While a few statements and photo ops here and there might suggest that Saudi Crown Prince and de facto ruler Muhammad Bin Salman (MBS) is in the process of replacing Saudi Arabia’s traditional partner, America, with China, a look at trade numbers and bilateral investments show that Riyadh has not made of China, Iran, or Russia serious economic partners, let alone in defense and diplomacy. Beijing’s non-liberal, non-democratic, non-interventionist world order does appeal to Riyadh, which might be hedging, but so far, the Saudis seem to be sticking to their traditional proximity to America and the West.

Surprise Diplomacy

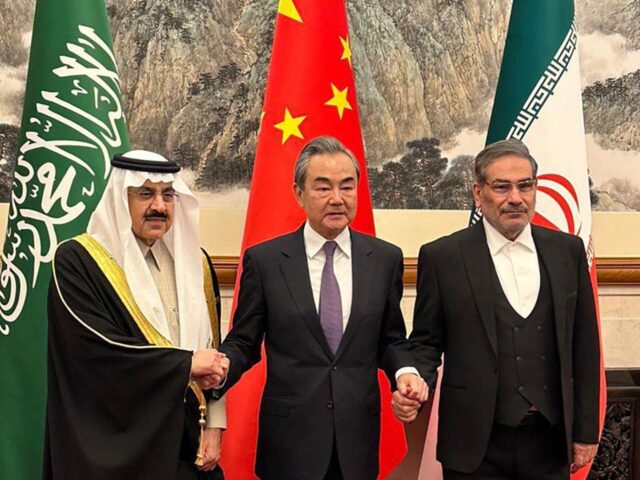

On March 11, MBS pulled a surprise. In Beijing, the foreign ministers of Saudi Arabia and Iran met and announced the restoration of diplomatic ties, seven years after Saudi Arabia had severed them in the aftermath of an Iranian mob setting the Saudi embassy in Tehran on fire.

In global relations, surprise seems to be MBS’s thing. On June 5, 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Egypt suddenly cut ties with Qatar and demanded that Doha live up to its promise and end its sponsorship of Islamist organizations. MBS apparently had an even bigger surprise in mind. It fortunately did not materialize. According to late Kuwaiti Emir Sheikh Sabah al-Sabah, Kuwait managed to convince Riyadh to stop “any military action” against Qatar.

Four years later, Qatar was still in bed with Islamists when, again suddenly, MBS was seen on January 5, 2021, driving around with Qatari Emir Tamim Bin Hamad in the historic Saudi town of al-Ula. MBS had apparently turned the page. His disagreement with Qatar was now water under the bridge.

With Iran, MBS’s restoration of ties took longer and came only after the war in Yemen had reached a stalemate and after the warring parties had settled for an open-ended truce.

Civil war in Yemen broke out in 2014 when the pro-Tehran Houthi militia toppled the internationally recognized government in Sanaa. Fearing that the Houthis would take hold of the Yemeni army’s stock of ballistic missiles, mainly old Soviet Scuds, MBS convinced fellow Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—the UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman—to intervene to disarm the Houthis and restore the Yemeni government. Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar offered token support, leaving Saudi Arabia and the UAE to do the heavy military lifting.

War in Yemen dragged on longer than MBS and the UAE had anticipated. When the Houthis depleted their Scud stockpile, they replaced it with explosive drones and missiles from Iran and continued to attack civilian targets—mainly Saudi and Emirati airports and oil facilities. Starting in 2019, with US assistance, both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi had brought online air defense systems that managed to shoot down at least half the Houthi drones and missiles, substantially eroding the potency of this Yemeni-Iranian weapon.

In late 2021, the Houthis decided to push eastward to expand the borders of the pocket that they control in Yemen. They attacked government-held territory that is home to Yemen’s modest energy reserves. At its peak in 2010, Yemen produced 30 million barrels of oil a year, collecting an annual revenue of $2 billion that dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh used, before being toppled, to fund his state, entourage, and security agencies. To put the Yemeni oil number in context, consider that Saudi Arabia produces nine million barrels a day.

The Houthi offensive seemed to be winning ground and beating Saudi-supported government forces. The UAE came to the rescue and instructed its well-armed and well-trained militia, al-Amaleeq, (Arabic for “giants”) to check the Houthi advance. Al-Amaleeq gave the Houthis a beating and forced them to retreat to their pocket. In revenge, the Houthis hit the UAE with explosive drones, most of which were intercepted before they reached targeted oil facilities. A few months later, on April 22, 2022, the Houthis accepted a six-month truce that was renewed indefinitely.

During the early weeks and months that followed the attack on Saudi diplomatic missions, in January 2016, former Iranian President Hassan Rouhani refused to apologize to Riyadh. But by summer of 2016, Iran was sending clear messages of regret. In November, an Iranian court held 20 people responsible for the attack on the Saudi embassy. Rouhani demanded that the perpetrators be punished.

As Iran signaled its willingness to move on, Saudi Arabia dug in its heels until, in April 2021, an Iranian delegation arrived in Baghdad and asked former Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi to mediate with the Saudis. Kadhimi landed in Riyadh and met with MBS. Less than two weeks later, the delegations of Saudi Arabia and Iran held the first of five dialogue sessions, all in Baghdad.

In April 2022, Yemen’s truce went into effect. It was then that MBS capitalized on Iraqi mediation, which birthed the Beijing deal 11 months later. MBS was only waiting for the right time to declare his surprise restoration of ties with Iran.

