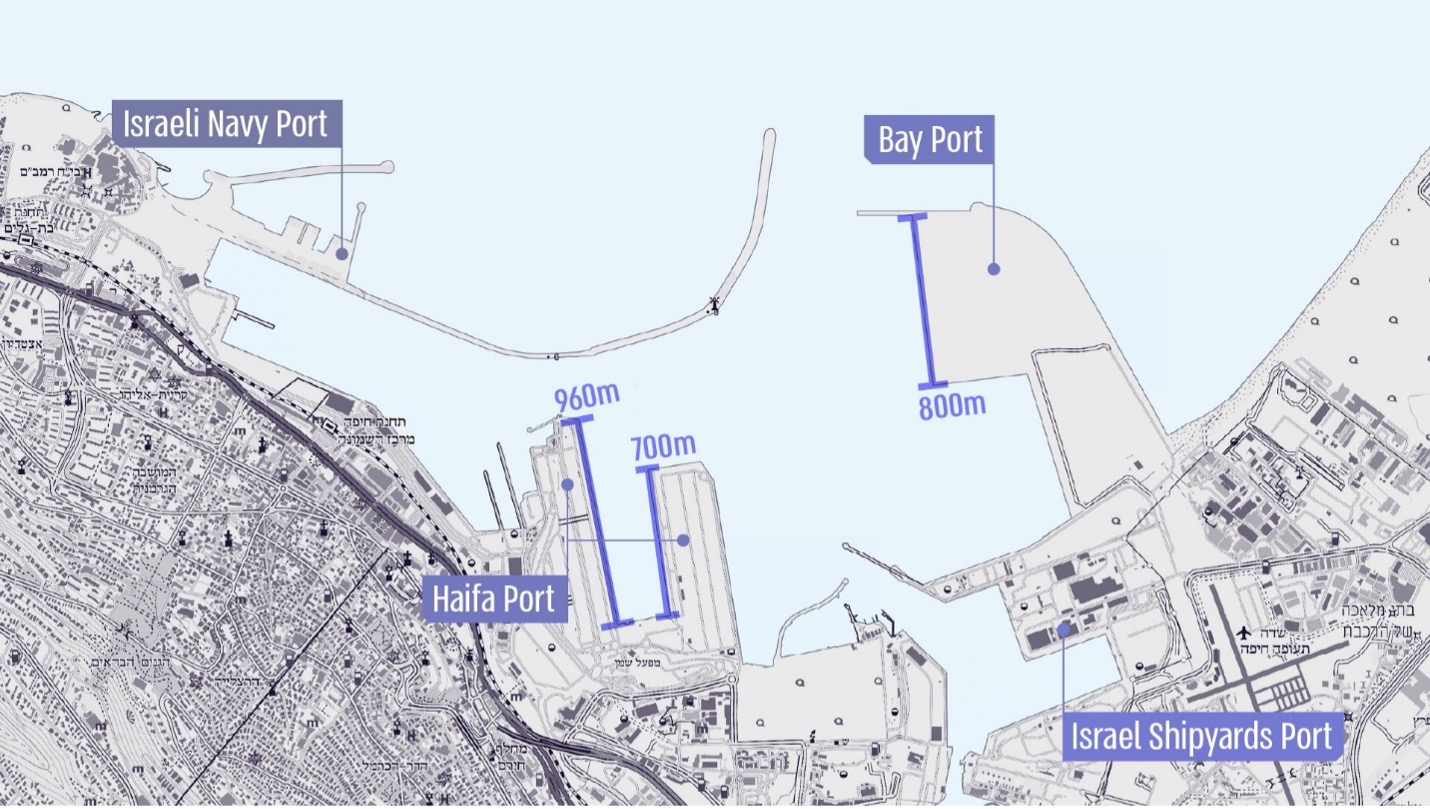

Until now, 99 percent of Israel’s trade passed through 7210 meters of quays in its seaports, including 2610 meters of container quays. In addition to the inefficiency of work teams, Israel’s outdated seaports lack adequate container capacity, as they are unsuitable for huge container ships. Haifa Port, for example, can handle ships carrying up to about 15,000 TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit, the standard unit of measurement for a 20-foot container with about 15.8 meters draught), whereas containers from Asia usually arrive in ships carrying up to 24,000 TEU and needing a draught of 17.3 meters. For a container to reach Israel, therefore, it must go through transshipment at a more advanced Mediterranean port, where the cargo is moved from a large ship to a smaller ship that is able to anchor in Israel. Alternatively, some of the cargo is unloaded in another port, to reduce its weight and enable it to anchor in the relatively shallow waters in Israel’s ports. All this lengthens the time for containers to reach Israel and increases costs, given the extra shipping time and double unloading and loading costs. According to a report from the Shipping & Ports Administration, in 2020 Israel transshipped about 100,000 TEU at a cost of $30 million. In addition, the two existing ports in Ashdod and Haifa are close to full capacity for containers, while the entry of containers into Israel is expected to grow annually by 3-4 percent.

The Importance of the New Ports

In response to these problems, the Israeli government decided to construct two new ports, near Haifa and Ashdod, or more specifically, two new private container terminals, each 800 meters long and 17.3 meters deep, able to receive the huge 400-meter long container ships carrying up to 24,000 TEU. These terminals, named Bayport and Southport, will operate alongside the two existing government ports. As part of the development plan, the quays in the existing ports will also be upgraded to enable them to compete with the new sites. The reform’s expected results will be extension of the container quays in Israel, significant upgrade of loading and unloading capacity of the seaports, and conversion from transshipment-dependent ports to ports that can themselves transship for other Mediterranean ports. In addition to reducing Israel’s dependence on foreign ports, the new construction can yield additional direct revenue as well as savings in time and costs for the entry of goods.

Today, Haifa and Ashdod ports handle about 3 million TEU per annum, with each receiving about half of the container ships entering Israel. With the opening of the new ports, whose capacity is expected to increase gradually, the existing ports will have a looser hold over the flow of containers into Israel. According to estimates generally accepted in the shipping industry, each of the new ports will be able to handle about 2 million TEU at maximum capacity. According to some media reports, the possibility of allowing the new ports to handle general cargo as well as containers is also under consideration.

