Former President Jimmy Carter’s declining health has prompted widespread review of his one-term presidency. It was a decidedly mixed bag. Despite a conservative orientation in his cabinet, Carter pursued an accommodationist policy toward the Soviet Union, and only after the Russian invasion of Afghanistan did he begin to rebuild U.S. defense capabilities.

Three momentous international events occurred during his administration (Jan. 20, 1977 – Jan. 20, 1981): two failures and a success engendered by the determination of his partners to subvert his diplomacy. Iran, Afghanistan, and the Camp David Accords constitute his legacy.

The Shah of Iran, a longtime ally of the United States and the West, was ousted and replaced by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his radical Islamic regime in early 1979. Later that year, a group of “students” took over the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, holding 52 Americans hostage.

The single attempt by the Carter administration to mount a rescue, Operation Eagle Claw, was a miserable failure, resulting in the deaths of eight U.S. servicemen. The Iranians taunted Carter on his way out, waiting until precisely the moment that Ronald Reagan took his oath of office to release the hostages. Television coverage in the U.S. flipped from scenes of one to the other.

Forty-two years later, the Ayatollahs still run a ruthless, thuggish theocracy and have subverted half a dozen other countries while pursuing their nuclear ambitions.

In Afghanistan, U.S. Ambassador Adolph Dubs was murdered in 1979, and by the end of the year, the Soviet Union had invaded the country and ruled Kabul. The Soviets are gone now, but the 42 years since the invasion have cost thousands of American and Afghan lives and countless billions in treasure. And, at the end, the Taliban rules.

In the Middle East, Carter thought he could coordinate with the Soviet Union (before the Afghan invasion) to build a comprehensive peace between Israel, Egypt and the Palestinians. It was doomed by the partners. Egypt had only a few years before ended the military relationship with the Soviets and President Anwar Sadat was unwilling to bring them back.

Israel’s Prime Minister Menachem Begin found Carter’s plan unacceptable, first because of the presence of Moscow and second because the pre-determined result was to create a Palestinian state.

The two decided on an “end-run” that ultimately resulted in the Camp David Accords and Carter’s one true success.

On 19 Nov. 1977, Sadat flew to Israel in an unprecedented initiative to change the political and military dynamics of the region. Officially, he came at Begin’s invitation, but Egypt’s desire to come to terms with Israel actually began coalescing as early as 1974, after the October 1973 Yom Kippur War, initiated by Egypt and Syria, ended with Israeli troops 90 miles from Cairo. Not only Sadat, but his top military leader, Gen. Ahmed Badawi, were ready to end the conflict. (A then-secret meeting in the Sinai desert made Egyptian intentions known to Israel.)

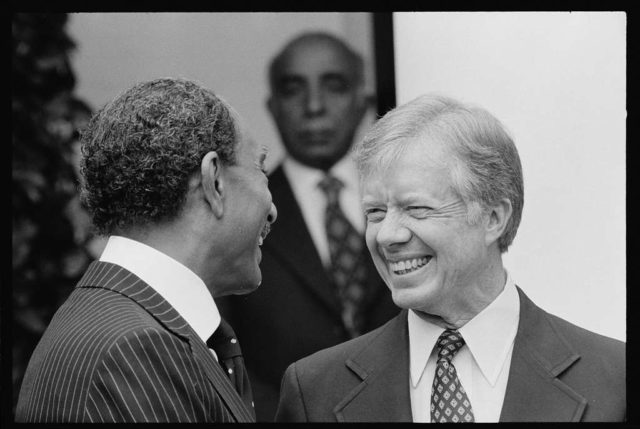

Sadat’s arrival in Israel and his address to Israel’s Knesset touched off bilateral negotiations that, unfortunately, stalled. The U.S. State Department had strongly believed that America’s absence from the process undermined U.S. influence in the region and wanted to change the dynamic. It was then that Carter rose to the occasion in his one great foreign policy victory (then seen as a significant gamble). Carter invited Begin and Sadat to Camp David. Both accepted.

The Camp David negotiations were difficult. Sadat was negotiating not only territorial and security issues, primarily the Sinai territory and delineation of boundaries, but he was also attempting to push Israel into accepting a Palestinian state. Carter was sympathetic to the Palestinians but had little chance of persuading Begin.

Begin then proposed what he called “autonomy” for the Palestinians, for which he received approval from the Knesset. In Begin’s view “autonomy” would grant the Palestinians administrative but not political control and definitely not sovereignty over the disputed West Bank and Gaza. While Gaza was not then of much importance to Israel, the West Bank – Judea and Samaria – were important for political, religious, historical, and security reasons.

Camp David resulted in two agreements, a political agreement covering the Sinai and the disposition of Egyptian and Israeli forces (with the establishment of the U.S. Sinai Field Mission, replaced in 1981 with the UN-supported Multinational Force and Observers) and an agreement and set of principles on the Palestinian question that promised autonomy for the Palestinians and laid out a process for negotiations.

Carter’s achievements at Camp David – and his (late) understanding about the need to build up American military capability – were overshadowed by his failure in Iran, and his soft-pedaling Russia’s military buildup, nuclear challenge and invasion of Afghanistan. It was left Ronald Reagan to rebuild the American military and face down the Russians.

But almost 43 years later, Israel and Egypt have not only maintained, but strengthened their relationship. The two governments have worked together to control ISIS- and Iranian-sponsored terrorism in the Sinai, and with the advent of the Abraham Accords, have enhanced their political and economic ties.

Jimmy Carter deserves a great deal of credit in getting the two sides to reach agreement and promoting the implementation of the Camp David Accords that followed.