The opportunity arose when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia in December. Xi had many requests for the Saudis, first and foremost to denominate $90 billion of bilateral trade in Chinese yuan instead of the US dollar. Saudi Arabia promised to look into the matter.

Next, the Chinese president discussed Gulf security issues. The Saudis voiced concern over Iranian belligerence, both directly as in the Iranian attack on the Abqaiq Saudi oil facility, in September 2019, and indirectly through Houthi proxies. Saudi Arabia sells China 1.75 million barrels of oil per day, or 20 percent of its output and 15 percent of Chinese crude imports. Given the volume of China’s oil imports from Saudi Arabia, Beijing’s interests are best served in a secure Gulf and flowing energy. Iranian attacks on Saudi oil facilities, whether direct or through Yemeni proxies, hurt those interests.

Reports have it that the Chinese president promised to make Iran commit to Saudi Arabia’s airspace security. Tehran had signed, in March 2021, a 25-year deal in which Beijing promised to invest $400 billion in the Iranian economy in return for discounted Iranian energy. Iran’s increased economic dependence on China gave Beijing enough leverage to extract an Iranian promise to stop threatening Gulf and Saudi security.

US Looks at the Deal

As both Riyadh and Tehran enshrouded their agreement with ambiguity, their Beijing pact has raised eyebrows in Washington, with many fearing that Riyadh was changing sides and giving America’s rival, China, an advantage in the Gulf region.

In fact, Iranian media went as far as declaring a new security architecture in the Gulf and the birth of a new multipolar world order to replace the current unipolar American-led order. Iranian media reported that Saudi Arabia had applied for membership with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, an anti-Western outfit whose membership includes China, Russia, and India. Iran maintains observer status while Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Egypt, and Turkey are all dialogue partners.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE seem to have been playing along, pretending to be switching from America’s unipolar world to China and Russia’s multipolar one. In June, foreign ministers of the two Gulf nations visited South Africa to participate in a BRICS conference. That organization consists of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa and is another one of those international organizations that advocate a multipolar world order to replace the current Western-dominated one.

But are the Saudis Moving?

But for all the statements and photo ops, nothing on the ground suggests that any GCC country is about to abandon its partnership with the US-led coalition and join the Chinese-Russian axis, of which Iran is a junior member.

Despite all China’s pleas, Saudi Arabia has yet to denominate its bilateral trade with China in yuan. Meanwhile, bilateral Saudi-Chinese trade seems to be the only economic link between the two countries. Saudi investments in China remain below $5 billion, compared to close to $40 billion in the US. Similarly, Chinese investments in Saudi Arabia are still puny, at about half a billion dollars. For comparison, consider American Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Saudi Arabia that stands at $11 billion.

The Saudi Arabian economy was designed along the lines of Western economies. Riyadh has gone to great lengths to eradicate corruption, especially since MBS’s accession to power in 2015. Chinese investments in the Middle East have a bad reputation. Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (SOE) often inflate prices and share kickbacks with local officials. Iraq has been infested with such corrupt deals.

Riyadh, for its part, has been aware of the Chinese business culture of corruption, and has thus minimized its exposure to Chinese FDI, which are small in Saudi Arabia compared to the rest of the region and the world.

With little mutual investment between Riyadh and Beijing, and as the Saudis rebuff Chinese requests to partially dump the US dollar, jumping to the conclusion that the Beijing agreement with Iran shows that Saudi Arabia is distancing itself from Washington and getting closer to Beijing is premature.

Similarly, dollar figures of trade between Saudi Arabia and Iran have yet to indicate that Riyadh is undermining the position of a US-led coalition against Iran’s destabilizing behavior in the region, including Tehran’s sponsorship of terrorism and pursuit of nuclear weapons.

Bilateral trade between Saudi Arabia and Iran has been historically low. Before 2016, trade between the two countries was negligible at $14 million. Since the Beijing Agreement was signed in March, Riyadh has imported worth $15 million of steel ingots and grapes from Iran. Neither item is on the US list of sanctions.

And because Washington imposes sanctions on Iran’s shipping and naval insurance sectors, Iranian merchandise was shuttled to Saudi Arabia in trucks traveling through Iraq.

American sanctions on Iran also make it hard for exporters to collect their money through Iranian banks, whose links to the global SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) system are currently frozen. Instead, Iranian merchants can either collect their money in cash, or open accounts in Saudi banks. And while Iranian Minister of Economic Affairs Ehsan Khandouzi said he expected bilateral trade with Saudi Arabia to hit the $1 billion mark, such a number seems to be too ambitious.

Since patching things up with Qatar in 2021, MBS has gone on a blitz of zeroing out foreign policy trouble. Observers believe that such policy is a prerequisite for switching the Saudi economy’s reliance on oil rent to knowledge and services.

As MBS de-escalates conflicts on all fronts, friends and foes have tried to guess whether his new policy is a prelude to switching sides, from the US-led camp to the multipolar order imagined by Russia, China, and Iran. And while a few statements here and there might show that the Saudi crown prince is indeed preparing to change partners, a look at trade numbers and bilateral investments suggest that Riyadh has not made of China, Iran, or Russia serious economic partners, let alone in defense and diplomacy.

For the foreseeable future, Saudi Arabia and Gulf countries seem to be staying in the US camp, and there is little to show otherwise, despite all the noise and photo ops.

Hussain Abdul-Hussain is a research fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD). Follow Hussain on Twitter @hahussain.