In economic terms, the operation of the two new ports is essential for solving the problems at Israel’s ports. It will increase competition in the industry, reduce the need for container transshipment, save costs, and encourage greater efficiency in the existing ports.

National Security Considerations

Beyond the economic benefits, the media and various forums have raised concerns about Bayport’s management by a Chinese state-owned company. Primarily:

The company is subject to an authoritarian regime, which uses “debt traps” and takes control over assets, such as Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka and Piraeus Port in Greece.

The Chinese company could allow China’s military vessels to anchor in Israel as part of its “Military-Civil Fusion” strategy.

SIPG might disrupt the Port’s activity in times of emergency or leverage its economic power for China’s political influence over Israel.

The port might be used for espionage and cyber operations, including against U.S. Navy ships.

Even if the port does not embody special risks or create significant Israeli dependency on China, in the eyes of the United States, and certainly in Pentagon and U.S. Navy circles, it has become a provocative symbol of treacherous cooperation by a close ally, Israel, with America’s arch-rival, China, and therefore also a threat to the special relationship between the United States and Israel.

The severe arguments and their recurring resonance mandate confirmation of the facts. SIPG is indeed a Chinese government-controlled company, yet contrary to the allegations regarding Piraeus and Hambantota (some of which are contested), the Bayport is not controlled or owned by SIPG, and no debt is involved, since it did not lend money to Israel. The port operator is a private Israeli company, indeed owned by a Chinese company, yet most of its employees are Israelis, apart from a few Chinese management staff.

As for concerns about disruption to port activity during emergencies or exertion of pressure on the Israeli government, the probability and severity of these risks appear to be limited: Bayport will not be owned by its operator; it is subject to Israeli law; and in emergencies must operate according to the instructions of the Israeli security authorities, just like Israel’s other ports. If the operator does not comply with these terms, it risks committing a breach of contract and the Government of Israel will be fully entitled to replace it, admittedly in spite of the challenge involved when dealing with a large company from a global power. In addition, the increased competition between the new and upgraded ports is likely to limit the pressure on the government from both strong unions and any foreign company, while also reducing Israel’s dependence on foreign ports in Turkey and Egypt for transshipment needs.

As for espionage risks, for purposes of line-of-sight observation and reception, the Bayport Terminal is no nearer to the Israeli naval base than many civilian buildings in Haifa, although its location on the water line does indeed offer the potential for gathering acoustic intelligence (signatures of vessels and especially submarines), a potential that exists in principle in transiting commercial vessels as well. The port’s eight cranes, made by the Chinese company ZPMC, are technology-rich machines equipped with sensors and communications, raising concerns that they could be used for espionage. According to the ZPMC website, the company manufactures 70 percent of the ship to shore (STS) cranes in the world, including those in the Middle East, Europe, and the United States. This year, for example, the company’s cranes were purchased by ports in San Francisco and South Carolina. On this matter, Israel’s security authorities should learn from other countries’ experience in risk management, starting with the United States.

Bayport, like any strategic infrastructure close to Israel’s critical security assets, requires full and professional risk management. Limiting exposure to potential risks in the areas of security, espionage, and cyber stemming from the operation of ports by foreign companies is the responsibility of the relevant security entities: the Israel Security Agency (Shin Bet), the National Cyber Directorate, the Ministry of Defense, and the Ministry of Transport’s Security Department, each in its own field. The National Security Staff should integrate all agencies involved and ensure a full and seamless long-term security response for all the relevant facilities.

Relations with the United States

Under the reasonable assumption that the direct risks potentially arising from Bayport’s operation can be handled prudently and responsibly by Israel’s security authorities, the most significant challenge still remains, namely, the implications for relations with the United States.

On his recent visit to Israel, CIA Director William Burns reportedly shared with Prime Minister Naftali Bennett American concerns over Chinese penetration of the Israeli economy, particularly in areas of high tech and large infrastructure projects. Before the Prime Minister’s visit to the United States, senior Israeli officials said that Bennett would present to President Joe Biden and other senior members of the U.S. administration a new Israeli policy, defining relations with China as an issue of national security while paying closer attention to American concerns than during Netanyahu’s term.

According to reports, the subject of China never came up in meetings between President Biden and Prime Minister Bennett, but lower ranks are engaged on the issue. The visit in general aimed to “reset” relations, building trust, and working on tensions and disputes between the governments through quiet communication rather than in the media. It is therefore correct that the subject of Bayport and its associated concerns be handled as planned in a similar professional format and in this spirit, by the National Security Staff in the Prime Minister’s Office and in the National Security Council in the White House. Mutually coordinated risk management and updates will help restore the subject to its proper dimensions, and hopefully to media coverage that is factual, professional, and proportionate.

Conclusion

Haifa’s Bayport is a clear example of the emerging challenges in Israel’s changing strategic environment. What began with clear national needs was answered by maximizing opportunities in the global economy and the advantages of international corporations, including from China. Since the contract for the Bayport terminal was signed in 2015, a strategic “climate change” has unfolded, with Washington’s official declaration in 2017 of the era of Great Power Competition, centering on economic, technological, and strategic rivalry with Beijing.

While the port operation begins when the new era is already well underway, a considerable part of the criticism derives from judging past decisions according to present conditions, and from echoing unexamined claims. Prudent policy should learn from past lessons and must focus not on hindsight but on the present and the future, and on the quality of decisions affecting projects currently on the agenda, finding the correct balance between economic needs and security needs. Israel must continue to work on strengthening its special strategic relations with the United States, while at the same time promoting fruitful and safe economic relations with China.

BG (res.) Assaf Orion, IDF is a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in Israel and Director of its research program on Israel-China. He is also an international fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Galia Lavi is a Research Fellow and the coordinator of the Israel-China program at INSS. She is also a Ph.D. student at Tel Aviv University. A version of this article was published by INSS in September.